by Linda Howard

* * *

KILL AND TELL

By

Linda Howard

* * *

Contents

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

* * *

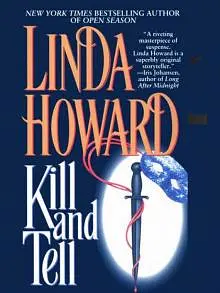

"Linda Howard is an extraordinary talent [whose] unforgettable novels [are] richly flavored with scintillating sensuality and high-voltage suspense," raves Romantic Times. Now she brings her daring touch to a seductive new thriller with an astonishing twist…

Kill and Tell

Still reeling from her mother's recent death, Karen Whitlaw is stunned when she receives a package containing a mysterious notebook from the father she has barely seen since his return from the Vietnam War over twenty years ago. Unwilling to deal with her overwhelming emotions, Karen packs the notebook away, putting it—and her father—out of her mind, until she receives a shocking phone call. Her father has been murdered on the gritty streets of New Orleans.

Homicide detective Marc Chastain considers the murder nothing more than street violence against a homeless man, and Karen accepts his judgment—at first. But she changes her mind when her home is burglarized and "accidents" begin to happen. All at once, she faces a chilling realization: whoever killed her father is now after her. Desperate for answers, Karen retrieves the only thing that links her to her father—the notebook he had sent months before. Inside its worn pages, she makes an unsettling discovery: her father had been a sniper in Vietnam and the notebook contains a detailed account of each one of his kills.

Now running for her life, Karen entrusts the book and its secrets to Marc Chastain. Together they unravel a disturbing story of politics, power, and murder—and face a killer who will stop at nothing to get his hands on the kill book.

"An incredibly talented writer… Linda Howard knows what romance readers want…"

—Affaire de Coeur

* * *

LINDA HOWARD

Kill and Tell

POCKET BOOKS

New York London Toronto Sydney Tokyo Singapore

* * *

This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places and incidents are products of the author's imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual events or locales or persons; living or dead, is entirely coincidental.

An Original Publication of POCKET BOOKS

POCKET BOOKS, a division of Simon & Schuster Inc.

1230 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10020

Copyright © 1998 by Linda Howington

ISBN: 0-671-56883-3

First Pocket Books printing January 1998

POCKET and colophon are registered trademarks of

Simon & Schuster Inc.

Cover art by Brian Bailey

Printed in the U.S.A.

* * *

This book is dedicated to John Kramer, and to cops everywhere. Thanks, John, for taking me around New Orleans, telling me the interesting stuff and showing me the interesting sights.

* * *

Kill

and

Tell

* * *

Chapter 1

^ »

February 13, Washington, D.C.

Dexter Whitlaw carefully sealed the box, securing every seam with a roll of masking tape he had stolen from WalMart the day before. While he was at it, he had also stolen a black marker, and he used it now to print an address neatly on the box. Leaving the marker and roll of tape on the ground, he tucked the box under his arm and walked to the nearest post office. It was only a block, and the weather wasn't all that cold for D.C. in February, mid-forties maybe.

If he were a congressman, he thought sourly, he wouldn't have to pay any freaking postage.

Thin winter sunshine washed the sidewalks. Earnest-looking government workers hurried by, black or gray overcoats flapping, certain of their importance. If anyone asked their occupation, they never said, "I'm an accountant," or "I'm an office manager," though they might be exactly that. No, in this town, where status was everything, people said, "I work for State," or "I work for Treasury," or, if they were really full of themselves, they used initials, as in "DOD," and everyone was expected to know that meant Department of Defense. Personally, Dexter thought they should all have IDs stating they worked for the DOB, the Department of Bullshit.

Ah, the nation's capital! Power was in the air here, perfuming it like the bouquet of some rare wine, and all these fools were giddy with it. Dexter studied them with a cold, distant eye. They thought they knew everything, but they didn't know anything.

They didn't know what real power was, distilled down to its purest form. The man in the White House could give orders that would cause a war, he could fiddle with the football, the locked briefcase carried by an aide who was always close by, and cause bombs to be dropped and millions killed, but he would view those deaths with the detachment of distance. Dexter had known real power, back in Nam, had felt it in his finger as he slowly tightened the slack on a trigger. He had tracked his prey for days, lying motionless in mud or stinging weeds, ignoring bugs and snakes and rain and hunger, waiting for that perfect moment when his target loomed huge in his scope and the crosshairs delicately settled just where Dexter wanted them, and all the power was his, the ability to give life or end it, pull the trigger or not, with all the world narrowed down to only two people, himself and his target.

The biggest thrill of his life had been the day his spotter had directed him to a certain patch of leaves in a certain tree. When his scope had settled, he had found himself looking at another sniper, Russian from the looks of him, rifle to his shoulder and scope to his eye as he tried to acquire them. Dexter was ahead of him by about a second, and he got his shot squeezed off first. One second, a heartbeat longer, and the Russian would have gotten off the first shot, and old Dexter Whitlaw wouldn't be here admiring the scenery in Washington, D.C.

