by Julia Quinn

“Of course it does,” Tillie returned. “It’s the principle of the matter. I don’t want to get them in trouble, after all, especially while they are providing such a thoughtful blind eye.”

“Very well,” Peter said, deciding there was little point in following her logic. “Will that tree do?” He pointed to a large elm, halfway between Rotten Row and Serpentine Drive.

“Right between the two main thoroughfares?” she said, scrunching her nose. “That’s a terrible idea. Let’s go over there, on the other side of the Serpentine.”

And so they strolled, just a little bit out of sight of Tillie’s servants, but not, much to Peter’s simultaneous relief and dismay, out of sight of everyone else.

They walked for several minutes in silence, and then Tillie said, in a rather casual tone, “I heard a rumor about you this morning.”

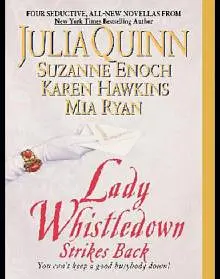

“Not something you read in Whistledown, I hope.”

“No,” she said thoughtfully, “it was mentioned this morning. By another one of my suitors.” And then, when he didn’t rise to her bait, she added, “When you didn’t call.”

“I can hardly call upon you every day,” he said. “It would be remarked upon, and besides, we had already made arrangements to meet this afternoon.”

“Your visits to my home have already been remarked upon. I hardly think one more would attract additional notice.”

He felt himself smiling—a slow, lazy grin that warmed him from the inside out. “Why, Tillie Howard, are you jealous?”

“No,” she returned, “but aren’t you?”

“Should I be?”

“No,” she admitted, “but while we’re on the subject, why should I be jealous?”

“I assure you I haven’t a clue. I spent the morning at Tattersall’s, gazing upon horses I can’t afford.”

“That sounds rather frustrating,” she commented, “and don’t you want to know what the rumor was I heard?”

“Almost as much,” he drawled, “as I suspect you wish to tell it to me.”

She pulled a face at that, then said, “I’m not one to gossip…much, but I heard that you led a somewhat wild existence when you returned to England last year.”

“And who told you this?”

“Oh, nobody in particular,” she said, “but it does beg the question—”

“It begs a great many questions,” he muttered.

“How was it,” she continued, ignoring his grunts, “that I never heard of this debauchery?”

“Probably,” he said rather starchily, “because it’s not fit for your ears.”

“It grows more interesting by the second.”

“No, it grew less interesting by the second,” he stated, in a tone meant to quell further discussion. “And that is why I’ve reformed my ways.”

“You make it sound vastly exciting,” she said with a smile.

“It wasn’t.”

“What happened?” Tillie asked, proving once and for all that any attempts he made to cow her into submission would be fruitless.

He stopped walking, unable to think clearly and move at the same time. One would think he’d have mastered the art in battle, but no, it didn’t seem to be in evidence. Not here in Hyde Park, anyway.

And not with Tillie.

It was funny—he’d been able to forget Harry for much of the past week. There had been the conversations with Lady Canby, to be sure, and the undeniable pang he felt whenever he saw a soldier in uniform, whenever he recognized the hollow shadow in their eyes.

The same shadow he’d seen so many times in the mirror.

But when he was with Tillie—it was strange, because she was Harry’s sister, and so like him in so many ways—but when he was with her, Harry was gone. Not forgotten, precisely, but just not there, not hanging over him like a guilty specter, reminding him that he was alive and Harry was not, and such it would be for the rest of his life.

But before he’d met Tillie….

“When I returned to England,” he said to her, his voice soft and slow, “it wasn’t long after Harry’s death. It wasn’t long after the death of a lot of men,” he added caustically, “but Harry’s was the one I felt most deeply.”

She nodded, and he tried not to notice that her eyes were glistening.

“I’m not really sure what happened,” he continued. “I don’t think I planned it, but it seemed so chance that I was alive and he was not, and then one night I went out with some friends, and suddenly I felt as if I had to live for both of us.”

