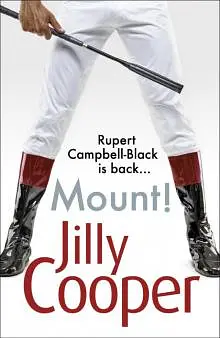

by Jilly Cooper

Even worse, Isa had joined forces with Cosmo Rannaldini, the fiendish little son of Rupert’s arch enemy, the late, great conductor Roberto Rannaldini. Married to Rupert’s first wife Helen, Roberto had not only tried to rape Rupert’s daughter Tabitha, but had managed to batter to death Taggie’s little mongrel Gertrude when she tried to protect Tabitha. In the Campbell-Black canon, it was arguable which was the greater crime.

Cosmo and Isa were proving maddeningly successful with the progeny of Roberto’s Revenge, particularly with a colt called Feud for Thought, which had just beaten Rupert’s colt Dardanius in the Derby. Cosmo had inherited a great deal of money from his father, but he and Isa were spending such a fortune on yearlings and two-year-olds that someone must be bankrolling them. Rupert would kill to stop them beating him to Leading Sire. Love Rat must topple Verdi’s Requiem.

In the still-baking evening, out in the fields he could see foals lying flat and motionless except for their frantically waving tails. Rupert’s four dogs: Jack Russells, Cuthbert and Gilchrist, a brindle greyhound called Forester and a black Labrador called Banquo, panted in their baskets.

Up on a monitor, evening racing had started at the Curragh, Ireland’s greatest racecourse. Rupert hoped one of Love Rat’s progeny, Promiscuous, would win a later race there.

Promiscuous had been trained by Rupert’s old stable jockey, the also lascivious Bluey Charteris, who’d married an Irish trainer’s daughter, and managed to stay faithful enough to take over his father-in-law’s yard. Bluey and Isa Lovell doing so well made Rupert feel old. Overwhelmed with sadness and restlessness, he rang Valent Edwards, who had just married Etta Bancroft, the owner of Grand National-winning Mrs Wilkinson, and who was now back from their honeymoon.

‘We ought to discuss Mrs Wilkinson,’ he said. ‘Come over and have a drink.’

The moment he rang off, the telephone rang again: ‘No, you can’t have a discount on three mares,’ said Rupert tersely, and poured himself another glass of whisky.

There was a knock on the door and a very pretty blonde, with an utterly deceptive air of innocence, walked in. Dora Belvedon was the eighteen-year-old daughter of Rupert’s late friend, Raymond Belvedon, and his much younger second wife, Anthea. A gold-digger and an absolute bitch, Anthea had never given Dora enough pocket money. As a result, Dora had supported herself, her dog Cadbury and her pony Loofah by flogging stories to the tabloids.

For the past two years, as well as acting sporadically as Rupert’s press officer, she had been ghosting his contentious, highly successful column in the Racing Post. She also wrote a column supposedly by Mrs Wilkinson’s stable companion, a goat called Chisolm, in the Daily Mirror.

Missing her sweet father desperately, an itinerant Dora found comfort spending time at Penscombe, where she could always grab a bed if needs be. In addition, she often stayed in Willowwood, in the cottage of Miss Painswick, the former secretary of her old boarding school.

Fearing that Mrs Wilkinson might be homesick just before the Grand National, when she had been moved to Penscombe to be trained by Rupert, Dora, in an incredibly daring move, had smuggled the little mare into the mighty Love Rat’s stallion paddock, and a joyful coupling had taken place.

Mrs Wilkinson’s dam had been a successful flat horse called Usurper, and her sire was Rupert’s most successful stallion: the Derby and St Leger-winning Peppy Koala. As Love Rat had been a champion sprinter, who would add his lightning speed to Mrs Wilkinson’s stamina, any foal consequently should be a cracker. But as Dora had executed this move without Rupert’s permission, she was extremely anxious to avoid the subject of stud fees. Now, brandishing an Italian phrasebook, she said, ‘Poor Emilia was awfully low, but I’ve been talking to her in Italian and she’s really perked up’ – Emilia being a very good filly Rupert had bought cheap because of the collapsing Italian economy.

‘I’ve also been playing her La Traviata,’ babbled Dora, ‘and she loved it, particularly the bit that goes, “Da dum dum da de dum, da dum, dum da, de, dum”.’

‘Where the hell have you been?’ demanded Rupert, who adored Dora but felt she needed reining in.

