20. CARLISLE

WE WALKED BACK ALONG THE HALL TO CARLISLE’S OFFICE. I PAUSED AT the door, waiting for his invitation.

“Come in,” Carlisle said.

I led her inside and watched her animatedly examine this new room. It was darker than the rest of the house; the deep mahogany wood reminded him of his earliest home. Her eyes ran across the rows and rows of books. I knew her well enough to see that the sight of so many books in one room was something of a dream to her.

Carlisle marked the page in the one he was reading and then stood to welcome us.

“What can I do for you?” he asked.

Of course, he’d heard all our conversation in the hall, and he knew we were here for the next installment. He wasn’t bothered by my sharing his story; he didn’t seem surprised that I would tell her everything.

“I wanted to show Bella some of our history. Well, your history, actually.”

“We didn’t mean to disturb you,” Bella said quietly.

“Not at all,” Carlisle assured her. “Where are you going to start?”

“The Waggoner,” I said.

I put one hand on her shoulder and turned her gently to face the wall behind us. I heard her heartbeat react to my touch, and then Carlisle’s almost silent laugh at her reaction.

Interesting, he thought.

I watched Bella’s eyes widen as she took in the gallery wall of Carlisle’s office. I could imagine the way it might disorient a person seeing it for the first time. There were seventy-three works, in all sizes, mediums, and colors, crammed together like a wall-sized puzzle with only rectangular pieces. Her gaze couldn’t find anywhere to settle.

I took her hand and led her to the beginning. Carlisle followed. As on the page of a book, the story began at the far left. It was not a showy piece, monochromatic and maplike. In fact, it was part of a map, hand-painted by an amateur cartographer, one of the very few originals that had survived the centuries.

Her brows furrowed.

“London in the sixteen fifties,” I explained.

“The London of my youth,” Carlisle added from a few feet behind us. Bella flinched, surprised by his closeness. Of course she wouldn’t have heard his movements. I squeezed her hand, trying to reassure her. This house was a strange place for her to be, but nothing here would hurt her.

“Will you tell the story?” I asked him, and Bella turned to see what he would say.

I’m sorry, I wish I could.

He smiled at Bella and spoke aloud to her. “I would, but I’m actually running a bit late. The hospital called this morning—Dr. Snow is taking a sick day. Besides”—he looked to me—“you know the stories as well as I do.”

Carlisle smiled warmly at Bella as he exited. Once he had gone, she turned back to examine the small painting again.

“What happened then?” she asked after a moment. “When he realized what had happened to him?”

Automatically, I looked to a larger painting, one column over and one row down. It wasn’t a cheerful image: a gloomy, deserted landscape, a sky thick with oppressive clouds, colors that seemed to suggest the sun would never return. Carlisle had seen this piece through the window of a minor castle in Scotland. It so perfectly reminded him of his life at its darkest point that he’d wanted to keep it, though the old memory was painful. To him, the existence of this devastated landscape meant that someone else had once understood.

“When he knew what he had become, he rebelled against it. He tried to destroy himself. But that’s not easily done.”

“How?” she gasped.

I kept my eyes on the evocative emptiness of the painting as I described Carlisle’s suicide attempts.

“He jumped from great heights. He tried to drown himself in the ocean… but he was young to the new life, and very strong. It is amazing that he was able to resist… feeding”—I glanced quickly at her but she was staring at the painting—“while he was still so new. The instinct is more powerful then, it takes over everything. But he was so repelled by himself that he had the strength to try to kill himself with starvation.”

“Is that possible?” she whispered.

“No, there are very few ways we can be killed.”

She opened her mouth to ask the most obvious follow-up, but I spoke quickly to distract her.

“So he grew very hungry, and eventually weak. He strayed as far as he could from the human populace, recognizing that his willpower was weakening, too. For months he wandered by night, seeking the loneliest places, loathing himself.…”

I described the night he found another way to live, the compromise of animal blood, and his recovery to a rational creature. Then leaving for the continent—

“He swam to France?” she interrupted, disbelieving.

“People swim the Channel all the time, Bella,” I pointed out.

“That’s true, I guess. It just sounded funny in that context. Go on.”

“Swimming is easy for us—”

“Everything is easy for you,” she complained.

I smiled at her, waiting to be sure she was done.

