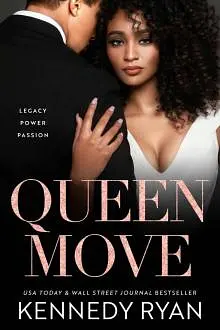

by Kennedy Ryan

“Take it from me,” Michael counters, his frown lifted, but meanness still shadowing his eyes.

“That’s the problem, right?” I ask, settling back onto my heels, no longer reaching for the yarmulke. “You think I’m going to take something from you?”

“What?” Michael’s spiteful smile slips.

“Yeah,” I say, stepping closer to him until only an inch separates our noses. “You hate that I speak Hebrew better than you do after months when you’ve been learning for years. And you hate that your sister likes me. Well, you can sleep at night because I don’t like her back.”

He pushes me hard enough that I almost fall, but I catch myself before I hit the ground. My hands slam into the concrete, palms scraping, but keeping me from landing on the sidewalk. My will and body overrule the wisdom of my mind, and I spring toward him without thinking, without weighing the odds. Three against one. I shove him back.

“This little shvartze pushed me,” Michael spits, his glare reigniting.

Shvartze.

I’ve lost count of how many times Big Boi and Dre used the N word on the Southernplayalisticadillacmuzik album blaring through my headphones, and it slid right past my ears, a stingless barb never meant to harm. But hearing it wrapped in Yiddish from these boys who have everything and want me to have nothing? It’s not the same. Coming from this boy, so proudly wearing his resentment and superiority, it’s a knife hurled right through my insecurities. It’s a slur that slices through every part of me, not just the black part.

Michael shoves me toward Robert, and Robert shoves me to Paul; they’re tossing me between each other in a game of keep-away.

Keep your head down. Keep your head down. Keep your head down.

I try my best to grab hold of my father’s warning, but my hands are raw and my ego is bruised and I’m tired of everything. Caution slips through fingers greased with rage. When Paul pushes me again, I slam my hand into Michael’s face. Blood gushes from his nose.

“Shit!” Michael cups his face, blood running between his fingers. “You’ll be sorry you did that. Hold him.”

Robert grabs one of my elbows and Paul grabs the other.

“Hit me now, shvartze,” Michael growls through the blood streaming over his lips. The first punch to my stomach steals all my breath, pain radiating from my middle. I slump for a second, giving the two boys holding me all my weight while I try to breathe. Another punch comes harder than the first, or at least more painful, and I wheeze, all the air trapped in my throat. When the third punch comes, I’m glad I can’t breathe enough to speak because I’d beg him to stop.

He draws his fist back, ready to go at me again, but Robert drops my elbow and yelps. Paul drops the other, crying out in pain.

Michael looks over my shoulder, eyes widening. “What are you—”

Before he can finish that sentence, someone pushes past me. A clarinet case slams into his chest once, twice, three times.

“L-l-leave him alone!” Kimba screams, whirling, hitting the other two boys again with her clarinet case. Paul’s face contorts with rage and he lunges for her, but on instinct, even through my breathless pain, I manage to step between him and her, bearing the brunt of his weight with a grunt. Kimba hoists the case high with both hands, poised to lower it like a hammer onto Michael’s head.

“Tru, no!” I catch the case before it lands, pulling it out of her hands and letting it drop to the ground. I loop my arms around her small, wriggling body. She strains toward Michael’s face, her fingers outstretched like claws, her face twisted in anger.

“What’s going on down there?” Our neighbor Mrs. Washington, a few yards up toward our houses, stands on her front porch, hands on hips, wearing an apron with her frown.

“Let’s get outta here,” Paul hisses, grabbing Robert’s arm and taking off.

Michael walks backward, keeping his eyes trained on me, and points one long finger. “This isn’t over, Fraction! Stay away from Hannah.”

He turns and sprints after the other two boys, rounding the corner and disappearing.

“Y’all all right?” Mrs. Washington yells.

“Yes, ma’am.” I make my mouth smile and, letting Kimba go, I wave. From her expression, I can tell Mrs. Washington doesn’t believe me, but with one last piercing look, she goes inside.