Dora replied that she’d been in Sardinia with her actor boyfriend Paris, and housesitting Mrs Wilkinson while Etta her owner and her husband Valent were on their honeymoon.

‘It’s Mrs Wilkinson we’ve got to talk about,’ Rupert said.

‘I must get your Racing Post copy in by tomorrow afternoon,’ Dora said hastily. ‘I thought you might like to write about Roberto’s Revenge’s climb up the Leading Sire’s chart. Isa Lovell’s doing really well.’

‘I’m not doing any favours for that moody, vindictive little shit, or that oily little toad Cosmo.’

‘I quite like Cosmo,’ confessed Dora. ‘He’s funny and we both have mothers who are embarrassingly bats about you.’

‘Shut up, Dora,’ snapped Rupert. ‘We need to talk about Mrs Wilkinson.’

‘Did you see Amanda Platell’s piece in the Mail, about the doctors’ surgeries teeming with women suffering from loss of libido, and suggesting the perfect cure was Rupert Campbell-Black?’

‘Don’t be even more fatuous,’ said Rupert irritably. But he smirked slightly. ‘Now about this stolen service.’

On cue, Dora’s chocolate Labrador, Cadbury, wandered in from Taggie’s kitchen, and all Rupert’s dogs woke up and fell on him, barking joyously. ‘Go back to your boxes. Stop that bloody awful din!’ roared Rupert.

‘Din, because they want their dinner, ha, ha. Can Cadbury have some too?’

‘Shut up, Cuthbert.’ Rupert pulled a Jack Russell on to his knee, shutting its yapping jaws with his hand and asked: ‘Can you remember exactly what day Love Rat covered Mrs Wilkinson?’

‘About a fortnight before the National.’

Rupert looked up at the calendar. ‘Foal in February then.’

‘Mrs Wilkinson’s had a lovely day,’ sighed Dora, edging off the subject again, ‘opening a supermarket in Cotchester. Huge cheering crowds turned out to pat her and Chisolm. They do adore the attention.’

‘With a valuable foal inside, she ought to be taking it easy.’

‘Mares can run up to a hundred and twenty days,’ chided Dora. ‘Mrs Wilkinson’s a working mother, has to earn her keep.’ Then, deflecting Rupert’s shaft of disapproval: ‘And did you know that people are Skyping Chisolm from all over the world? She’s got a website called Skypegoat. Isn’t that a cool joke?’

‘Quite,’ said Rupert, who was then fortunately distracted by a monitor on which jockeys and horses were going down to the start of the Curragh. There was Promiscuous, son of Love Rat, looking really well.

Dora looked out of one window at the squirrels fighting in the angelic green of Rupert’s beechwoods, which formed a great crescent round the rear of the house.

Turning back to Dora, Rupert said: ‘Do you realize Love Rat’s stud fee is £100,000?’

‘Goodness,’ she said, then gave a sigh of relief as Valent walked in. ‘Hi, Valent, hope you had a lovely honeymoon. Mrs Wilkinson missed you both. Must go and counsel Emilia some more. Dum, da, da, dum de dum,’ sang Dora as beaming, followed by five dogs, she sidled out of the room.

2

Rupert respected Valent Edwards. He couldn’t push him around and, despite being strong, tough and hugely successful, Valent didn’t take himself at all seriously; nor, although humble about his working-class origins, was he remotely chippy. An ex-Premier League footballer, whose legendary Cup Final-winning save was still remembered, Valent had been a great athlete who, like Rupert, on giving up had channelled his ambition and killer instinct into finding gaps in world markets. The fact that both men had made a huge amount of money didn’t deter them from being hell bent on beating their rivals and making a great deal more.

In his late sixties, tall, handsome, hefty of shoulder and square of jaw, with black eyebrows and grey hair rising thickly without the aid of any product, Valent had been described by Louise Malone, one of Rupert’s m

ost comely stable lasses as: ‘A cross between my dad and my granddad, but you still want to shag him.’

Having married Mrs Wilkinson’s owner, Etta Bancroft, Valent had returned from a four-week honeymoon looking tanned and happy.

‘How was it?’ asked Rupert, handing him a can of beer.

‘Grite, went by in a flash.’

‘You were bloody lucky, it’s been raining since you left.’

Glancing round the room, Valent caught sight of the Stubbs. ‘Christ, that’s you.’