She frowned. “I won’t interrupt again, I promise.”

My smile widened, knowing what her reaction would be to the next bit.

“Because, technically, we don’t need to breathe.”

“You—”

I laughed and put one finger against her lips. “No, no, you promised. Do you want to hear the story or not?”

Her lips moved against my touch. “You can’t spring something like that on me, and then expect me not to say anything.”

I let my hand fall to rest against the side of her neck.

“You don’t have to breathe?”

I shrugged. “No, it’s not necessary. Just a habit.”

“How long can you go… without breathing?”

“Indefinitely, I suppose; I don’t know.” The longest I’d ever gone was a few days, all of it underwater. “It gets a bit uncomfortable—being without a sense of smell.”

“A bit uncomfortable,” she repeated in a fragile voice, barely over a whisper.

Her eyebrows were drawn together, her eyes narrowed, her shoulders rigid. The exchange, which had been funny to me a moment before, was abruptly humorless.

We were so different. Though we’d once belonged to the same species, we shared only a few superficial traits now. She must finally feel the weight of the distortion, the distance between us. I lifted my hand from her skin and dropped it to my side. My alien touch would only make that gap more obvious.

I stared at her troubled expression, waiting to see if this would be one truth too many. After a few long seconds, the stress in her features eased. Her eyes focused on my face, and a different kind of unease marked hers.

She reached up with no hesitation to press her fingers against my cheek. “What is it?”

Concern for me again. So apparently this wasn’t the too much I’d been fearing.

“I keep waiting for it to happen.”

She was confused. “For what to happen?”

I took a deep breath. “I know that at some point, something I tell you or something you see is going to be too much. And then you’ll run away from me, screaming as you go.” I tried to smile at her, but I didn’t do a very good job. “I won’t stop you. I want this to happen, because I want you to be safe. And yet, I want to be with you. The two desires are impossible to reconcile.…”

She squared her shoulders, her chin jutted out. “I’m not running anywhere,” she promised.

I had to smile at her brave façade. “We’ll see.”

“So, go on,” she insisted, scowling a little at my doubtful response. “Carlisle was swimming to France.”

I measured her mood for one more second, then turned back to the gallery. This time I pointed her toward the most ostentatious of all the paintings, the brightest, the most garish. It was meant to be a portrayal of the final judgment, but half the thrashing figures seemed to be involved in some kind of orgy, the other half in a violent, bloody combat. Only the judges, suspended above the pandemonium on marble balustrades, were serene.

This one had been a gift. It wasn’t something Carlisle would have ever picked out for himself. But when the Volturi had pressed upon him the souvenir of their time together, it wasn’t as if he could have said no.

He had some affection for the gaudy piece—and for the distant vampire overlords depicted in it—so he kept it with his other favorites. They had been very kind to him in many ways, after all. And Esme liked the small portrait of Carlisle hidden in the midst of the mayhem.

While I explained Carlisle’s first few years in Europe, Bella stared at the painting, trying to make sense of all the figures and swirling colors. I found my voice becoming less casual. It was hard to think of Carlisle’s quest to subdue his nature, to become a blessing to mankind rather than a parasite, without feeling again all the awe his journey deserved.

I’d always envied Carlisle’s perfect control but, at the same time, believed it was impossible for me to duplicate. I realized now that I’d chosen the lazy way, the path of least resistance, admiring him greatly, but never putting in the effort to become more like him. This crash course in restraint that Bella was teaching me might have been less fraught if I’d worked harder to improve in the last seven decades.

Bella was staring at me now. I tapped the relevant scene in front of us to refocus her attention on the story.

“He was studying in Italy when he discovered the others there. They were much more civilized and educated than the wraiths of the London sewers.”

She concentrated on the tableau I indicated, and then laughed suddenly, a little shocked. She’d recognized Carlisle despite the robe-like costume he was painted in.

“Solimena was greatly inspired by Carlisle’s friends. He often painted them as gods. Aro, Marcus, Caius.” I gestured to each as I said their names. “Nighttime patrons of the arts.”

Her finger hesitated just above the canvas. “What happened to them?”

