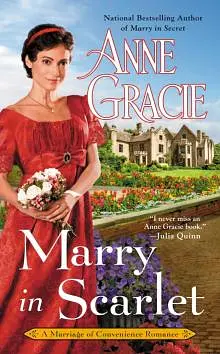

by Anne Gracie

She jumped. “Stop that. It’s—it’s distracting.”

“Distracting? I’m not distracted,” he lied. Having her so close, soft and relaxed, that velvety nape just inches from his fingertips—it was pure enticement. But she was all look but don’t touch.

“You’re distracting me.”

“Oh, you. You dislike it when I do this, do you?” He stroked her nape again.

She shivered and hunched her shoulders as if to dislodge his hand. “I said, it’s distracting.” So, she didn’t dislike it, she just found it distracting.

He hid a smile. “Good.” Her transparent honesty, her unwillingness to lie, even on such a subject—especially on such a subject—delighted him. The number of women he’d known who’d claimed his every touch, his every move was ecstasy, even as they feigned pleasure . . . And here was his prickly little George, wishing to pretend otherwise but unable to lie.

She turned her head indignantly. “Good?”

“As long as you don’t dislike it . . . Now, tell me about Martha.”

“Not until you remove your hand.”

He moved it down to her arm and started to stroke the silky skin in the inside of her elbow.

“Stop that. Put your hands in your lap,” she ordered.

He placed his hands in his lap. “So, Martha?”

Her expression softened. “Martha is a dear. She was the closest thing I had to a mother, growing up. She began as my nursemaid, and later became my cook and housekeeper. But she was always more than that. She taught me my manners, taught me my letters, taught me everything—did her best to make me a lady, even though I resisted all the way. But unsatisfactory though I was, she never stopped loving me. Even when the money ran out and there was nothing for food, let alone wages, she stayed with me.”

“No money for food?”

She shrugged. “I don’t know why the allowance from my father stopped—it was long before he died—but it did. Perhaps he thought I was old enough to support myself—I was sixteen. We had no way of contacting him, but we managed. We grew vegetables and there were eggs, and of course I hunted.”

“Hunted? But I thought you objected to—”

“I object to hunting foxes for sport. Hunting rabbits and hares for the pot is different. It was a necessity.”

So this “useless girl” had staved off starvation by hunting to keep herself and her servant alive. Her father deserved a thrashing. Pity he was dead; Hart would have liked to deliver the thrashing himself.

A thought occurred to him. “If you were so short of money, how did you acquire that stallion of yours?”

She dimpled, and said in a suspiciously airy voice, “I had rich neighbors, and some of them were, let us say, careless with their horses.”

“You stole that horse?”

“No!” Her expression was part guilt, part glee. “Not exactly. My grandfather left one good mare—a beautiful Arabian called Juno—originally bought for my mother, so the mare was mine. She was a lovely creature, getting on in years but still able to bear progeny. She came into season at the very same time the rich and careless guest of one of my neighbors left his stallion out in the paddock while he went off with friends . . .”

“You put your mare in with the stallion?”

She wrinkled her nose. “Not exactly. But I did put her in the next paddock and let nature take its course. The stallion jumped the fence, of course. I returned him to his paddock afterward, and nobody knew what had taken place. But as I’d hoped, he got a colt on Juno. Sultan was her last foal.” She slid him a glance that was part guilt, part triumph. “I know it wasn’t very ethical, but you should have seen how carelessly this fellow treated his horse. And he had the worst seat I’ve ever seen. He didn’t deserve such a fine animal.”

Hart shrugged. He had no issue with a stallion jumping a fence to reach a mare in season. He knew exactly how that stallion felt.

“So when you were so hard up, why didn’t you sell Sultan? You could have sold the animal for a good sum.” Her answer should have surprised him, but it didn’t.

“Sell Sultan? I couldn’t. When he was born, I helped deliver him—Juno had a difficult birth—and I raised him and trained him. He’s family.”

Of course he was. Dog, stallion, elderly servant—Lady Georgiana Rutherford’s family. Until the last year, apparently, when she’d discovered her real family . . .

“Now it’s my turn,” she said.

Hart frowned. “Turn for what?” He knew perfectly well what.

“To ask you about your life.”

“There’s nothing to tell. Childhood spent at Everingham Abbey, my family seat; then school, Harrow, followed by Cambridge; and you know the rest.”

She gave him a stern look. “I don’t know the rest—and as a life story, that was pathetic. I gave you details, stories, people. Tell me what you did as a child, who you cared about, what you learned.”

“There’s nothing to tell. It was all very conventional, very dull. Oh, look. London. We’re almost there.”

She peered out the window. The carriage had just reached the top of a slight hill and the city of London was spread out in the distance. For a few moments she gazed at the view, picking out the features, no doubt. But then she turned back to him. “There’s still plenty of time to tell me about your childhood. Or school—tell me about your schooling. Did you enjoy it or did you hate it?”

“Neither. I did what I had to.”

She made a frustrated sound. “You are a terrible storyteller! And you’re not playing fair.”

He shrugged. “You’re the one who wanted to play ‘let’s get to know each other.’” He loathed stirring up the past.

