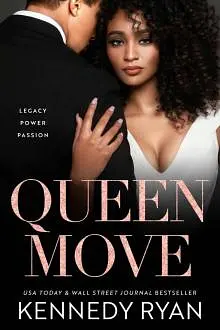

by Kennedy Ryan

“Yes, a man can, but this man usually doesn’t.” I chuckle to let him off the hook because he’s that guy who makes everybody want to let him off. “I know you need something, but it’s good to hear from you. What’s up?”

“I heard you’re coming home and might stay for a while.”

“Maybe a couple of weeks.” I perch on the edge of my desk. “We’ll see.”

“I’d love to talk to you about something while you’re home.”

Here we go.

“Oh?” I ask, keeping my voice only pleasantly curious instead of I knew it. “What about?”

“I’m thinking of running.”

“From who?” I ask, laughing.

“Ha ha. Very funny. Running for office.”

My smile disintegrates. “Which office?”

“Congress. I’ve been putting some feelers out, and there’s real interest in me getting into politics.”

“Of course there’s interest. Your last name is on a dozen streets and schools and parks in that city. Name recognition alone means somebody wants to slap you onto a ballot. Doesn’t mean you should.”

“Wow. Tell me how you really feel, sis.”

“Oh, I always will. You know that. Why do you want to run for office? You’re making plenty of money practicing law.”

“It’s not about the money,” he says, his tone stiffening like one of his heavily starched shirt collars.

“What is it about then? Tell me.”

“It’s about…the people.”

“What about them?”

“I…well, I want to help them, of course.”

“Help them how? Tell me their issues. Tell me their problems. What’s the average income for people in that district? How are the working poor faring? Graduation rate? Voter suppression is rampant. What do you plan to do about it?”

“Whoa, whoa, whoa. Why are you attacking me?”

“Attacking you?” I suck my teeth. “Boy, please, you ain’t ready. If you think this is an attack, try being in a debate, a hostile interview. I’m giving you the chance to show me you care about the people you would be representing. That you care enough to know how you can help them, not how this opportunity could help you.”

“You put every client though this wringer before you take them on?”

Oh, he has no idea.

“You still stepping out on Delaney?” I ask, going for that weak spot he thinks I don’t know about.

The silence between us is sticky and pulls like syrup.

“What?” he finally asks. “I don’t know—”

“I said are you still cheating on your wife?”

I hear him swallow, but no answer.

“Get your house in order,” I tell him, “before you think about running for mine.”

“Your house?”

“Oh, yes, sir. I grew up in that district, Stoke, and I may not live there now, but I’ll be damned if I’ll send an ill-prepared, incompetent narcissist who can’t keep his dick in his pants to the House of Representatives on their behalf. We have enough of those already. And I don’t care if you’re my brother. If you’re not in it for the people, you could be my Siamese twin and I wouldn’t stand with you.”

“Damn, sis. It’s like that?”

“It’s like that. What do you think I do? You think I elected a president accepting bullshit answers to tough questions? If I work with you, and that’s a big if because I’ll tell you right now, I’m not impressed, I will not be played…bruh.”

“You telling me the guys you help win elections don’t cheat on their wives?”

“Of course, half of them do. Probably more, but they aren’t carrying my last name into office.” I pause for a second before going on. “Plus, it’s trifling and your father raised you better than that.”

He doesn’t reply, but I hope he’s thinking about it.

“Be better prepared when I come home next week,” I finally say softly, “and we’ll see.”

“Thanks, Kimba.”

“I said we’ll see.” I will the rod in my back to relax. “I love you.”

“Love you, too.”

“Kiss Delaney and the kids for me.”

He hesitates. “I will.”

I was hard on him, but he does have potential. And he comes from a long line of activists. I’ll help him if he’s in it for the right reasons. I’d help him because I know it would make Daddy proud—that there’s nothing he’d like better than to see his only son having an impact in the city our family has given so much to.