He’d been lost for a month. Maybe a little more. He didn’t remember it well; he’d been drunk more often than not. He’d gambled money he didn’t have, and it was only through sheer luck that he hadn’t sent himself to the poorhouse. And there had been women. Not as many as there could have been, but more than there should have been, and now, as he looked at Tillie, at the woman he was quite certain he’d worship until his dying day, he felt rude and unclean, and rather like he’d made a mockery of something that should have been precious and divine.

“Why did you stop?” Tillie asked.

“I don’t know,” he said with a shrug. And he didn’t know. He’d been at a gambling hell one night and, in a moment of rare sobriety, he’d realized that all this “living” wasn’t making him happy. He wasn’t living for Harry. He wasn’t even living for himself. He was simply avoiding his future, pushing back any reason to make a decision and move forward.

He’d walked out that night and never looked back. And he realized that he must have been a bit more circumspect in his dissolution than he’d realized, because until now, no one had brought it up. Not even Lady Whistledown.

“I felt the same way,” she said softly, and her eyes held a strange, faraway softness, as if she were somewhere else, some time else.

“What do you mean?”

She shrugged. “Well, I didn’t go about drinking and gambling, of course, but after we were notified of…” She stopped, cleared her throat, and looked away before she continued. “Someone came out to our home, did you know that?”

Peter nodded, even though he hadn’t been privy to that information. But Harry was a son of one of England’s most noble houses. It stood to reason that the army would inform his family of his demise with a personal messenger.

“It was almost as if I were pretending he was with me,” Tillie said. “I suppose I was, actually. Everything I saw, everything I did, I would think to myself—What would Harry think? Or—Oh, yes, Harry would like this pudding. He’d have eaten double portions and left none for me.”

“And did you eat more or less?”

She blinked. “I beg your pardon?”

“Of the pudding,” Peter explained. “When you realized Harry would have taken your share, did you eat your portion or leave it?”

“Oh.” She stopped, thought about that. “Left it, I think. After a few bites. It didn’t seem right to enjoy it so much.”

Quite suddenly, he took her hand. “Let’s walk some more,” he said, his voice strangely insistent.

Tillie smiled at his urgency and sped her pace to match his. He walked with a long-legged stride, and she found herself nearly skipping along to keep up. “Where are we going?”

“Anywhere.”

“Anywhere?” she asked bemusedly. “In Hyde Park?”

“Anywhere but here,” he clarified, “with eight hundred people about.”

“Eight hundred?” She couldn’t help but smile. “I see but four.”

“Hundred?”

“No, just four.”

He stopped, gazing down at her with a vaguely paternal expression.

“Oh, very well,” she conceded, “maybe eight, if you’re willing to count Lady Bridgerton’s dog.”

“Are you up to a footrace?”

“With you?” she asked, her eyes widening with surprise. He was acting most odd. But it wasn’t worrisome, just amusing, really.

“I’ll give you a head start.”

“To make up for my shorter

limbs?”

“No, for your feeble constitution,” he said provokingly.

And it worked. “Now that is a lie.”

“Do you think?”

“I know.”

He leaned against a tree, crossing his arms in a most annoyingly condescending manner. “You shall have to prove it to me.”

“In front of all eight hundred onlookers?”

He quirked a brow. “I see but four. Five with the dog.”

“For a man who doesn’t like to attract attention, you’re rather pushing the edge just now.”

“Nonsense. Everyone is more than wrapped up in their own affairs. And besides, they’re all enjoying the sun too much to take notice.”

Tillie looked around. He had a point. The other people in the park—and there were considerably more than eight, although not nearly the hundreds he’d bemoaned—were laughing and joking and, all in all, acting in a most indecorous manner. It was the sun, she realized. It had to be. It had been overcast for what had felt like years, but today was one of those perfect blue-sky days, with sunshine so intense that every leaf on every tree seemed drawn more crisply, every flower painted from a more vivid palette. If there were rules to be followed—and Tillie was quite sure there were; they’d certainly been drummed into her since birth—then the ton seemed to have forgotten them this afternoon, at least the ones that governed staid behavior on a sunny day.