“Yes. Each other.” She folded her arms, fixed him with a look that was heavy with expectation and waited.

“Very well, then, I met my best friend, Sinc—Johnny Sinclair—on the first day of school. We’ve been friends ever since.”

She waited, and when it was clear he didn’t intend to say any more, she made a huffing sound and turned back to the view out of the window.

They passed the last few miles in silence. She was annoyed with him, and he understood why, but it wasn’t going to make him open his budget about things better left in the past. All this cozy exchange of stories, it wasn’t for him.

And it wasn’t necessary for marriage. A man and wife met in the bedroom and that was all that was required—at least in the kind of marriage he intended to have.

* * *

* * *

“He was hopeless, Emm. As talkative as a . . . a post. He dug so much out of me—and I tried to be honest with him and shared. And it wasn’t easy. But when it was his turn, he told me nothing—nothing personal at any rate. He just pokered up and looked down his nose and shared precisely nothing. Except that he’d met his friend, Mr. Sinclair, at school. Which everyone knows anyway.”

George squirmed now at the shameful things she’d revealed about herself; her loneliness growing up, the scorn of the villagers—he had experienced for himself the attitude of the local gentry toward her—the fact that she and Martha had been so poor they almost starved, the unethical acquisition of Sultan. She wished she could take it all back, but it was too late now.

They were in Emm’s bedchamber. Emm had finished feeding baby Bertie, and now held him against her shoulder, rubbing his back. “Do I take it that you no longer detest the duke?”

“I want to strangle him.”

Emm laughed. “That’s not quite the same thing. I occasionally want to strangle Cal, but I love him dearly all the same.”

George pondered the question. She’d definitely softened toward the duke. A bit. His kisses drove her wild, but that wasn’t it. She mightn’t be in season like a mare or a cat—though she was still sure that something was going on—but liking, respect or love had nothing to do with physical des

ire—she knew that much. Men were like stallions, only on two legs. They’d jump a fence for a filly they fancied.

She’d been angry that he’d come chasing down to Bath after her but . . . though jealousy was unattractive, it at least showed he cared, even if he didn’t trust her. And with a mother like his . . .

Actually, that was when she’d started to soften toward him first, when he realized how his mother had deceived and manipulated her. He could have left it, not exposed the lie—it would have made it easier for him—but he hadn’t. He realized she’d given her promise based on a false premise and he’d taken her to see for herself what his mother had done.

And then he’d offered to release her. Despite all his efforts to entrap her. He’d played fair, shown her a side of him she hadn’t suspected—an honorable streak.

And then, when she’d told him he was just like his mother, just as ruthlessly manipulative—well, he had every right to be furious with her. She wouldn’t have been surprised if he’d denied it, and refused to give her opinion any credence at all.

But he hadn’t. He’d listened, he’d thought about it. And he’d taken it on the chin—and later he’d apologized.

That was probably the moment she’d looked at him, really looked at him, past the haughty manner and the cold arrogance, and glimpsed the possibility of another man.

The baby belched loudly, startling George. She didn’t think such a tiny thing could make such a sound. “What a clever boy you are,” Emm murmured as she placed him on his back on the bed beside her. He lay quietly among the pillows, staring intently at the world around him with bright, dark blue eyes. He waved a little hand and George slipped a finger in it, smiling as he gripped her firmly.

“Just because a convenient marriage is arranged,” Emm said, “it doesn’t mean that’s how it will continue.”

George said nothing. She played with the baby’s hand. She’d seen plenty of marriages where the husband and wife might as well be strangers, for all the concern they showed for each other.

Emm continued, “When I married your uncle, there was no talk of love—it was a purely practical arrangement. He wanted someone to take care of—and control—you three girls, and I, I wanted security, a home and the chance of having a child of my own.”

George looked up. “But you’re in love with Cal, aren’t you? And he with you?”

Emm smiled. “Oh, yes, but that came afterward. And that’s what I want you to think about. Try to keep your mind open about the duke. I know you think he’s arrogant and cold and—”

“He is.” But George knew now that wasn’t all he was.

“Yes, but think back to how Cal was when you first met him. Was he not arrogant, bossy, infuriating?”

“He most certainly was.”

“So what changed? Did Cal change? Or did you?”

George thought about it. Cal was still pretty arrogant, and very bossy at times—only not with Emm. He’d been downright hostile toward Rose’s long-lost husband . . . until he decided that Thomas was all right. That Thomas could be trusted.

He was being protective of Rose, and she couldn’t really fault him for that.

As for how he treated George, they’d started off badly when he more or less kidnapped her, but now she thought about it, he’d softened quite a bit toward her, and in fact had championed her on a number of occasions, particularly with Aunt Agatha.

“You’ve begun to let the duke get to know you—that’s a good start. And if he’s reluctant to open up himself, persist, but gently,” Emm said. “Some men find it very difficult to reveal the softer side of themselves, to let themselves be vulnerable.”

“Vulnerable?” George couldn’t imagine the duke being the slightest bit vulnerable to anyone or anything. He only wanted her to feel vulnerable.