“I got you, Daddy,” I whisper, walking over to look at D.C. sprawled beneath my office window. “I got you.”

Chapter Thirteen

Ezra

“Our beans are better,” Noah whispers to me behind his small hand.

I spear a green bean tucked beneath the stuffed chicken breast and pop it into my mouth. “You’re right. Our garden is the bomb. We grow great veggies.”

We execute an exploding fist bump.

“You know my favorite kind of vegetables?” Mona asks beside me, spooning up a portion of mashed potatoes. “Free.”

The three of us laugh, as usual with Mona. The awards committee provided tickets for two guests. Noah was the obvious choice, and Mona since Aiko is out of town.

“Thanks for inviting me,” Mona says.

“Thanks for coming.”

“This is really an honor, Ezra. The whole staff is proud of you. Wait ’til your book comes out. You won’t be able to shut us up.”

I can’t help but feel proud, too. I’m writing a book about the YLA journey, and someone actually wants to publish it.

“I heard Kimba’s coming,” Mona says.

My head snaps around. “What?”

“Yeah, I ran into Kayla in the bathroom and she mentioned it. I haven’t seen them in years. We all kinda went our separate ways, huh?”

After Mom and I left, we spent the summer in New York with family. I went to camp and assumed we’d head back to Atlanta. Mom didn’t get to stay in New York for long. Before school started, my father accepted a job offer in Italy. Moving there was the best and worst thing for me. The best because even though I didn’t speak the language and it was a foreign country, I looked like many of the people. I blended in. No one asked my mother if I was adopted or stared at us when I was with my parents. I could breathe in Italy in a way I hadn’t felt free enough to do before, and it came just as I was becoming a young man—just when I needed it.

The worst was losing contact with Kimba. Her family moved, changed their phone number. This was before Facebook or Instagram. I had no idea how to get in touch with her, and with us in Europe, she had no way to get in touch with me. Mona told me later she didn’t bus in for high school, but stayed in her district, so she didn’t see Kimba anymore either.

“I wonder if she’ll actually show.” I sip my water and peruse the room slowly, searching each table and aisle for her. I’ve seen her on television a few times, but her partner, Lennix Hunter, now the First Lady, usually spoke on behalf of their clients. “It’s almost time to give out the awards.”

“Kayla said something about her flight out of D.C. being delayed.” Mona shrugs. “I think she’s taking a little time off and hanging here in Atlanta for a few weeks. Hopefully we can get together while she’s in town.”

I take another sip of water, disciplining my expression into impassivity. Inside, though, anticipation churns through my body. Kimba and I will be in the same state, maybe around each other, for the first time since we were thirteen years old.

“Whose flight is delayed?” Noah asks, taking a sip of the sweet tea.

“No more.” I point to his glass. “Water for the rest of the night.”

He crosses his eyes, which is his new thing he learned to do last week. “Okay, but whose flight?”

“Our friend Kimba,” Mona says. “We haven’t seen her in a long time.”

“The one we met at her daddy’s funeral?” Noah asks me.

> “Yeah, that’s the one,” I reply, surprised he remembers. Though Noah has the memory of an elephant, so I shouldn’t be.

“I hate I was out of town for the funeral,” Mona says. “I would have loved to pay my respects and to see Kimba again. Funny how people you’re so close to when you’re kids, you don’t even see for years and years. Decades even.”

It doesn’t feel funny to me. It feels tragic that the person I thought I’d know all my life is now a veritable stranger. Someone whose sentences I used to be able to finish. The few secrets I had at that age, Kimba kept. Now I don’t know her at all.

“It’s time.” Mona nods toward the stage where Kayla stands behind the podium.

It’s hard to reconcile this mature, almost staid woman and her closely cropped hair with the Kayla who used to show off her gold package Nissan Maxima all around our neighborhood.

“Good evening, everyone,” Kayla says, spreading a warm smile across the crowd. “I’m Kayla Allen-Greggs, executive director of the Allen Foundation. I hope you’ve enjoyed the night so far.”

