by Jilly Cooper

On cue, Simon Harris’s two hyperactive monsters roared past, sending an aspidistra flying. Ten seconds later they were followed by Simon Harris, with Coronation chicken all over his beard. The baby in the sling was bawling its head off.

‘Did they go this way?’ asked Simon frantically.

There was a crash from the drawing-room.

‘I’m afraid so,’ said Rupert.

Maud wrinkled her nose as he rushed out.

‘That baby needs changing.’

Rupert laughed. ‘All his children do. I’d take the lot back to Harrods if I was him.’

Rushing almost as fast in the opposite direction came Paul Stratton searching for Sarah, who was sitting on a wall giggling with Bas.

‘Paul’s jeans appear to be castrating him even more than his new wife,’ said Rupert, forking up chicken at great speed. ‘If he bends over, his eyes will pop out.’

Maud admired the length of Rupert’s pale-brown corduroyed thighs. After four large glasses of wine, she suddenly had an irresistible urge to touch one of them.

‘She’s beautiful, his wife,’ said Maud.

‘She’s a tramp,’ said Rupert, ‘and Paul’s living in Cloud Cuckold Land.’

‘What’s Bas like?’ asked Maud, putting her chicken down on the floor untouched.

‘Divine,’ said Rupert. ‘One of my best mates. Runs a phenomenally successful wine bar, dabbles in property, hunts four days a week in winter, plays polo all summer, and screws all the prettiest girls in four counties. Can’t be bad.’

‘He doesn’t look like Tony,’ said Maud.

‘They had different fathers. After twenty-three years of utter fidelity to Lord Pop-Pop, Tony’s mother fell for an Argentinian polo player. The result to everyone’s amazement was Bas. Hence the name of the wine bar – the Bar Sinister.’

Maud laughed. Many men had told her that her laugh was beautiful – low, musical, joyous.

‘Tell me about your children,’ said Rupert, who’d finished his chicken.

‘I’ve got a son, Patrick.’

‘I’m not interested in him.’

‘And a daughter of just eighteen.’ Seeing Rupert’s eyes gleam, Maud added hastily, ‘But she’s shy and retiring; doesn’t go out much. And one of fourteen, who’s madly in love with you; she’s kept her binoculars trained on your house ever since we arrived.’

‘That’s nice. They’re adorable at that age.’

‘She’s got a brace on her teeth, and going through a very plain stage,’ said Maud even more hastily. ‘Tell me about Freddie Jones.’

‘He’s a saint.’

‘Because he buys your horses?’

‘Not entirely. I’ve offered Declan a horse if ever he wants a day’s hunting.’

‘Declan rides very well,’ said Maud. ‘He grew up on a farm. Who’s that little woman who’s bending his ear at the moment, who keeps making silly faces? He looks as though he needs rescuing.’

Rupert glanced round. ‘Not by me, he doesn’t. That’s Freddie’s wife, Valerie, the Lady of the Mannerism; won’t rest till she’s Queen of England. Freddie unfortunately thinks she is already. Keeping down with the Joneses is an eternal problem round here.’

‘You’re very black and white, aren’t you?’ said Maud, noticing his long fingers and wishing they were unbuttoning her silk dress.

‘I like people or I don’t.’

Looking up, Maud gave Rupert the benefit of her most bewitching smile. The great expanse of white eyeball and the beautiful teeth (unfairly even and white after so few visits to the dentist) really did light up her face. At the same time her hair escaped from its jewelled comb and cascaded down her back.

‘I hope you like me,’ she murmured.

‘I don’t know yet,’ said Rupert slowly, looking at her mouth and then her breasts. ‘I like your husband very much, but you’re certainly too disturbing to be living across the valley.’

Glancing through the conservatory window at Maud’s pale, rapt face, Declan thought she looked far more exotic than any of Monica’s orchids and felt a sick churning jealousy. Rupert had his back turned. Maud was weaving her spells again.

‘You need but lift a pearl-pale hand,’ Declan quoted to himself despairingly, ‘And bind up your long hair and sigh, And all men’s hearts must burn and beat.’

Oh Christ, if only he could get away from this party, and spend a few hours on his Yeats book. And in three days he’d got to interview Johnny. He’d done his duty at this party. He’d talked to the appallingly pompous Paul Stratton, and asked Simon Harris about his wife, and answered questions from fearful bone-headed locals about the famous people he’d interviewed, and listened to at least three women who had daughters reading English at University, who wanted to go into television, and now he was trapped by this monstrous dwarf.