He wondered if the Russian had ever seen him, if there had been a split second of knowledge before the bullet blasted out all awareness. No way he could have seen the bullet, despite all the fancy special effects Hollywood put in the movies showing just that. No one ever saw the bullet.

Dexter entered the warm post office and connected to the end of the line waiting for service at the counter. He had chosen lunch hour, the busiest time, to cut down on the chance of any harried postal clerks remembering him. Not that there was anything particularly memorable about him, except for the cold eyes, but he didn't like taking chances. Being careful had kept him alive in Nam and had worked for the twenty-five years since he had returned to the real world and left the green hell behind.

He didn't look prosperous, but neither did he look like a street bum. His coat was reversible. One side, which he now wore on the outside, was a sturdy brown tweed, slightly shabby. The other side, which he wore when he was out on the street, was patched and torn, a typical street bum's coat. The coat was good, simple camouflage. Snipers learned how to blend with their surroundings.

When his turn came, he placed the box on the counter to be weighed and fished some loose bills out of his pocket. The box was addressed to Jeanette Whitlaw, Columbus, Ohio. His wife.

He wondered why she hadn't divorced him. Hell, maybe she had; he hadn't called her in a couple of years now, maybe longer. He tried to think when was

the last time—

"Dollar forty-three," the clerk said, not even glancing at him, and Dexter laid two ones on the counter. Pocketing the change, he left the post office as unobtrusively as he had entered it.

When had he last talked to Jeanette? Maybe three years. Maybe five. He didn't pay much attention to calendars. He tried to think how old the kid would be now. Twenty? She'd been born the year of the Tet offensive, he thought, but maybe not. 'Sixty-eight or 'sixty-nine, somewhere along through there. That made her… damn, she was twenty-nine! His little girl was pushing thirty! She was probably married, with a couple of kids, which made him a grandpa.

He couldn't imagine her grown. He hadn't seen her for at least fifteen years, maybe longer, and in his mind he always pictured her as she had been at seven or eight, skinny and shy, with big brown eyes and a habit of biting her bottom lip. She had spoken to him only in whispers, and then only when he asked her a direct question.

He should've been a better daddy to her, a better husband to Jeanette. He should have done a lot of things in his life, but looking back and seeing them didn't give a man the chance to go back and change any of them. It just let him regret not doing them.

But Jeanette had kept on loving him, even when he came back from Nam so cold and distant, forever changed. In her eyes, he had remained the edgy, sharp-eyed West Virginia boy she had loved and married, never mind that the boy had died in a bug-infested jungle and the man who returned home to her was a stranger in all but face and form.

The only time he felt alive since then was when he had a rifle in his hands, sighting through the scope and feeling that rush of adrenaline, the heightening of all his senses. Funny that the thing that had killed him was the only thing that could make him feel alive. Not the rifle; the rifle, as true and faithful a tool as had ever been fashioned by man, was still just a tool. No, what made him feel alive was the skill, the hunt, the power. He'd been a sniper, a damn good one. He could have come back to Jeanette if it had been only that, he sometimes thought, though he was years past trying to analyze things.

He'd killed a lot of men, and murdered one.

The distinction was clear in his mind. War was war. Murder was something else.

He stopped at a pay phone and fished some change out of his pocket. He had already memorized the number. He fed in the change and listened to the ring. When the call was answered on the other end, he said clearly, "My name is Dexter Whitlaw."

He had wasted his life paying for the crime he had committed. Now it was someone else's turn to pick up the tab.

* * *

Chapter 2

« ^ »

February 17, Columbus, Ohio

The package was lying on the small front porch when Karen Whitlaw got home from work that February night. Her headlights flashed briefly on it as she pulled into the driveway, but she was so tired she couldn't work up any curiosity over the contents. Wearily, she lifted her tote bag, crammed full with her purse and papers and the paraphernalia of her job, and endured the usual struggle of climbing out of the car with the heavy bag. It caught on the console, then on the steering wheel; swearing under her breath, Karen jerked the bag free, and it banged painfully against her hip. She slogged through the snow to the porch, gritting her teeth as the icy mush slid down inside her shoes. She should have put on her boots, she knew, but she had been too tired when her shift ended to do anything but drive home.

The box was propped against the raised threshold, between the screen door and the front door. She unlocked the door and reached in to flip on the lights, then leaned down to lift the box. She hadn't ordered anything; the box had probably been delivered to the wrong address.

The house was chilly and silent. She had forgotten to leave a light on again that morning. She didn't like coming home to darkness; it reminded her all over again that her mother was no longer there, that she wouldn't unlock the door and smell the delicious smells of supper cooking or hear Jeanette humming in the kitchen. The television would be on even though no one was watching it, because Jeanette liked the background noise. No matter how late Karen worked or how tired she was when she got home, she had always known her mother would have a hot meal and a quick smile waiting for her.