“They’re still there. As they have been for who knows how many millennia. Carlisle stayed with them only for a short time, just a few decades. He greatly admired their civility, their refinement, but they persisted in trying to cure his aversion to ‘his natural food source,’ as they called it. They tried to persuade him, and he tried to persuade them, to no avail. At that point, Carlisle decided to try the New World. He dreamed of finding others like himself. He was very lonely, you see.”

I touched only lightly on the following decades, as Carlisle struggled with his isolation and finally began to consider a course of action. The story turned more personal, and also more repetitive. She’d heard some of this before: Carlisle finding me on my deathbed and making the decision that had changed my destiny. And now, that decision was affecting Bella’s destiny, too.

“And so we’ve come full circle,” I concluded.

“Have you always stayed with Carlisle, then?” she asked.

With unerring instinct, she’d found the one question I least wanted to answer.

“Almost always,” I answered.

I placed my hand on her waist to guide her out of Carlisle’s office, wishing I could also guide her away from this train of thought. But I knew she was not going to let that stand. Sure enough…

“Almost?”

I sighed, unwilling. But honesty must take precedence over shame. “Well,” I confessed, “I had a typical bout of rebellious adolescence—about ten years after I was born, created, whatever you want to call it. I wasn’t sold on his life of abstinence, and I resented him for curbing my appetite. So I went off on my own for a time.”

“Really?” Her intonation was not what I expected. Rather than being disgusted, she sounded eager to hear more. This didn’t match her reaction in the meadow, when she’d seemed so surprised that I was guilty of murder, as though that truth had never occurred to her. Perhaps she’d grown used to the idea.

We started up the stairs. Now she seemed indifferent to her surroundings; she only watched me.

“That doesn’t repulse you?” I asked.

She considered that for half a second. “No.”

I found her answer upsetting. “Why not?” I nearly demanded.

“I guess… it sounds reasonable?” Her explanation ended on a higher pitch, like a question.

Reasonable.I laughed, the sound too harsh.

But instead of telling her all the ways it was neither reasonable nor forgivable, I found myself giving a defense.

“From the time of my new birth, I had the advantage of knowing what everyone around me was thinking, both human and nonhuman alike. That’s why it took me ten years to defy Carlisle. I could read his perfect sincerity, understand exactly why he lived the way he did.”

I wondered if I would ever have gone astray if I had not met Siobhan and others like her. If I hadn’t been aware that every other creature like myself—we’d not yet stumbled across Tanya and her sisters—thought the way Carlisle lived was ludicrous. If I had only known Carlisle, and never discovered another code of conduct, I think I would have stayed. It made me ashamed that I’d let myself be influenced by others who were never Carlisle’s equals. But I’d envied their freedom. And I’d thought I would be able to live above the moral abyss they all sank to. Because I was special. I shook my head at the arrogance.

“It took me only a few years to return to Carlisle and recommit to his vision. I thought I would be exempt from the depression that accompanies a conscience. Because I knew the thoughts of my prey, I could pass over the innocent and pursue only the evil. If I followed a murderer down a dark alley where he stalked a young girl—if I saved her, then surely I wasn’t so terrible.”

There were a great many humans I’d saved this way, and yet, it never seemed to balance out the tally. So many faces flashed through my memories, the guilty I’d executed and the innocents I’d saved.

One face lingered, both guilty and innocent.

September 1930. It had been a very bad year. Everywhere, the humans struggled to survive bank failures, droughts, and dust storms. Displaced farmers and their families flooded cities that had no room for them. At the time, I wondered whether the pervasive despair and dread in the minds around me were a contributing factor to the melancholy that was beginning to plague me, but I think even then I knew that my personal depression was wholly due to my own choices.

I was passing through Milwaukee, as I’d passed through Chicago, Philadelphia, Detroit, Columbus, Indianapolis, Minneapolis, Montreal, Toronto, city after city, and then returned, over and over again, truly nomadic for the first time in my life. I never strayed farther south—I knew better than to hunt near that hotbed of newborn nightmare armies—nor farther east, as I was also avoiding Carlisle, less for self-preservation and more out of shame in that case. I never stayed more than a few days in any one place, never interacted with the humans I wasn’t hunting. After more than four years, it had become a simple thing to locate the minds I sought. I knew where I was likely to find them, and when they were usually active. It was disturbing how easy it was to pinpoint my ideal victims; there were so many of them.

