Copyright

Copyright © 1946 by Georgette Heyer

Cover and internal design © 2008 by Sourcebooks, Inc.

Cover photo © Fine Art Photographic Library

Sourcebooks and the colophon are registered trademarks of Sourcebooks, Inc.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means including information storage and retrieval systems—except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews—without permission in writing from its publisher, Sourcebooks, Inc.

The characters and events portrayed in this book are fictitious or are used fictitiously. Any similarity to real persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental and not intended by the author.

Published by Sourcebooks Casablanca, an imprint of Sourcebooks, Inc.

P.O. Box 4410, Naperville, Illinois 60567-4410

(630) 961-3900

Fax: (630) 961-2168

www.sourcebooks.com

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Heyer, Georgette.

The reluctant widow / Georgette Heyer.

p. cm.

ISBN-13: 978-1-4022-1351-9

ISBN-10: 1-4022-1351-4

I. Title.

PR6015.E795R46 2008

823’.912—dc22

2008017995

Table of Contents

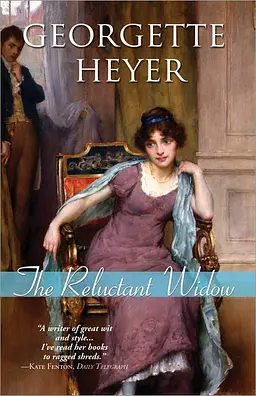

Front Cover

Copyright

One

Two

Three

Four

Five

Six

Seven

Eight

Nine

Ten

Eleven

Twelve

Thirteen

Fourteen

Fifteen

Sixteen

Seventeen

Eighteen

Nineteen

Twenty

About the Author

Back Cover

One

It was dusk when the London to Little Hampton stage-coach lurched into the village of Billingshurst, and a cold mist was beginning to creep knee-high over the dimly seen countryside. The coach drew up at an inn, and the steps were let down to enable a passenger to alight. A lady, soberly dressed in a drab-coloured pelisse and a round bonnet without a feather, descended on to the road. While she waited for a corded trunk and a valise to be extricated from the boot, the coachman, finding himself to be some minutes ahead of his time-sheet, hitched up his reins, clambered down from the box, and in defiance of the regulations governing the conduct of stage-coachmen, rolled into the tap-room in search of such stimulant as would enable him to accomplish the remainder of the journey without endangering an apparently enfeebled constitution.

The passenger, meanwhile, stood in the roadway with her trunk at her feet, and looked about her in a little uncertainty. She was expecting to be met, but as her experience had taught her that the gig was more commonly employed for the purpose of picking up the new governess than the carriage used by her employers, she hesitated to approach the only conveyance she could perceive, which was a light travelling coach, drawn up on the opposite side of the road. While she stood looking about her, however, a servant jumped down from the box, and came up to her, touching his hat, and enquiring whether she would be the young lady who had come down from London in answer to the advertisement. Upon her assenting, he made her a little bow, picked up the valise, and led the way across the road to the travelling coach. She stepped up into it, her spirits insensibly rising at this unlooked-for-attention to her comfort; and was further gratified by the servant’s spreading a rug over her knees and expressing the hope that she would not feel chilled by the evening air. The steps were put up, the door shut, the trunk bestowed on the roof, and in a very few moments the coach moved forward, bowling along in a well-sprung manner that formed a pleasing contrast to the jolting the stage-coach passenger had been enduring for several hours.

She leaned back against the squabs with a sigh of relief. The stage had been crowded, and her journey an uncomfortable one. She wondered whether she would ever become accustomed to the disagreeable economies of poverty. Since she had had every opportunity of inuring herself to these over a period of six years, it seemed unlikely. Dispirited, but determined not to give way to melancholy reflections, she turned her thoughts away from the evils of her situation, and tried instead to speculate upon the probable character of her new post.