“Dammit,” I say, trying out one of the curse words I use when my mother’s nowhere around. “She’s gonna tell my parents.”

“I’m gonna tell them,” Kimba says, her expression squished into a frown.

“Oh, that’s just great. Yeah, tell them I got beaten up by some white guys from synagogue. As if my mom’s not already just looking for an excuse to pack us up and move whether Dad has a new job or not. She’d send me to live with Bubbe in New York. Is that what you want?”

Kimba blinks at me, tears gathering to a shimmer over her dark eyes. “Y-y-you…”

She closes her eyes and presses her lips together, the frustration of not getting the words out clear on her face like I’ve seen it a hundred times before.

Take your time, Tru.

“You think she’d do that?” she asks more slowly after a moment, a tear streaking down one smooth brown cheek. “Take you away?”

I can’t stand to see her cry.

“Don’t… Don’t cry. Nah. I’m just…no. Probably not. Let’s just not tell her. Everyone’s not like them. It’s not a big deal, okay?”

“It is a big deal.” She balls her small hands into fists at her side. “They punched you in the stomach.”

She steps close, lifting my T-shirt. “Are you hurt? Did they—”

“Stop.” I catch her hand, pushing it away from me, pushing her away. “I’m fine.”

We’re not babies anymore. Not little kids on the swings. Our parents sat us down last year and explained we’re too old for sleepovers, and when Kimba tries to lift my shirt to make sure I’m okay, I know we’re getting too old for a lot of things.

“They hurt you,” she whispers, letting her hand drop. “Are you sure you’re all right?”

She saw them hitting me. Saw me slumped like a wimp, short and small, while those bigger boys punched me. Shame curdles in my belly. Blood heats my cheeks. I’m white enough to blush, but too black to blend.

“I said I’m fine.” The words leave my mouth sharp as needles, pricking us both.

“But, Ezra—”

“Kimba, just stop.” I run my hands over my hair, my fingers tangling in the thick, tight curls.

My yarmulke lies on the sidewalk, marred by a dirty sneaker footprint. I bend to pick it up and twirl it like a basketball, watching it spin and spin on my finger in the silence that stretches thick as taffy between Kimba and me. A creaky, familiar song breaks the quiet, and both our heads turn toward the sound. The old ice cream truck comes into view, making its slow way up the street.

There are so many things I could say to Kimba. I want to explain how splintered I feel sometimes—how there’s something always moving inside me, searching for a place to land, to fit, to rest. I want to tell her it’s only ever still when I’m with her—that she’s my best friend in the world, and I’d rather get punched in the stomach every day than move away and not have her anymore. But that’s too many words that don’t even come close to telling her what I feel.

“Ice cream?” I ask instead, keeping my gaze trained on the rickety neon-painted truck wobbling toward us.

I cross my fingers that she won’t ask again if I’m okay because I don’t think she’d know what do with the truth. I don’t know what to do with the truth. I’m not okay sometimes. The familiar tune gets louder and closer.

Finally, she speaks. “Okay, Ezra. Ice cream.”

Chapter Four

Kimba

13 Years Old

“Psssst!”

The hiss comes as a piece of notebook-lined origami lands on my desk. I glance nervously from the little square of paper to the teacher at the front of our class. Mrs. Clay is the toughest

teacher in the whole eighth grade. She doesn’t play and I don’t test her. Ezra and I were the only black kids in the gifted classes for the longest time, though I know most don’t think of Ezra as black. They don’t know quite what to make of his blue eyes and rough curls and tanned skin. To me, he’s just my best friend.

At the beginning of this school year, another black girl showed up in class, Mona Greene. I didn’t even know how much I needed that until she came. I always have Ezra, of course, but a girl who looks like me? Has hair like me? Understands this tightrope we walk between school and home, striking the right balance between being black enough and just enough black—I love having that. Mona busses in from a neighboring district through a program the city implemented. She’s great, but she always almost gets me into trouble.

I run a finger over the paper on my desk and glance over my shoulder, catching Mona’s wide eyes. She tilts her head, silently urging me to open the note. I jerk back around and eye Mrs. Clay cautiously. When she turns to the chalkboard to write something about Charles Dickens, I slide one fingernail under a fold in the letter and ease it open as quietly as possible.