‘No, a distant ancestor, Rupert Black.’

Valent moved closer. ‘But he’s exactly like you,’ he said incredulously. ‘Where d’you get it from?’

‘It somehow got handed down to some queer uncle, who left it to me. Should have left it to my brother, Adrian, who’s an art dealer, but I’m better-looking. Adrian’s livid. Stubbs was a leftie and usually painted racehorses held by their stable lads, but Rupert Black was so up himself, he insisted on riding the horse – a Leading Sire, no less, called Third Leopard. Perhaps I ought to start riding Love Rat.’

Valent shook his head. ‘He is so like you.’

‘Classic case of pre-potency,’ explained Rupert. ‘Some stallions (like some men) have genes so strong, they imprint their looks and temperaments on succeeding generations. So for generations, the offspring are far more like them than their immediate fathers or grandfathers.’

Rupert, who hadn’t had any lunch, opened a tin of Pringles and handed them to Valent who, having put on ten pounds during his honeymoon, waved them away.

‘For example, two hundred-odd years later,’ went on Rupert, ‘I look far more like Rupert Black than my own father, while Tabitha and Perdita, my daughters, and Eddie, my grandson, are all the image of Rupert Black. They have also inherited his brilliance as a rider, his arrogance, his tricky temperament and the same killer instinct.’

‘And stooning looks.’ Although as the sun fell on the indigo shadows beneath Rupert’s eyes, Valent thought he looked desperately tired. ‘What do you know about him?’

‘Not a lot. His father was a trainer, and Rupert Black won a match race which apparently enabled him to buy Third Leopard. As I said, the horse became Leading Sire, making Rupert a fortune in stud fees. And talking of Leading Sires, one of Love Rat’s colts is in this race …’ Turning up the sound, Rupert became totally superglued to the television.

‘Come on, little boy, come on, little boy … come on, come on, come on!’ he yelled, giving a shout of joy as Promiscuous left the field for dead and romped home by three lengths.

Through the open window, cheers could be heard from stable lads watching the race on television screens all over the yard and stud. Next moment, a bell rang to announce a winner, which always raised morale.

Looking out, Valent could see Rupert’s beautiful wife Taggie crossing the yard on her way to the stud to reward the winner’s sire Love Rat with a carrot.

‘Bloody good result. That’s two Group Ones and a Group Two won by Love Rat’s progeny this week,’ said Rupert happily. He picked up his mobile to share the news with Billy, who had also loved Promiscuous, then realized the futility. God, would it never stop hurting?

Valent, meanwhile, was thinking about Etta, his new wife, and dreading getting caught up in work again. They could have stayed away more than a month, but Etta couldn’t bear to be parted any longer from Priceless, her greyhound, Gwenny her cat, Mrs Wilkinson and her stable companion, Chisolm the goat, and the garden in the growing season.

There were, in fact, few places abroad where some stray dog or cat wouldn’t upset Etta. He longed to take her to China where he had been doing a huge amount of business, but felt a country where dogs were rammed into cages in the marketplace on the way to the dinner-table would finish her off completely. So they had returned home and it was blissful to be back at his house, Badger’s Court, in the nearby village of Willowwood. He had left Etta pruning roses and wailing at the bindweed toppling the delphiniums and the brown slugs, bigger than Dora’s chocolate Labrador, eating everything.

Suddenly he noticed a large, dark-brown horse with only one ear wandering out of his box in the direction of the feed room.

‘Loose horse,’ he said in alarm. Rupert glanced out.

‘No, that’s Safety Car – got the run of the yard.’

‘Why’s he only got one ear?’

‘Titus Andronicus, the yard sociopath, bit the other off and most of his tail.’

As Taggie came out of Love Rat’s box, she apologized to Safety Car for giving away her last carrot, then glanced tentatively up at the window, waving shyly at Valent before disappearing back into the house, followed purposefully by Safety Car.

‘We’d better talk about Mrs Wilkinson’s foal,’ said Valent.

Mrs Wilkinson had originally been rescued by Valent’s new wife Etta. Nursed back to health, she had turned out to have an immaculate pedigree. To afford to put her into training, Etta had formed a syndicate of fellow villagers living in Willowwood.