Perhaps that was part of the melancholy, too.

The minds I hunted were usually hardened to all human pity—and most other emotions besides greed and desire. There was a coldness and a focus that stood out from the normal, less dangerous minds around them. Of course, it had taken most of them some time to reach this point, where they saw themselves as predators first, and anything else second. So there was always a line of victims I had been too late to save. I could only save the next one.

Scanning for such minds, I was able to tune out everything more human for the most part. But that evening in Milwaukee, as I moved quietly through the darkness—strolling when there were witnesses, running when there were not—a different kind of mind caught my attention.

He was a young man, poor, living in the slums on the outskirts of the industrial district. He was in a state of mental anguish that intruded upon my awareness, though anguish was not an uncommon emotion in those days. But unlike the others who feared hunger, eviction, cold, sickness—want in so many forms—this man feared himself.

I can’t. I can’t. I can’t do this. I can’t. I can’t.It was like a mantra in his head, repeating endlessly. It never resolved into anything stronger, never became I won’t. He thought the negatives, but meanwhile he was planning.

The man hadn’t done anything… yet. He had only dreamed of what he wanted. He had only watched the girl in the tenement up the alley, never spoken to her.

I was a bit flummoxed. I had never condemned anyone to death whose hands were clean. But it seemed likely this man would not have clean hands for long. And the girl in his mind was just a young child.

Unsure, I decided to wait. Perhaps he would overcome the temptation.

I doubted it. My recent study of the basest of human natures had left little room for optimism.

Down the alley where he lived, where the buildings leaned precariously together, there was a narrow house with a recently collapsed roof. No one could get to the second floor safely, so that was where I hid, motionless, while I listened through the next several days. Examining the thoughts of the people crowded into the sagging buildings, it didn’t take me long to find the child’s thin face in a different, healthier set of thoughts. I found the room where she lived with her mother and two older brothers and watched her through the day. This was easy; she was only five or six and so didn’t wander far. Her mother called her back when she rambled out of sight; Betty was her name.

The man watched, too, when he wasn’t scouring the streets for day labor. But he kept his distance from her in the daytime. It was at night that he paused outside the window, hiding in the shadows while a single candle burned in her family’s room. He marked at what time the candle was blown out. He noted the location of the child’s bed—just a newspaper-stuffed cushion under the open window. It was getting cool at night, but the smells in the overcrowded house were unpleasant. Everyone kept their windows open.

I can’t do this. I can’t. I can’t.His mantra continued, but he began to prepare. A piece of rope he found in a gutter. Some rags he plucked off a clothesline during his nighttime surveillance that would work as a gag. Ironically, he chose the same dilapidated house where I hid to store his collection. There was a cave-like space under the collapsed stairs. This was where he would bring the child.

Still I waited, unwilling to punish before I was positive of the crime.

The hardest part, the part he struggled with, was that he knew he would have to kill her afterward. This was distasteful, and he didn’t like to consider the how of it. But this qualm, too, was overcome. It took another week.

By this time, I was quite thirsty, and bored with the repetition in his mind. However, I knew I could not justify my own murders unless I was acting within the rules I’d created for myself. Punish only the guilty, only those who would grievously harm others if they were spared.

I was oddly disappointed the night he came for his ropes and gags. Against reason, I’d hoped he would stay guiltless.

I followed him to the open window where the child slept. He didn’t hear me behind him, would not have seen me in the shadows if he had turned. The chanting in his head was over. He could, he had realized. He could do this.

I waited until he reached through the window, until his fingers brushed her arm, looking for a good hold.…

I grabbed him by the neck and leaped to the roof three stories up, where we landed with a low thud.

Of course he was terrified by the ice-cold fingers wrapped around his throat, bewildered by the sudden flight through the air, confused as to what was happening. But when I spun him to face me, somehow he understood. He didn’t see a man when he looked at me. He saw my empty black eyes, my death-pale skin, and he saw judgment. Though he didn’t come close to guessing what I actually was, he was absolutely correct about what was happening.

He realized that I had saved the child from him, and he was relieved. Not hardened like the others, not cold and sure.

I didn’t, he thought as I lunged. The words were not a defense. He was glad he had been stopped.

He had been my only technically innocent victim, the one who had not lived to become the monster. Ending his progression toward evil had been the right thing, the only thing to do.