“Not the beans,” Noah mutters, pushing what’s left of his food around his plate. “How much longer?”

“Not much longer. You’ve done great.” I push his floppy hair off his forehead and chuckle. “We can grab ice cream at The Ice Box when we leave.”

He fist pumps and I turn my attention back to Kayla, stuffing my disappointment since it looks like Kimba won’t make it in time.

“This project acknowledging service excellence in our community was one of the last things my father worked on,” Kayla says. “He wanted my sister, Kimba, to make these presentations. Come on out, sis.”

Kimba walks swiftly from backstage to the podium, looking slightly harried.

And stunning.

Just like I remember from the funeral, but better, which I didn’t think was possible. Rarely have I felt so completely focused on the smallest details of another person. The gold dress caresses her body, clinging to her curves, teasing me with tantalizing glimpses of glowing brown skin. Her textured curls are caught up high, leaving the graceful lines of her neck and shoulders bare.

“Good evening everyone,” Kimba says, her husky voice shaping the words to roll over my nerve endings. “My flight was delayed and I wasn’t sure I’d make it in time. I’m so glad I did.”

She draws a deep breath and grips the edge of the podium before going on.

“My father always used to say whatever you do, be excellent,” Kimba says. “Whatever you do, consider others. Big moves make big waves. Do big things. Make big waves. Tonight’s amazing leaders were selected because of the waves they’re making in our community. Sometimes we don’t realize that the move we’re making will be the one that changes everything, not just for us, but for someone else. Thank you for impacting your community as you follow your dreams.”

“She’s beautiful,” Mona says beside me. “Can you believe that’s our girl from middle school?”

“Hard to believe,” I agree neutrally.

“For our first award,” Kimba says, reading from the pages Kayla slid in front of her. “This doctor opened a clinic offering free mammograms to at-risk women with inadequate insurance coverage. Dr. Richard Clemmons.”

Dr. Clemmons takes the stage with Kimba, she hands him his award, and they pose for a photo before she moves on to the next recipient on her list. I have no idea where I fall in the order. Does she know I’m here? Did her mother or Kayla know? Connect the dots between the Dr. Ezra Stern who opened the school and the kid who darkened their door basically every day from the time he could walk until his parents dragged him away?

“Next,” Kimba says when she’s about halfway through the recipients. “He founded and runs a private middle school serving low-income areas and at-risk students, ninety percent of whom are on scholarship. Students at the Young Leaders Academy of Atlanta have experienced, on average, an eighty percent improvement on test scores. This award in the area of educational excellence goes to…”

She falters, a frown gathering between her dark brows. She lifts her head abruptly, scanning the room and then doing a slower pass until she finds me in the corner.

“Ezra.”

The room goes quiet for a second, the audience waiting for her to continue. She shakes her head. “Um, sorry. Dr. Ezra Stern.”

Noah stands in his chair and claps and whistles and hoots. Mona hugs me, squeezing my shoulder. As soon as she lets go, she pulls the phone from her pocket and aims it at me.

“Video for everybody at school!” Mona says, laughing at what I’m sure is my exasperated expression when she thrusts the camera in my face.

I head toward the stage, smiling at the people standing and clapping as I pass. I have a vague impression of their faces, but I don’t hear their applause over the clanging cymbal in my chest. Onstage, Kimba’s smile flickers like candlelight. There’s something uncertain on her face, in her eyes. I recognize it. I feel it, too. Ever since I read the email about this night, this moment loomed like a promise or a threat. The moment when I would see Kimba again.

When I reach the stage, she hands me the award, and we both turn for a photo.

“We have to stop meeting like this,” she jokes, slanting a smile up at me.