Kimba, I think you’re so pretty and smart. Will you go with me to the dance?

Yes

No

Jeremy

The dance is in two weeks, celebrating the end of middle school and sending us off in style to summer and ninth grade. Mona, Ezra and I are all going, but none of us have dates.

I glance back over my shoulder at Mona, and a mischievous grin hangs between her cheeks like a hammock.

“Oh my God,” I mouth to her, my eyes stretched.

“I know,” she mouths back, nodding enthusiastically.

A long arm reaches across the aisle and snatches the note. I gasp, grabbing to take the paper back from Ezra, but he turns his lanky body slightly away from me, grinning and batting away my hands. Mrs. Clay suddenly turns around, probably alerted by the small noises I made. Ezra and I instantly go still and inconspicuous. Her narrowed eyes scan the class row by row, but after a few seconds, she turns back to the chalkboard and resumes the lesson.

Ezra’s grin fades as he reads, melting away by centimeters. A frown squeezes between his brows. He places the paper back onto my desk, slumps in his chair and starts scribbling in the margins of his notebook. The words are in Hebrew so I have no idea what he’s writing, but he presses so hard the pencil dents the paper.

“Ez.” My voice comes out like a hissing cat, low and irritated. “Don’t read my stuff.”

“Since when?” he mumbles, not bothering to look up, his wide mouth sulky. His shoulders are parentheses, bowed, bracketing his body like they’re holding him together. “We’ve never kept secrets from each other. I thought you and Mona were just playing around. I didn’t know it was…”

He glares at the notebook and carves the Hebrew letters onto the paper, a torn black ribbon pinned to his T-shirt over his heart, a Jewish sign of mourning. It’s been a hard month for him. Bubbe died two weeks before Ezra’s Bar Mitzvah. The Sterns went up to New York right away for the funeral, even Ezra’s father who has never really gotten along with Mrs. Stern’s family. When they returned, we attended Ezra’s Bar Mitzvah at the synagogue, and the reception after. I didn’t understand everything that happened, but I knew Ezra worked hard to learn Hebrew and prepare for the ceremony. He excelled, like he does in everything. I researched the best things to give, and found out gifts in increments of eighteen are kind of like good luck, so I gave him eighteen Pixie Stix. Mrs. Stern isn’t usually strict about him keeping Kosher, but leading up to the Bar Mitzvah, he did. Pixie Stix are his favorite.

“Hey,” I whisper. “I’m sorry.”

He doesn’t answer, but the muscle in his jaw knots.

“Ezra, I—”

“Miss Allen,” Mrs. Clay cuts in, her voice like a snapping turtle. “Since you want to talk so much, you can read the passage.”

What passage?

Crap.

I hate reading out loud. On paper, I can hold my own with any of the kids in our gifted classes, but when I read aloud, the words shuffle in my mouth and strangle my tongue.

“Um, n-n-no, ma’am.” I clamp my lips together and swallow hard, closing my eyes and breathing deeply like my speech therapist suggested. “No, I don’t want t-t-to t-t-talk. I’m sorry. I—”

“It was not a request, Miss Allen.” She leans against the chalkboard, apparently uncaring that she’s probably getting chalk dust all over her beige cardigan. “Read the passage.”

“Um, o-okay.” I gulp my fear down and study the board. “Which one exactly should I—”

“The one we’ve been discussing.” Mrs. Clay huffs a long sigh. “The opening lines of the book, please.”

I glance at the book on my desk, A Tale of Two Cities, and open it to the first page. Thirty pairs of eyes wait on me. The room is so quiet, I hear them breathing, hear my own shallow, panicky breaths. My dry lips will barely part to let the words out. I lick them and try.

“I-i-t was the best of times,” I manage, my voice a croak. “It was the—”

“Louder so we can hear you. And please stand. You know the drill by now.”

A drill I’ve avoided as much as possible the whole school year. I’m all sass and confidence in every other class and every other area of my life, but this one? Reading out loud? In front of everyone? Risking the disdain of the smartest kids in our school when my tongue lets me down? I’m terrified.