It had been with no high hopes that she had set out from London earlier in the day. Her employer, seen once only in a quelling interview at Fenton’s Hotel, had disclosed no hint of the kindly impulse that must have caused her to send her own carriage to meet the governess. Miss Elinor Rochdale had been misled into thinking her massive bosom as hard as her rather prominent eyes, and, had any other choice offered, would have had no hesitation in declining a post in her household. But no other choice had offered. There were too often young gentlemen at a susceptible age in families requiring a governess, and Miss Rochdale was too young and too well-favoured to be eligible, in the eyes of most provident Mamas, for the position. Happily, however – for Miss Rochdale’s savings were negligible, and her pride still too great to allow of her remaining longer as the guest of her own old governess – Mrs Macclesfield’s only male offspring was a sturdy lad of seven. He was, by his mother’s account, high-spirited, and of so sensitive a temperament that the exercise of the greatest tact and persuasion was necessary to control his activities. Six years earlier, Miss Rochdale would have shrunk from the horrors so clearly in store for her, but those years had taught her that the ideal situation was rarely to be found, and that where there was no spoiled child to make the governess’s life a burden, she would in all likelihood be expected to save her employer’s purse by performing the menial tasks generally allotted to the second housemaid.

Miss Rochdale tucked the rug more closely round her legs. A thick sheepskin mat upon the floor of the coach protected her feet from the draught, and she snuggled them into it gratefully, almost able to fancy herself once more Miss Rochdale of Feldenhall, travelling in her father’s carriage to an evening party. The style of servant who had been sent to fetch her, and the elegance of the equipage, had a little surprised her: she had not supposed Mrs Macclesfield to have been in such comfortable circumstances. Upon first perceiving the coach, she had thought she had seen a crest upon the door-panel, but in the failing light it was easy to be mistaken. She fell to pondering the probable degree of gentility of the establishment ahead of her, and the various characters of its inmates, and since she was of a humorous turn of mind, soon lost herself in the weaving of several very improbable histories.

She was recalled to her surroundings by a perceptible slackening in the pace of the horses, and, looking out of the window, saw that the darkness had by this time closed in. The moon not having yet risen it was impossible to discern anything of the country through which she was being driven, but she gained the impression of a narrow and certainly tortuous lane. She did not know for how long she had been in the coach, but it seemed a considerable time. She recollected that Mrs Macclesfield had described her home at Five Mile Ash as being within a short distance of Billingshurst, and could only suppose that the way to it must be more than ordinarily circuitous. But as time went on it became apparent that either Mrs Macclesfield’s notions of distance were country ones, or she had been deliberately mendacious.

The journey began to seem unending, but just as Miss Rochdale was entertaining a suspicion that the coachman had lost his way in the darkness the horses slowed from a jog-trot to a walk, and the vehicle swung round at a sharp angle, its wheels encoun

tering an uneven gravel surface, as of a carriage-drive ill-kept. The pace was picked up again, and maintained for a few hundred yards. The coach then drew to a standstill, and the groom once more jumped down from the box.

A faint silver light had begun to illumine the scene, and as she stepped out of the coach Miss Rochdale was just able to see that the house she was about to enter was of a respectable size, although built in a rambling and rather low-pitched style. Two sharp gables, and some very tall chimney-stacks were silhouetted against the night-sky; and a lamp burning in one of the rooms showed that the windows were latticed.

The groom had tugged at the big iron bell some moments before, and the echoes of its distant clanging still sounded when the door was opened. An elderly man in shabby livery held it for Miss Rochdale to enter the house, favouring her, as she passed him, with an intent, and rather anxious scrutiny. She scarcely heeded this, for her attention was claimed by her surroundings, which were surprising enough to cause her to check on the threshold, looking about her in a good deal of bewilderment. What, her startled brain demanded, had the woman she had seen at Fenton’s Hotel to do with all this decayed grandeur?