Back in March, after Mrs Wilkinson fell in the Cheltenham Gold Cup, Valent had bought her to stop her being acquired by a very unpleasant rival owner. When Rupert suggested she had a crack at the National in three weeks’ time, Mrs Wilkinson, when transferred to Rupert’s yard, had detested the draconian regime. It was here, to cheer her up, that Dora had sneaked her into stallion Love Rat’s paddock. Thus encouraged, Mrs Wilkinson had gone on to win the National.

Rupert, in fact, had been winding Dora up about stud fees, because Mrs Wilkinson actually belonged to Valent, who would own any foal born and therefore be responsible for stud fees. Having handed Valent another beer, Rupert foxily announced that foal shares were standard these days, and that if he and Valent shared ownership of the foal, he would train it for nothing.

Valent liked and admired Rupert, whom he was also aware he couldn’t push around. He was also slightly edgy about him, not least because Rupert had been Etta’s long-term pin-up. But although it would be most women’s idea of heaven to share ownership of a potential superhorse with Rupert Campbell-Black, Valent knew that Etta felt Rupert was too rough on horses, regarding them as marketable stock rather than furry animals to be adored.

‘I’d also be waiving Love Rat’s £120,000 stud fee,’ Rupert added.

‘You told Dora £100,000.’

‘Varies,’ said Rupert airily. ‘What’s the state of play with that ghastly syndicate?’

‘They still own ten per cent of Mrs Wilkinson.’

‘Get rid of them, pay them off.’

‘Here’s the contract.’ Valent had some difficulty extracting it from the pocket of his newly tight trousers before handing it to Rupert, who scanned it.

‘Thank Christ, there’s nothing about breeding rights, so the foal’s ours.’

‘I’ll talk to Etta,’ said Valent firmly. ‘I gave Wilkie back to her as a wedding present.’

He then moved on to discuss China, where racing was almost entirely forbidden because the Communist regime, like the Bishop of Rutminster back in the eighteenth century, thought it a corrupting influence, particularly the betting side.

Hong Kong, however, which offered vast prize money, made more in tax on the day of the Hong Kong Cup than the country did in an entire year – money which also paid for all the hospitals. An impressed China was therefore seriously considering establishing an indigenous racing and breeding industry. There were already plans afoot to build two international racecourses, five training tracks and to provide stabling and facilities for 4,000 horses.

‘The potential of this market is so vast,’ said Valent, starting on the Pringles, ‘with bloodstock agents all over the world salivating at the prospect of selling horses to China.’

‘The Irish and the Arabs are already doing deals and sending stallions,’ volunteered Rupert. ‘Imagine The Morning Line with 400 million viewers.’

‘I’ve got the contacts, but not the expert knowledge.’

‘Then you’d better

acquire some,’ said Rupert.

3

Rupert whisked Valent through the racing yard, into Penscombe Stud and past a row of boxes, known as Billionaire’s Row because it housed Rupert’s finest stallions, and included the house of Pat Inglis the Stallion Master, so he could keep an eye on them all. Each stallion had a brass plate with his name on attached to the cheek-piece of his head collar.

‘Much better than those name-badges at parties, when you have to surreptitiously glance down at a person’s bosom to check who they are,’ observed Valent. ‘Here you can look your stallion in the eye.’

Rupert, a gambler like his ancestor Rupert Black, had a few years ago had a successful bet that he could get a GCSE in English Literature as a very mature student. Acquiring a fondness for the subject, he had named his more recent horses after characters in Shakespeare.

Valent proceeded to admire Thane of Fife, dark brown and workmanlike, who had no trouble covering three mares a day, with a strike rate of getting 90 per cent of them in foal.

‘Didn’t win that many big races,’ explained Rupert, ‘so his stud fee is a third of Love Rat’s.’

Next Bassanio, who was very shy and could only perform if Dorothy the practice mare stood in the corner of the covering shed watching him.

Then prowling Titus Andronicus, a black brute who descended on mares like the Heavy Brigade, and who so terrified the stable lads, he was sometimes dispatched down a tunnel of cages to the covering shed.

‘One day he’ll have you against the wall, another he’ll be sweet as pie. I hope his foals don’t inherit his temperament,’ said Rupert.

They had reached the box of Hamlet’s Ghost, who only fancied greys.

‘The only way to get him to mount a mare of any other colour,’ Rupert told Valent, ‘is to put a white sheet over her.’

Enobarbus’s box was empty. He was spending a season in France and not enjoying it, because he couldn’t get a grip on the quarters of those slim French mares.

Valent shook his head. ‘They’re all different.’