‘It’s so wonderful to be able to stand at the bottom of one’s drive,’ said Valerie Jones, ‘and not be able to see one’s house.’

She was wearing a cricket sweater and white flannels, and rabbited relentlessly on like an obnoxious player who wouldn’t stop bowling when the umpire said Over.

‘We couldn’t be happier with Green Lawns,’ she went on smugly. ‘We looked at The Priory, you know. It was on the market for ages, but it’s awfully cold, and I really couldn’t live in a property that didn’t get sun until the evening. I must have sunshine.’

She held her silly face up to the sun. Declan longed to clout a six into it. He could see Maud was running her hand through her hair now, shaking it out. Her body was arched towards Rupert. Unnoticed by either of them, the fatter of Monica’s labradors was busy gobbling up Maud’s chicken.

‘Even Freddie was nervous about meetin’ you,’ Valerie was saying. ‘Ay said, don’t be silly, Fred-Fred. Famous folk are just like everyone else. Most of them are on drugs, and very lonely, because all their friends have deserted them.’

‘I wish some of ours would desert us,’ said Declan grimly. ‘That’s why we moved to the country.’

In the hall Tony was throwing out Simon Harris. The elder monster had just smashed a Ming bowl.

‘Was it very old?’ stammered Simon, white-lipped.

‘Only just over six hundred years,’ hissed Tony. ‘Out, OUT.’

‘I’ll pay for it.’

‘It would take you two years’ salary, which I don’t think you’d like from the way you’re always whining about money. Now, bugger off, before those little bastards break the whole place up.’

‘I must go,’ said Rupert.

‘Oh,’ said Maud, put out. She wanted the afternoon to go on for ever. It was as though the sun had gone in.

‘I’ve got to pick up my children from my ex.’

‘How old are they?’

‘Eight and ten.’

‘You must bring them over to see us. Taggie, my daughter, dotes on children. She’d keep them out of our hair. Has your ex-wife married again?’

‘Yes,’ said Rupert getting to his feet, ‘to my old chef d’équipe, Malise Gordon. He used to manage the British team when I was show jumping. Bit of a tartar, so I feel their twin rays of disapproval if I roll up late.’

At that moment Freddie Jones rolled up with two over-loaded plates of Pavlova.

‘’ullo my darlings; brought you some sweet.’

‘Not for me, I’m off,’ said Rupert.

‘How’s my horse getting on?’ said Freddie.

‘Bloody well. I think we’ll run him in a two-mile chase at Cheltenham. He’s ready for it.’

They were interrupted by frantic tapping on the window pane. Valerie Jones was glaring in: No dessert, Fred-Fred, she mouthed.

Lizzie Vereker took Valerie’s place beside Declan: ‘D’you need rescuing?’

‘I did,’ said Declan. ‘I don’t any more. She nails your feet to the floor, but I’m trained to cut across wafflers.’ He shook his head. ‘How’s the book going?’

‘Backwards,’ said Lizzie. ‘Are you nervous about your first p

rogramme?’

‘Yes. I shouldn’t be allowed out before a series starts. I get so wound up, I can’t talk to anyone.’

‘Good luck with Johnny, ‘said Rupert, pausing on his way out.

‘Come and have dinner with us after the programme,’ said Declan.

‘Can’t. I’m off to Ireland. I know we’re both hellishly pushed, but let’s get together soon. I’ll come and look at your wood. ‘Bye, darling.’ He gave Lizzie a kiss.

As he crossed the deserted hall Sarah Stratton came out of the downstairs loo, reeking of Anaïs Anaïs. Glancing back towards the garden, Rupert saw that James was nose to nose with Paul Stratton, each mistakenly assuming he was furthering his own career.

‘Come and feed the fish,’ said Rupert, taking Sarah’s hand.

He led her down a grassy ride, flanked on either side by yew hedges, to the fish pond. Stuffed to bursting by Simon Harris’s monsters, the carp didn’t even bother to ruffle the surface of the water lilies.

‘Any repercussions?’ asked Rupert.