“Vulnerable to love. Cal was as tightly bound up against letting himself love as any man could be. He didn’t have an easy time as a young boy, losing his mother and being rejected by his father’s second wife. And then there were his years in the army, where a man has to arm himself against the softer emotions simply to survive. He was out of the habit of even thinking about love. It simply never occurred to him. And if you recall, it took the rather drastic action of someone shooting me to shock Cal into the realization that he loved me.” She smiled. “I, of course, knew a long time before that that I loved him. But even so, it was a nerve-racking realization.”

“Nerve-racking? For you?”

“Oh, yes. After years as a spinster, never expecting to love or be loved, to marry or to have a child, I had to open myself to the frightening possibility of love. And with that came the equally terrifying possibility of rejection. And of making a fool of myself, and earning my husband’s scorn—he’d made an intensely practical marriage, recall, not a love match.”

George was silent. She hadn’t really thought of it like that. It had seemed inevitable to her that Emm and Cal should be in love; but now, looking back, and in the light of Emm’s explanation, she could see that it wasn’t so simple.

And that she had more in common with Emm than she realized.

Emm leaned forward and smoothed a stray curl back from George’s face. “Men aren’t the only people who find it hard to open up to someone else.”

George grimaced. “You mean me, I suppose.”

“I mean all of us. Love takes a leap of faith. It’s an act of courage.”

Her words hung in the air. Little Bertie gave a half-hearted wail, and his mother picked him up and began to wrap him in his soft baby blanket. “You have a lot of love to give, George, dear. You give it unstintingly to those closest to you—Rose, Lily, Cal and me, your Martha, Finn, and”—she kissed the baby—“to little Bertie here. You’re a loving person, and loyal to the backbone.”

George felt her cheeks heating. She never knew how to take compliments. And talking about emotions made her uncomfortable. “What’s the ‘but’?”

“No ‘but,’ I’m just reminding you that you are a prize to be won.”

George didn’t feel like much of a prize—nobody had ever thought of her as a prize—but Emm’s words warmed her.

“And the duke has gone to a lot of trouble to win you.”

“Win me? He trapped me.”

“Perhaps, in his mind, it’s the same thing.”

George scowled. It wasn’t the same thing at all. But he’d offered to release her and for some stupid reason she didn’t fully understand yet—midsummer madness?—she’d agreed to honor the betrothal.

“And you have always had a particular soft spot for wounded creatures. Think about that when you look at your duke.”

“The duke? A wounded creature? Don’t make me laugh.”

“You’ve met his mother, haven’t you?”

George stilled.

Emm added, “We are all wounded creatures in one way or another—Cal, me, Rose, Thomas, Lily, Edward, the aunts and you—yes, you, dear George. The duke has his points of vulnerability, as we all do, and manlike, he’ll do his best to conceal them from the world—and you. So think about it.”

George tried to think of the duke as a wounded creature, but failed. He was a predator. One who took more than he gave. Wasn’t he?

Chapter Sixteen

There are very few of us who have heart enough to be really in love without encouragement.

—JANE AUSTEN, PRIDE AND PREJUDICE

George was having the final fitting of her wedding dress. It was spectacular, but she had to admit she had an occasional qualm about wearing it, now that first angry impulse had passed.

Miss Chance pinned the last tiny alteration in place, stepped back and eyed her critically. “I must admit, Lady George, I had me doubts when you first chose this fabric, but you were right. It’s stunnin’.”

Stunning? In what sense? George wondered as she gazed at her image in t

he looking glass. Shocking or beautiful? She’d chosen it to be shocking, but she had to admit the color did suit her.

She’d chosen it to shock, to defy all those harridans who’d twitted her about entrapment and implied she was a money-grubbing, title-snatching, hypocritical strumpet.

And to remind the duke who’d entrapped whom.

“I’ll finish off those last little bits and send it around this afternoon,” Miss Chance said. “Now, your maid knows what to do with it?”

Sue nodded eagerly. Miss Chance’s assistants had given her thorough instructions about how to care for a silk dress.

George was pleased she’d taken only Sue with her to the dressmaker. Lily and Rose and their husbands were on their way to London, and she didn’t want them—didn’t want anyone—to see the dress until her wedding day.

The day finished with a visit from Aunt Agatha. George almost refused to see her—she was still angry about the way Aunt Agatha had helped the duke’s mother to deceive her. But she was about to get married; it was time to put past grudges behind her. Aunt Agatha, meddling old woman that she was, was still family. And according to Aunt Dottie, she meant well.

“I have some words of advice regarding your marriage,” Aunt Agatha announced. George sighed, sat down and pretended to listen.

“Men are animals,” Aunt Agatha declared. “They will lie down with females of all kinds—young, old, pretty, plain, aristocratic or plebeian—it makes little difference to them. But the act is not in any way important to them—and should not be to their wives. It’s merely an itch they have to scratch.”

George kept a polite expression on her face. An itch to scratch indeed.

The old lady continued, “Ladies, on the other hand, have a tendency to read more into the significance of the act, ascribing meaning and emotions to it that simply don’t exist.” She peered at George to make sure she understood. “So, protect your heart, Georgiana, protect your heart.” She gave a brisk nod and departed, leaving George staring after her.