“All right,” she said gamely. “I accept your challenge. Where shall we race to?”

Peter pointed to a cluster of tall trees in the distance. “That tree right there.”

“The near one or the far one?”

“The middle one,” he said, clearly just to be contrary.

“And how much of a head start do I receive?”

“Five seconds.”

“Timed or counted in your head?”

“Good glory, woman, you’re a bit of a stickler.”

“I’ve grown up with two brothers,” she said with a level stare. “I’ve had to be.”

“Counted in my head,” he said. “I haven’t a watch with me in any case.”

She opened her mouth, but before she could say anything, he interjected, “Slowly. Counted slowly in my head. I have a brother, too, you know.”

“I know, and did he ever let you win?”

“Not even once.”

Her eyes narrowed. “Are you going to let me win?”

He smiled, slowly, like a cat. “Maybe.”

“Maybe?”

“It depends.”

“On what?”

“On the boon I’m to receive if I lose.”

“Isn’t one meant to receive a boon for winning?”

“Not when one throws the race.”

She gasped with outrage, then retorted, “You won’t have to throw a thing, Peter Thompson. I’ll see you at the finish line!” And then, before he could get his footing, she was off, tearing across the grass with an abandon that would surely come to haunt her the following day, when all of her mother’s friends came calling for their daily dose of tea and gossip.

But right then, with the sun shining on her face and the man of her dreams nipping at her heels, Tillie Howard could not bring herself to care.

She was fast; she’d always been fast, and she laughed as she ran, one hand pumping along, the other holding her skirt a few inches off the grass. She could hear Peter behind her, laughing as his footsteps rumbled ever closer. She was going to win; she was quite certain of that. She’d either win it fair and square, or he’d throw the race and hold it over her head for eternity, but she didn’t much care.

A win was a win, and right now Tillie felt invincible.

“Catch me if you can!” she taunted, looking over her shoulder to gauge Peter’s progress. “You’ll never—Oomph!”

The breath flew from her body with stunning speed, and before Tillie could make another sound, she was sprawled on the grass, tangled up with what was—thank heavens!—another female.

“Charlotte!” she gasped, recognizing her friend Charlotte Birling. “I’m so sorry!”

“What were you doing?” Charlotte demanded, righting her bonnet, which had gone drunkenly askew.

“A footrace, actually,” Tillie mumbled. “Don’t tell my mother.”

“I won’t have to,” Charlotte replied. “If you think she’s not going to hear of this—”

“I know, I know,” Tillie said with a sigh. “I’m hoping she’ll chalk it up to sun-induced insanity.”

“Or perhaps sun-blindness?” came a masculine voice.

Tillie looked up to see a tall, sandy-haired man she did not know. She looked to Charlotte, who quickly made introductions.

“Lady Mathilda,” Charlotte said, rising to her feet with the stranger’s help, “this is Earl Matson.”

Tillie murmured her greetings just as Peter skidded to a halt beside her. “Tillie, are you all right?” he demanded.

“I’m fine. My dress might be ruined, but the rest of me is no worse for wear.” She accepted his helpful hand and stood up. “Are you acquainted with Miss Birling?”

Peter shook his head no, and Tillie made the introductions. But when she turned to introduce him to the earl, he nodded and said, “Matson.”

“You already know each other?” Tillie queried.

“From the army,” Matson supplied.

“Oh!” Tillie’s eyes widened. “Did you know my brother? Harry Howard?”

“He was a fine fellow,” Matson said. “We all liked him a great deal.”

“Yes,” Tillie said, “everyone liked Harry. He was quite special that way.”

Matson nodded his agreement. “I’m very sorry for your loss.”

“As are we all. I thank you for your regards.”

“Were you in the same regiment?” Charlotte asked, looking from the earl to Peter.