Sarah shook her head. ‘It seems funny, belting away from your tennis court with a pink dress over my head. The entire Gloucestershire fire brigade will recognize my bush, but not my face.’

Rupert grinned, and pulled her inside the thick curtain of a weeping ash. After he’d kissed her, he said: ‘When are we going to finish the set?’

‘Very soon, please.’

Her smooth golden face was green in the gloom; she looked like a water nymph.

‘How was Maud O’Hara?’ she asked.

‘Seemed pretty unmoored to me,’ said Rupert.

‘Looks as though she’d like to tie herself to you.’

‘Were you jealous?’

Sarah nodded.

‘Pity your husband’s summer recess coincides with mine.’

‘He’s never away,’ moaned Sarah, as Rupert’s fingers moved between her legs. ‘Why don’t we nip into the gazebo?’

‘Got to pick up the children. I’m late already.’

‘When am I going to see you?’ gasped Sarah, as Rupert’s other hand slid down underneath her pants at the back.

‘Come to Ireland with me. I’m leaving on Wednesday afternoon.’

‘I can’t. My ghastly step-children are coming for a couple of weeks on a trial visit. I know who it’s going to be a trial to as well. Paul’s going to Gatwick on Tuesday to meet them.’

‘That’ll give us at least five hours. Ring me at home the minute he leaves.’

‘Hulloo,’ called a male voice.

Frantically straightening her dress, Sarah shot out through the ash tree curtain and bent once more over the fish pond to hide her flaming face.

Wiping off her pale-pink lipstick, Rupert followed in a more leisurely fashion.

‘Sarah and I were talking about horses,’ he told an apoplectic Paul. ‘If you’re going to fork out for a groom, feed and grazing for two hunters, you’re talking about at least fifteen thousand a year. Better if Sarah kept something at my yard.’

‘We’ll discuss it in our own time, thank you,’ spluttered Paul. ‘We must go, Sarah.’

Back in the conservatory, Maud was being heavily chatted up by Bas.

‘Shove off, Bas,’ Monica told him. ‘Declan wants to go and I want two minutes with Maud.’

‘I’ll come and see you,’ said Bas, blowing Maud a kiss.

He’s very attractive, thought Maud dreamily, but not in Rupert’s class.

‘I’m sure you’re a joiner,’ said Monica, who was now busily dead-heading a pale-blue plumbago growing up a whitewashed trellis.

‘No,’ said Maud, ‘I’m an actress.’

Very firmly, but charmingly, she managed to resist all Monica’s urging that she should get herself involved in any kind of charity work.

‘The children come first,’ said Maud simply.

‘But two of them are away,’ protested Monica, ‘and Taggie’s eighteen.’

‘But still dyslexic,’ sighed Maud. ‘She needs her mother, and of course Declan needs his wife.’

‘But you must do something for charity,’ persisted Monica. ‘It’s such a good way of meeting new people, and it’s awfully easy to get bored in the country.’

‘I never get bored,’ lied Maud. ‘There’s so much to do to the house. I can’t pass a traffic light at the moment without wondering whether yellow would go with red in one of the children’s bedrooms.’

Driving home, Maud put a hand on Declan’s thigh, edging it upwards. Pixillated by Rupert’s interest, and Bas’s extravagant compliments, hazy with drink, she felt wildly desirable and alive again.

‘Let’s go straight to bed.’

‘What about Taggie?’ said Declan.

‘Say we’re both tired.’

Declan curled a hand into the front of her black dress.

‘They all wanted you.’

‘Did you like that?’ whispered Maud.

‘I know how hard I’ve got to fight to keep you,’ he said harshly and felt her nipples hardening.

Back in their bedroom at The Priory, he undressed her slowly down to her suspender belt and stockings, so black against the soft white skin.

‘When did you get those bruises?’ she said sharply, as he took off his shirt.

‘This morning. The focking mowing machine kept stopping and I didn’t.’

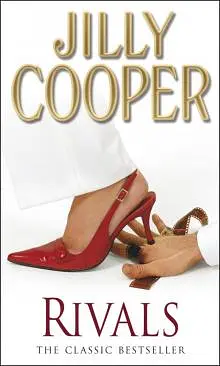

RIVALS

12

Gertrude, the mongrel, was walked off her feet in the next three days. When Maud wasn’t drifting up and down the valley in a new lilac T-shirt and matching flowing skirt, hoping to bump into Rupert, Declan was striding through the woods, trying to work out what questions he would ask Johnny Friedlander and driving Cameron Cook crackers because he was never in when she wanted to talk to him.