Picking up the book, I stand. “I-i-it was the best of times—”

Snickers break out behind me. I pause at my classmates’ amusement, drawing a deep breath and starting again.

“I-it was the best of times—”

Whispers. Chuckles. Gasps from behind stop me again. I look around, glance over my shoulder and find Mona’s eyes. They are wide, shocked. Her mouth hangs open and she covers it with one hand.

Before I can process the amused and surprised expressions all around me, Ezra stands and ties his windbreaker around my waist.

“What are you doing?” I ask him. “What’s—”

He grabs my hand and fast-walks me down the row of desks and out the door without speaking. I look back, expecting Mrs. Clay’s fury, but her face has softened. When her eyes meet mine, they’re compassionate.

“All right, class,” she says, her curt tone back in place. “That’s enough. Let’s get back to it. Darlene, would you read the passage?”

Ezra pulls me out the door and starts down the hall. I tug at my hand, trying to free it.

“What are you doing? Where are we going?”

He doesn’t answer, but just keeps walking. I jerk my hand away and stop in the middle of the hall.

“Ezra, I know you’ve used your, like, twelve words for the day,” I say, hands planted on my hips, “but you better tell me what’s going on right now.”

He stops, too, running a hand through his hair.

“Kimba, I…you…” He groans and closes his eyes.

“Just spit it out. What in the world? You tie this jacket around my…” I trail off, my brain finally catching up to wonder why he did that.

“There’s a stain on the back of your pants,” he mumbles, his eyes glued to the floor as he drags the words past his lips.

“A stain?”

Fire ignites beneath the surface of my cheeks. My fingertips go cold. My stomach lurches. I got my period for the first time two months ago. Kayla told me horror stories about this happening at school, and I’ve tried to be so careful. But today, I wore white shoes and white pants. I sit close to the front of Mrs. Clay’s class, so all those students sitting behind me saw…

“Oh, God.”

I take off running down the hall toward the bathroom, tightening the sleeves of Ezra’s windbreaker around my waist. Ezra’s footsteps behind me only urge me faster. I need to get away even from him.

“Tru!” he calls, but I keep moving. He catches up to me and takes my arm. “You okay?”

“Besides being dead from embarrassment?” I mumble, avoiding his eyes. “Yeah. Peachy.”

“Those kids don’t matter,” he says, flicking his head in the direction of the class we just fled. “And you know you don’t have to be embarrassed with me.”

I look up to meet his eyes, and they’re dark blue, almost violet. I love that color so much, but hate that it only comes when he’s upset. “I’m okay, Ezra. Thank you for the jacket.”

I start to untie it, but he places a hand over mine.

“Keep it until you don’t need it,” he says, his voice scratchy with discomfort. “I’ll get it later. I know where you live.”

We chuckle.

“Yup, right across the street.” I smile, but squeeze his hand over mine. “Thanks, Ez. You always take care of me.”

“We take care of each other,” he says, his voice subdued when he looks up from our hands, his eyes intense. “Hazak, Hazak, Venithazek.”

It sounds like Hebrew, but I have no idea what it means. “What’d you say?”

“Be strong, very strong.” His fingers tighten on mine and he doesn’t drop his gaze or slide a hand in his pocket, or any of the other Ezra things he does when he’s unsure. “And we will strengthen each other.”

The words are seeds sinking deep into my soul, into my heart. They take root and bloom. We’ve taken care of each other our whole lives. I don’t know what to do with these feelings. What I feel for Ezra is as old as we are, and yet brand new. It’s familiar, but blushing and breathless.

“Mr. Stern, Miss Allen,” the vice principal calls from a few feet down the hall. “Shouldn’t you be in class?”

“I have a female issue.”

I’ve only had my period twice, but I’ve already discovered you only have to refer to it for men to start stumbling and looking uncomfortable.

“Well, yes.” He tugs at his tie and clears his throat. “You, um, do what needs to be done.”

He points to Ezra. “You don’t have a, um, problem like that, Mr. Stern. Get to class.”

“Yes, sir.” Ezra looks at me, a small smile on his lips. “I’ll see you later, okay?”