“Yes, we were,” Matson said, “though Thompson here was lucky enough to remain through the action.”

“You weren’t at Waterloo?” Tillie asked.

“No. I was called home for family reasons.”

“I’m so sorry,” Tillie murmured.

“Speaking of Waterloo,” Charlotte said, “do you intend to go to next week’s reenactment? Lord Matson was just complaining that he missed the fun.”

“I’d hardly call it fun,” Peter muttered.

“Right,” Tillie said brightly, eager to avoid an unpleasant encounter. She knew that Peter despised the glorification of war, and she rather thought he’d not be able to remain polite to someone who was actually sorry he’d missed such a scene of death and destruction. “Prinny’s reenactment! I’d quite forgotten about it. It’s to be at Vauxhall, is it not?”

“A week from today,” Charlotte confirmed. “On the anniversary of Waterloo. I’ve heard that Prinny is beside himself with excitement. There are to be fireworks.”

“Because we want this to be an accurate representation of war,” Peter bit off.

“Or Prinny’s idea of accurate, anyway,” Matson said, his tone noticeably cool.

“Perhaps it is meant to mimic gunfire,” Tillie said quickly. “Will you go, Mr. Thompson? I should appreciate your escort.”

He paused for a moment, and she absolutely knew he didn’t want to. But even so, she could not quell her selfishness and she said, “Please. I want to see what Harry saw.”

“Harry didn’t—” He stopped, coughed. “You won’t see what Harry saw.”

“I know, but still, it’s as close as I’m to come. Please say you’ll accompany me.”

His lips tightened, but he said, “Very well.”

She beamed. “Thank you. It’s very kind of you, especially since—” She cut herself off. She didn’t need to inform Charlotte and the earl that Peter didn’t wish to attend. They might have deduced as much on their own, but Tillie didn’t need to spell it out.

“Well, we must be going,” Charlotte said, “er, before anyone—”

“We need to be on our way,”

the earl said smoothly.

“Terribly sorry about the footrace,” Tillie said, reaching out and squeezing Charlotte’s hand.

“Think nothing of it,” Charlotte replied, returning the gesture. “Pretend I’m the finish line, and then you’ve won.”

“An excellent idea. I should have thought of it myself.”

“I knew you’d find a way to win,” Peter murmured once Charlotte and the earl had wandered off.

“Was it ever in doubt?” Tillie teased.

He shook his head slowly, his eyes never leaving her face. He was watching her with an odd intensity, and she suddenly realized that her heart was beating a little too fast, and her skin was tingling, and—

“What is it?” she asked, because if she didn’t speak, she was quite certain she would forget to breathe. Something had changed in the last minute; something had changed within Peter, and she had a feeling that whatever it was, it would change her life as well.

“I need to ask you a question,” he said.

Her heart soared. Oh, yes, yes, yes! This could only be one thing. The entire week had been leading up to it, and Tillie knew that her feelings for this man were not one-sided. She nodded at him, knowing that her heart was in her eyes.

“I—” He stopped and cleared his throat. “You must know that I care for you a great deal.”

She nodded. “I had hoped,” she murmured.

“And I believe that you return my feelings?” He said it as a question, which she found absurdly touching. So she nodded again, and then threw caution to the wind and added, “Very much.”

“But you also must know that a match between the two of us is not anything that your family, or indeed, anyone, would have expected.”

“No,” she said cautiously, not certain where he was leading with this. “But I fail to see—”

“Please,” he said, cutting her off, “allow me to finish.”

She held silent, but it didn’t feel right, and her mood, which had been spinning toward the stars, took a brutal tumble back to earth.

“I want you to wait for me,” he said.

She blinked, unsure of how to interpret that. “What do you mean?”

“I want to marry you, Tillie,” he said, his voice unbearably solemn. “But I can’t. Not now.”

“When?” she whispered, hoping for two weeks, or two months, or even two years. Anything, as long as he put a date on it.