The hall in which she found herself was a large, irregularly shaped room, with a superb oaken stairway at one end of it, and at the other a huge stone fireplace, big enough for the roasting of an ox, thought Miss Rochdale, and with a chimney which might be depended on to gush forth smoke any time some unwise person kindled a fire on the flags beneath it. The plaster ceiling, blackened between the oak beams, showed how correct was Miss Rochdale’s prosaic reflection. The stairs and the floor of the hall were alike uncarpeted, and lacked polish; long brocade curtains which had once been handsome but were now faded and in places worn threadbare, were drawn across the windows; a heavy gateleg table in the centre of the room bore, besides a film of dust, a riding-whip, a glove, a crumpled newspaper, a tarnished brass bowl possibly intended to hold flowers, but just now full of odds and ends, two pewter mugs, and a snuff-jar; a rusted suit of armour stood near the bottom of the staircase; there was a carved chest against one wall, with a welter of coats cast on the top of it; several chairs, one with a broken cane seat, and the others upholstered in rubbed leather, were scattered about; and on the walls were a number of pictures in heavy gilded frames, three moth-eaten foxes’ masks, two pairs of antlers, and a number of ancient horse-pistols and fowling-pieces.

Miss Rochdale’s astonished gaze alighted presently on the servant who had admitted her, and she found that he was regarding her with a kind of melancholy curiosity. Something in his demeanour, coupled as it was with the depressing dilapidation all around her, put her forcibly in mind of the more lurid romances to be obtained from a circulating-library. She could almost fancy herself to have been kidnapped, and was forced to summon up all her common sense to dispel the ridiculous notion.

She said, in her pleasant, musical voice: ‘I had not thought it had been so far from the coach-stop. I have arrived later than I expected.’

‘It’s all of twelve miles, miss,’ responded the retainer. ‘You’re to come this way, if you please.’

She followed him across the uneven floor to one of the doors that gave on to the hall. He opened it, but his notion of announcing her seemed to consist merely of a jerk of the head, signifying that she was to enter. After a moment’s hesitation, she did so, still more bewildered, and conscious by this time of a little feeling of trepidation.

She found herself in a library. It was quite as untidy as the hall, but a quantity of candles in tarnished wall-brackets threw a warm light over it, and a log fire burned in the grate at the far end of it. Before this fire, one hand resting on the mantelpiece, one booted foot on the fender, stood a gentleman in buckskin breeches and a mulberry coat, staring down at the leaping flames. As the door closed behind Miss Rochdale, he looked up, and across at her, in a measuring way that might have disconcerted one less accustomed to being weighed up like so much merchandize offered for sale.

He might have been any age between thirty and forty. Miss Rochdale realised that he must be her employer’s husband, and was a good deal cheered to discover that besides being a very gentlemanlike-looking man, with a well-favoured countenance and a distinct air of breeding, he was dressed with a neatness and a propriety at welcome variance with his surroundings. He had, in fact, all the appearance of a man of fashion.

He did not move to meet her, so Miss Rochdale advanced into the room, saying: ‘Good evening. The servant desired me to enter this room, but perhaps – ?’

It seemed to her that there was a faint look of surprise in his face, but he replied in a cool voice: ‘Yes, that was by my orders. Pray be seated! I trust you were not kept waiting at the coach-stop?’

‘No, indeed!’ she said, taking a chair by the table, and folding her hands over her reticule in her lap. ‘The carriage was waiting for me. I must thank you for having sent it.’

‘I should certainly doubt of there being a suitable conveyance in these stables,’ he said.

This remark, uttered as it was in an indifferent tone, seemed extremely odd to Miss Rochdale. She must have shown that she was taken aback, for he added stiffly: ‘I believe that the exact nature of the position offered to you was explained in London?’

‘I believe so,’ she returned.

‘I chose that you should be brought here directly,’ he said.

She looked startled. ‘I thought – I was under the impression – that this was my destination!’