“How would you like for us to meet?” I ask, trying to force a smile, but I can’t. I mean it. It’s not an idle question, and I can’t make the moment as light as it should be. Seeing her only twice in more than twenty years feels wrong. It’s never felt right to be apart from the person who once knew me better than anyone else—who knew me even as I was learning myself. When I saw her before at her father’s funeral, what crackled between us felt like danger, the possibility of all that could go wrong. But now, I’m free. This time when our eyes meet, I can’t help but wonder, if given the chance, what between us could go right?

Chapter Fourteen

Kimba

“You’re a doctor?”

A dozen thoughts collide in my mind once we’re off the stage and standing with all the recipients, awaiting a group photo, but that’s the one I blurt out. I presented several other awards after Ezra’s, but I couldn’t tell you any of the recipients’ names. I don’t remember their faces. On autopilot, I presented the awards and smiled and posed, but all the while, I knew exactly where Ezra stood with the others behind me onstage. I could feel his stare—the heat and intensity of it tingling across the bare skin of my neck. As soon as all the awards were announced, I wasn’t surprised when Ezra immediately appeared at my side.

“Of sorts,” he replies to my question, shrugging. “Ed.D.”

“Daddy!” The shout comes from the boy who is bigger and more like Ezra than the first time I saw him at the funeral. Noah throws his arms around his father, burying his face in his side. “You won.”

“It wasn’t a competition, son,” Ezra says dryly, brushing a hand over his hair.

“I tried to explain,” says an attractive woman around our age with dreadlocks pulled into a regal arrangement just behind Noah. “But he wasn’t having it. You’re a winner in his eyes.”

I remember Ezra’s wife vividly, a petite woman of Asian ancestry. This woman doesn’t look anything like that, but she does look vaguely familiar.

“All that squinting,” she says, turning laughing dark eyes on me. “And you still haven’t figured out who I am?”

“We have met, right?” I ask, hating to admit I don’t recognize someone, but too curious to pretend.

“He was Jack,” she says, nodding to Ezra. “You were Chrissy, and I was—”

“Janet!” I shout, pulling her into a fierce hug. “Oh my God, Mona.”

Tears prick my eyes, and I’m probably holding her too tight, but I’m overcome with how good it feels to see her again. When her parents decided she wouldn’t bus into our district for high school, we kept in touch at first, but didn’t maintain the friendship, caught up in new schools, new friends, and all the changes that came with growing up and inevit

ably growing apart. Eventually, with Ezra and Mona both gone, I found a new circle of friends, and so did she. I heard snatches of news about her until I left for college, and then nothing—until now.

“I’ll let you off the hook because it’s been so long since we saw each other,” Mona says, pulling away to look me up and down. “Well, that and you gave us one of the best presidents this country has seen in recent memory. Congratulations, Kimba. When I saw you on CNN, I couldn’t believe you were the same girl who hated reading out loud in class.”

My cheeks go hot, which hasn’t happened to me in years. Sometimes I’m shocked to hear my own voice, my words strong and clear and flowing. Who would believe the girl rattling off stats and details in front of a camera, for millions of viewers, used to hate reading in front of her classmates?

I look up to meet Ezra’s stare, and I know he’s remembering that day in Mrs. Clay’s class. I’d forgotten this kind of telepathy we share, seemingly conducting thoughts between our minds with nothing more than a glance. There’s a disconcerting intimacy to it that feels wrong when his mind isn’t mine. Neither is his face, which settled into a roughly hewn beauty that I can barely tear my eyes from, or the big body standing like a tree offering shelter. I’m not his to shield. He’s not mine to shelter. We’re not each other’s anymore.

I guess we never were.

“Wait,” I say, looking between my old friends. “So you guys stayed in touch?”

“Not until we ran into each other a couple of years ago at a teacher’s job fair,” Mona says.

“I was staffing the school,” Ezra says. “And there was Mona. She practically runs the place now.”

“Now, we know that’s a lie.” Mona tsks. “This one’s a control freak. It’s bad enough I have to put up with him at school. Then we bought houses next door to each other. Aiko’s a good neighbor, even if he isn’t.”