As I considered them all, every one of those I’d executed, I didn’t regret any of their deaths individually. The world was a better place for each one of their absences. But somehow this didn’t matter.

And in the end, blood was just blood. It quenched my thirst for a few days or weeks, and that was all. Though there was physical pleasure, it was too marred by the pain of my mind. Stubborn as I was, I could not avoid the truth. I was happier without human blood.

The total sum of death became too much for me. It was only a few months later that I gave up on my selfish crusade, gave up trying to find something meaningful in the slaughter.

“But as time went on,” I continued, wondering how much she’d intuited that I hadn’t said, “I began to see the monster in my eyes. I couldn’t escape the debt of so much human life taken, no matter how justified. And I went back to Carlisle and Esme. They welcomed me back like the prodigal. It was more than I deserved.” I remembered their arms around me, remembered the joy in their minds when I returned.

The way she looked at me now was also more than I deserved. I supposed my defense had worked, no matter how weak it sounded to me. But Bella must have been used to making excuses for me by now. I couldn’t imagine how else she could bear to be around me.

We’d reached the last door along the hallway.

“My room,” I informed her as I held it open.

I expected her reaction. The close scrutiny returned. She analyzed the view of the river, the abundance of shelving for my music, the stereo, the lack of traditional furniture, her eyes skipping from one detail to the next. I wondered if it was as interesting to her as her room had been to me.

Her eyes lingered on the wall treatments.

“Good acoustics?”

I laughed and nodded, then turned on the sound system. Even as low as the volume was, the speakers hidden in the walls and ceiling made it sound like we were in a concert hall with the performers. She smiled, then wandered over to the closest shelf of CDs.

It felt surreal to see her in the center of a space that was almost always an isolated retreat. We’d spent most of our time together in the human world—school, town, her home—and it had always made me feel the interloper, the one who didn’t belong. Less than a week ago, I couldn’t have believed she would ever be so relaxed and comfortable in the middle of my world. She was no interloper; she belonged perfectly. It was as if the room had never been complete till now.

And she was here under no pretext. I’d told no lies, revealed every one of my sins. She knew it all, and still wanted to be in this room, alone with me.

“How do you have these organized?” she wondered, trying to make sense of my collection.

My mind was so caught up in the pleasure of having her here, it took me a second to respond.

“Ummm, by year, and then by personal preference within that frame.”

Bella could hear the abstraction in my voice. She glanced up at me, trying to understand why I was staring at her so intently.

“What?” she asked, her hand straying self-consciously to her hair.

“I was prepared to feel… relieved. Having you know about everything, not needing to keep secrets from you. But I didn’t expect to feel more than that. I like it. It makes me… happy.”

We smiled together.

“I’m glad,” she said.

It was easy to see she was telling nothing but the truth. There were no shadows in her eyes. It brought her as much pleasure to be in my world as being in hers brought me.

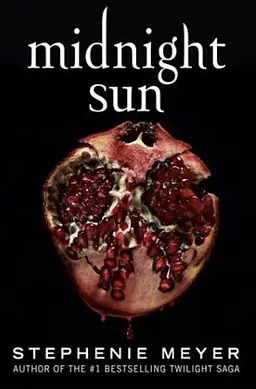

A flicker of unease twisted my expression. I thought of pomegranate seeds for the first time in a while. It felt right to have her here, but was that just my selfishness blinding me? Nothing had scared her away from me, but that didn’t mean that she shouldn’t be frightened. She’d always been too brave for her own good.

Bella watched my face change. “You’re still waiting for the running and the screaming, aren’t you?”

Close enough. I nodded.

“I hate to burst your bubble,” she said, her voice blasé, “but you’re really not as scary as you think you are. I don’t find you scary at all, actually.”

It was a well-performed lie, especially considering her usual lack of success with deception, but I knew she made the joke mostly to keep me from feeling dejected or worried. Though I sometimes regretted the depth of her leniency toward me, it did shift my mood. It was a funny joke, and I couldn’t resist playing along.

I smiled, showing too much of my teeth. “You really shouldn’t have said that.”

She’d asked to see me hunt, after all.

I coiled into a parody of my actual hunting stance, a loose, playful version. Exposing even more of my teeth, I growled softly; it was almost a purr.