Until three weeks ago.

It had happened fast. Jeanette had complained one morning of feeling achy and feverish and diagnosed herself as having caught a cold. She sounded a little congested, and when Karen took her temperature it was only ninety-nine degrees, so a cold seemed like a reasonable assumption. At noon, Karen called to check on her, and though Jeanette's cough was worse, she kept saying it was just a cold.

When Karen got home that night, she took one look at her mother, huddled in a blanket on the sofa and shaking with chills, and knew it was influenza instead of just a cold. Her temperature was a hundred and three. The stethoscope relayed alarming sounds to Karen's trained ears: both lungs were severely congested.

Karen had always thought the best benefit of being a nurse was learning how to bully people gently and inexorably into doing what you wanted. While Jeanette argued that she had only a cold and it was silly to go to a hospital with a cold, Karen made swift, competent preparations and within fifteen minutes had Jeanette, warmly wrapped, in the car.

It had been snowing heavily. Karen had always enjoyed snow, but now the sight of it brought back that night, when she had driven, white-knuckled, through the swirling, blinding sheets of white and listened to her mother fight an increasingly desperate battle for oxygen. She made it to the hospital where she worked, driving up to the emergency entrance and blowing the horn until help came, but other than the snow, her only clear memory of that night was of Jeanette lying on the white sheets, small and somehow shrunken, rapidly fading into unresponsiveness no matter how much Karen talked to her.

Acute viral pneumonia, the doctors said. It worked fast, shutting down all the internal organs one by one as they starved for oxygen. Jeanette died a mere four hours after arriving at the hospital, though the medical team had worked frantically in their efforts to defeat the virus.

There were so many details to dying. There were forms to fill out, forms to sign, forms to take to other people. Calls and decisions had to be made. She had to choose a funeral home, a service, a coffin, the dress her mother was to be buried in. There were people to be entertained—God!—her mother's friends who called and came over and brought more food than Karen would ever be able to eat, her own colleagues from work, a couple of neighbors. Her throat felt permanently closed, her eyes gritty. She couldn't cry in front of all those people, but at night, when she was alone, she couldn't stop crying.

She got through the funeral service, and though she had always thought them barbaric, she now understood the sense of closure ritual brought, a ceremony to mark the passing of a sweet woman who had never asked much from life, who was content with the ordinary. Prayer and song marked the end of that life and paid homage to it.

Since then, Karen had gotten through the days, but that was all. Her grief was still raw and fresh, her interest in work nonexistent. For so long, she and Jeanette had been united, the two of them against the world. First Jeanette had worked, and worked hard at any job she could get, to keep a roof over their heads and give Karen the opportunity for a good education. Then it had been Karen's turn to work and Jeanette's time to rest, to do what she enjoyed most: puttering around their small house, cooking, doing the laundry, creating the nest necessity had always denied her.

But that was gone now, and there was no getting it back. All Karen had left was this empty house, and she knew she couldn't live here much longer. Today she had taken the step of calling a real estate agent and putting the house on the market. Living in an apartment would be better than facing the empty house, and her memories, day after day after day.

The box wasn't heavy. Karen held it tucked under one arm while she closed and locked the door, then let the heavy bag slip off her shoulder onto a chair. She tilted the box toward the light to read the label.

There was no return address, but her mother's name hit her. "JEANETTE WHITLAW" was printed on the box in plain block letters. Pain squeezed her chest. Jeanette had seldom ordered anything, but when she did, she had been like a child at Christmas, eagerly awaiting the mail or a delivery service, beaming when the expected package finally arrived.

Karen carried the box into the kitchen and used a knife to slit the sealing tape. She opened the flaps and looked inside. There were some papers and a small book bound together with rubber bands, and on top lay a folded sheet of paper. She took the letter out of the box and unfolded it, glancing automatically at the bottom to see who had sent it. The scrawled name, "Dex," made her drop the letter, unread, back into the box.

Dear old Dad. Jeanette hadn't heard from him in at least four years. Karen hadn't actually spoken to him since she was thirteen and he had called to wish her a happy birthday. He had been drunk, it hadn't even been close to her birthday, and Jeanette had cried softly all night long after talking to her husband. That was the day all Karen's resentment and confusion and bitterness had congealed into hatred, and if she was at home the few times he had called after that, she had refused to speak to him. Jeanette had been distressed, but Karen figured that on the scale of things holding a grudge weighed a lot less than abandoning your wife and daughter, so she hadn't relented.

Leaving the box on the table, she trudged into the bedroom and peeled off her clothes, dropping the crumpled green uniform on the floor. Her feet ached, her head ached, her heart ached. The overtime she was working, in at six a.m. and off at six p.m., kept her mind occupied but added to her depression. She felt as if she hadn't seen sunlight in weeks.