Cameron’s patience was further taxed by her PA getting chicken-pox, and having to be replaced by Daysee Butler, easily the prettiest girl working at Corinium but also the stupidest.

‘Why d’you spell Daisy that ludicrous way?’ snarled Cameron.

‘Because it shows up more on credits,’ said Daysee simply.

Like all PAs that autumn, Daysee wandered round clutching a clipboard and a stopwatch, wearing loose trousers tucked into sawn-off suede boots, and jerseys with pictures knitted on the front.

‘It’s just like the Tit Gallery with all these pictures floating past,’ grumbled Charles Fairburn.

Programme day dawned at The Priory with Declan roaring round the house.

‘Whatever’s the matter?’ asked Taggie in alarm.

‘I have absolutely no socks. No, don’t tell me. I’ve looked behind the tank in the hot cupboard, and in all my drawers, and in the dirty clothes basket. Utterly bloody Patrick and utterly bloody Caitlin swiped all my socks when they went back, so I have none to wear.’

‘I’ll drive into Cotchester and get you some,’ said Taggie soothingly.

‘Indeed you will not,’ said Declan. ‘I’m driving into Cotchester, and I’m buying thirty pairs of socks in such a disgossting colour that none of you will ever wish to pinch them again.’

He was very tired. He hadn’t slept, panicking Johnny might roll up stoned or not at all. And yesterday he and Cameron had been closeted together for twelve hours in the edit suite, putting together the introductory package, rowing constantly over what clips and stills they should use. Daysee Butler’s inanities hadn’t helped either. Nor had Declan’s dismissing as pretentious crap an alternative script Cameron pretended one of the researchers had written, but which she in fact had toiled over all weekend. She couldn’t run to Tony, who was in an all-day meeting in London, but got her revenge while Declan was recording his own beautifully lyrical script, by making him do bits over and over again because of imagined mispronunciations or technical faults or hangings outside. They parted at the end of the day not friends.

Having bought his socks, Declan arrived at the studios around five. A game show was underway in Studio 2; the Floor Manager was flapping his hands above his head li

ke a demented seal as a sign to the audience to applaud. Midsummer Night’s Dream had ground to a halt in Studio 1, because Cameron, dissatisfied with the rushes, had tried to impose an ‘out-of-house lighting cameraperson’ on the crew, who had promptly downed tools. The Rude Mechanicals, with no prospect of a line all day, were getting pissed in the bar.

Deferential, glad-to-be-of-use, Deirdre Kilpatrick, the researcher on ‘Cotswold Round-Up’, as dingy as Daysee Butler was radiant, was taking a famous romantic novelist to tea before being interviewed by James Vereker.

‘James will ask you your idea of the perfect romantic hero, Ashley,’ Deirdre was saying earnestly. ‘And it’d be very nice if you could say: “You are, James”, which would bring James in.’

‘I only go on TV because my agent says it sells books,’ said the romantic novelist. ‘Oooh, isn’t that Declan O’Hara? Now, he is the perfect romantic hero.’

Declan slid into his dressing-room and locked the door. A pile of good luck cards and telexes awaited him. He was particularly touched by one from his old department at the BBC saying, ‘Sock it to them.’

‘Da-glo yellow sock it to them,’ said Declan, chucking thirty pairs of socks in luminous cat-sick yellow on the bed.

There was a knock on the door. It was Wardrobe.

‘D’you want anything ironed?’

Declan peered gloomily in the mirror: ‘Only my face.’

He gave her his suit, light grey and very lightweight, as he was going to be under the hot lights for an hour. She hung up his shirt and tie, then squealed with horror at the yellow socks.

‘You can’t wear those.’

‘They won’t show,’ said Declan.

In Studio 3 two technicians were sitting in Declan’s and Johnny’s chairs, while the crew sorted out lighting and camera angles. Crispin, the set designer, whisked about in a lavender flying-suit. The set was exactly as Declan had wanted, except the Charles Rennie Mackintosh chairs had been replaced by wooden Celtic ones, with the conic back of Declan’s rising a foot above his head like a wizard’s chair: a symbol of authority and magic.