She started to back away, though there was no real fear on her face. At least, no fear of physical harm. She did look a little afraid that she was about to become the butt of her own joke.

She swallowed loudly. “You wouldn’t.”

I sprang.

She wasn’t able to see much of the action; I moved at immortal speed.

Launching myself across the room, I scooped her up into my arms as I flew by. I shaped myself into a sort of defensive armor around her, so that when we collided with the sofa, she felt none of the impact.

By design, I’d landed on my back. I held her against my chest, still curled within my arms. She seemed a little disoriented, as though she wasn’t sure which way was up. She struggled to sit, but I wasn’t finished making my point.

She tried to glare at me, but her eyes were too wide to make the expression effective.

“You were saying?” I asked, my voice a playful snarl.

She tried to catch her breath. “That you are… a very, very… terrifying monster.”

I grinned at her. “Much better.”

Alice and Jasper were bounding up the stairs. I could hear Alice’s eagerness to offer an invitation. She was also very curious about the sounds of a struggle emanating from my room. She hadn’t been watching me, so now she only saw what she would find when they arrived; the way we’d gotten so disarranged was already in the past.

Bella was still trying to free herself.

“Um, can I get up now?”

I laughed at her continued breathlessness. Despite her overconfidence, I’d still been able to truly startle her.

“Can we come in?” Alice asked from the hallway, aloud for Bella’s sake.

I sat up, now holding Bella on my lap. There was no need to pretend here, though I assumed a more respectful distance would be necessary in front of Charlie.

Alice was already walking into the room as I answered, “Go ahead.”

While Jasper hesitated in the doorway, she settled herself in the middle of my rug, a wide grin on her face. “It sounded like you were having Bella for lunch, and we came to see if you would share,” she teased.

Bella braced herself, her eyes flying to my face for reassurance. I smiled and pulled her tighter against my chest.

“Sorry, I don’t believe I have enough to spare.”

Jasper followed her into the room, unable to help himself. The emotions inside were nearly intoxicating to him. In this moment, I knew Bella’s feelings were just the same as mine, for there was no counterbalance to the atmosphere of bliss that Jasper was getting high on now.

“Actually,” he said, changing the subject. I could see that he wanted to control what he was feeling, to regulate it. The ambience was overwhelming. “Alice says there’s going to be a real storm tonight, and Emmett wants to play ball. Are you game?”

I paused, looking to Alice.

Lightning fast, she ran through a few hundred images from that possible future. Rosalie was absent, but Emmett wouldn’t miss a game. Sometimes his team won, sometimes mine did. Bella was there watching, her face delighted by the otherworldly display.

“Of course you should bring Bella,” she encouraged, knowing me well enough to understand my hesitation.

Oh.Jasper was caught off guard. Internally, he readjusted his idea of what was to come. He would not be able to relax, as he’d planned. But experiencing the emotions Bella and I made each other feel… that was a trade he could accept.

“Do you want to go?” I asked Bella.

“Sure,” she answered quickly. And then after a tiny pause, “Um, where are we going?”

“We have to wait for thunder to play ball,” I explained. “You’ll see why.”

Her concern was more obvious now. “Will I need an umbrella?”

I laughed that this was her worry, and Alice and Jasper joined in.

“Will she?” Jasper asked Alice.

Another flash of images, this time tracking the course of the storm.

“No. The storm will hit over town. It should be dry enough in the clearing.”

“Good, then,” Jasper said. He found that he was excited by the idea of spending more time with Bella and me. His enthusiasm spread out from his body, infecting the rest of us. Bella’s expression changed from cautious to eager.

Cool, Alice thought, glad that her plan was now certain. She wanted recreational time with Bella, too. I’ll leave you to sort out the details.

“Let’s go see if Carlisle will come,” she said, bouncing up from the floor.

Jasper poked her in the ribs. “Like you don’t already know.”

She was out the door in the same breath. Jasper followed more slowly, savoring each second near us. He paused to shut the door behind himself, an excuse to linger that much longer.

“What will we be playing?” Bella asked as soon as the door was closed.

“You will be watching. We will be playing baseball.”

She looked at me skeptically. “Vampires like baseball?”

I answered her with put-on gravitas. “It’s the American pastime.”