‘It is,’ he said, rather grimly. ‘However, I do not desire that you should be under any misapprehension. I am giving you the opportunity to see with your own eyes what may not have been adequately described to you, before we come to any definite bargains.’ His level gray eyes swept the disordered room as he spoke, and then returned to their scrutiny of her countenance.

She hoped that she succeeded in preserving it. She said: ‘I do not understand you, sir. For my part, I considered myself definitely engaged when I set out from London to come here.’

He bowed slightly. ‘Oh, yes! If you still wish it!’

She could not be sure that she did, but the alternative prospect of returning to town to seek another post caused her to say cheerfully: ‘I shall do my best, sir, to fill the position satisfactorily.’ She detected irony in his steady gaze, and was disconcerted by it. She added, with a slightly heightened colour: ‘I was not aware, however, that it was you who had engaged me. I thought –’

‘It was unnecessary that you should know it,’ he said. ‘Once you have made up your mind to the bargain, I have nothing more to say in the matter.’

From what she had seen of his wife she could readily believe this; the only surprise she felt was at his having had any say at all in the matter. Yet his manner was very much that of a man accustomed to command. Feeling herself to be at a loss, she said, after a short pause: ‘Perhaps it would be as well if I were to lose no time in making the acquaintance of my charge.’

His lip curled. ‘An apt term!’ he remarked dryly. ‘By all means, but your charge is not at the moment on the premises. You shall see him presently. If what you must already have observed has not daunted you, you encourage me to hope that your resolution will not fail when you are brought face to face with him.’

‘I trust not, indeed,’ she said, with a smile. ‘I was given to understand, I own, that I might find him a trifle – a trifle high-spirited, perhaps.’

‘You have either a genius for understatement, ma’am, or the truth was not told you, if that is what you understand.’

She laughed. ‘Well, you are very frank, sir! I should not expect to be told quite all the truth, but I might collect it, reading between the lines, I fancy.’

‘You are a brave woman!’ he said.

Her amusement grew. ‘I am sure I am no such thing! I can but contrive as best I may. I dare say he has been a little spoilt?’

‘

I doubt of there being anything to spoil,’ he replied.

The coldly dispassionate tone in which he uttered this remark made her reply in equally chilly accents: ‘You do not desire me, I am persuaded, to refine too much upon your words, sir. I am very hopeful of teaching him to mind me in time.’

‘Teaching him to mind you?’ he repeated, with a strong inflexion of astonishment in his voice. ‘You will have performed something indeed if you succeed in doing so! You will have, moreover, the distinction of being the only person to whom he has attended in all his life!’

‘Surely, sir, you – ?’ she faltered.

‘Good God, no!’ he said impatiently.

‘Well – well, I must put forth my best efforts,’ she said.

‘If you mean to remain here, you would be better advised to turn your attention to the evils you can more easily remedy,’ he said, with another glance of dislike around the room.

She was nettled, and allowed herself to reply with a touch of asperity; ‘I was not informed, sir, that it was to fill the position of housekeeper that I was engaged. I am accustomed to keep my own apartment neat and clean, but I can assure you I shall not meddle in the general management of the house.’

He shrugged, and turned away from her to stir the now smouldering log with his foot. ‘You will do as seems best to you,’ he said. ‘It is no concern of mine. But rid your mind of whatever romantic notions it may cherish! Your charge, as you choose to call him, may be induced to accept you, but that is because I can force him to do so, and for no other reason. Do not flatter yourself that he will regard you with complaisance! I do not expect you to remain above a week: you need not remain as long, unless you choose to do so.’

‘Not remain above a week!’ she exclaimed. ‘He cannot be as bad as you would have me think, sir! It is absurd to speak in such a way! Pardon me, but you should not talk so!’

‘I wish you to know the truth, to have the opportunity to reconsider your decision.’

A good deal dismayed, she could only say: ‘I must do what I can. I own, I had not supposed – but I am not in a position – in a position lightly to decline –’