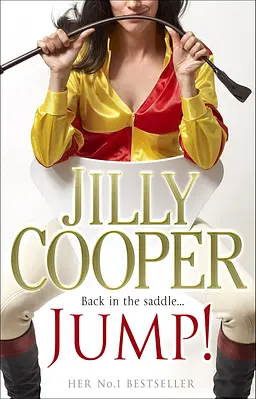

by Jilly Cooper

‘With luck she’ll be up and running soon after Christmas,’ said Charlie.

‘Well done, Etta and Tommy,’ added Marius with rare warmth.

Tommy needed every encouragement. With the departure of Michelle, Marius had made Josh rather than her head lad because he felt Josh would be better at keeping order than the gentle Tommy, though he was desperate to hold on to her because she was so good with the horses. Josh had consequently moved into the head lad’s cottage that Collie and his family had left. This had been redecorated, recarpeted and fitted with a new shower and kitchen, which delighted blonde Tresa, who had officially moved in with Josh.

The fact that Marius could afford to do up the cottage and buy back Furious convinced observers that he was receiving financial help from Valent.

Back at Throstledown, also in September, Marius held a parade of the horses to attract new owners and to enable existing ones to meet each other over an excellent lunch. Furious the unpredictable was shut away in a far-off field. To distract people from the hairiness of some of the horses’ ankles, the prettiest stable lasses, Tresa and Angel, were deputed to lead them past. The yard, however, looked wonderful, newly painted by Joey’s men, the buildings in good order, Etta’s flowers blooming in tubs and beds. There was definitely a feeling of renewal and optimism.

Unfortunately, Harvey-Holden had a parade on the same day with a band and a marquee, which took away a chunk of the clientele, and so did Rupert Campbell-Black. Rupert’s invitation said his yard needed advance warning of any helicopters landing. Lester Bolton would have given anything for such an invitation and would have used it as an excuse to buy a helicopter. He was irked that at Marius’s open day, no one bothered to introduce him to Lady Crowe or to Brigadier Parsons, who owned History Painting. He felt he and his princess had been slighted again.

He was also outraged that the moment he sold Furious back to Marius, the horse should win so spectacularly in that selling race at Stratford. He was not, however, as outraged as Carrie Bancroft, when she returned from Russia and discovered Trixie had ploughed all her exams.

‘You’ve been sacked from seven schools. You promised to work at this one. How could this have happened?’ yelled Carrie.

‘I didn’t work hard enough,’ admitted Trixie. ‘My hopes were slightly too high, I guess. For some beyond-me reason I failed.’

Carrie was even angrier when someone, probably Dora, leaked the story of the straight ‘U’ grades achieved by the daughter of the Businesswoman of the Year – did high achievers fail their children?

The atmosphere was truly dreadful, particularly when Uncle Martin, who had the hots for Trixie anyway, dropped in at Russet House and suggested that if his sister had been more caring and less of an absentee mother, and Alan not so obsessed with his writing, things would have been different. ‘Children need nourishing and encouraging. Frankly you neglect Trixie, Carrie.’

‘She does,’ agreed Trixie.

Martin indicated he’d be only too happy to be a father figure to his niece.

Meeting Tilda for lunch to discuss depression, Alan turned out to be the depressed one. He cheered up when Tilda said she’d be only too happy to give Trixie some coaching.

Etta, meanwhile, had expressed her worries about Trixie to Seth. ‘She’s so moody and unhappy, I’m sure it’s Josh officially moving in with Tresa.’

‘“Partners are all we need of hell,”’ smirked Seth and said he’d be only too happy to coach Trixie and act as a father figure in return for all Etta’s kindness in looking after Priceless.

‘He’s no trouble,’ lied Etta. When Seth smiled at her she could deny him nothing.

*

If Etta hadn’t had a brilliant win, when she did actually manage to get her money on Penscombe Poodle at Haydock, she would never have been brave enough to give a party to celebrate the end of Mrs Wilkinson’s box rest. She chose the second Sunday in September because Romy and Martin were taking their children to Wales for the weekend, which meant they wouldn’t be around to demoralize her, nor would their vast Range Rover be monopolizing the carport.

As well as all the syndicate, she asked Chris and Chrissie, Niall, Rogue, Amber and Marius and all the lads and lasses from the yard. She was amazed when so many accepted and particularly touched to receive a telephone call from Valent in China saying he hoped to be able to make it, and how great that Wilkie was better. Marius rang to say he’d be at Uttoxeter, alas, but his staff were really looking forward to it.

Etta decided to make a huge chilli con carne, accompanied by salads, and she picked enough blackberries and cookers, rejected by Mrs Wilkinson, who only liked sweet apples, to make two vast crumbles. Neither Seth, Corinna, Bonny, Lester nor Cindy had replied, which made catering difficult.

‘We’ll all bring things,’ said Painswick soothingly.

Shopping beforehand, Etta discovered that Ione Travis-Lock, who’d just been appointed a Master Composter, had set up her stall outside Waitrose and was bellowing at shoppers to make compost, avoid packaged food and buy fruit and veg from local suppliers. Etta scuttled inside. She had just bought mince for the chilli when she heard more yelling. Edging down the pet food aisle, she discovered Corinna about to detonate:

‘I’m afraid we only allow baskets with five items at this till,’ an unfortunate check-out assistant was telling her.

‘Do you know who I am?’ shouted Corinna. ‘I’m not going to wait in that queue. I have an interview with the Guardian in half an hour.’

‘I can’t help it, madam.’

Etta cringed beside the ramparts of Whiskas as Corinna started chucking items out of her basket. Curious customers retreated or ducked as tins of pâté, ripe Bries, jumbo prawns and a pineapple came flying past, until only four bottles of champagne and a packet of cigarettes were left.

‘Now will you let me through? I am one of the greatest classical actresses of my age, and you treat me like a chorus girl.’

‘Chekhov rather than Checkout,’ grinned Alan, when Etta told him later.

‘I do hope she’s in a better mood tomorrow,’ sighed Etta, who was making French dressing.

Chris had lent her two trestle tables from the pub, which he put up in the centre of the carport. These she would cover with the only two white damask tablecloths left from Bluebell Hill and use for glasses, silver, plates and food. Chris had only been able to spare a couple of dozen chairs, but the rest of the guests could perch on the little wall Joey had built round the garden she had made under the mature conifers. This was now filled with white flowers – Michaelmas daisies, dahlias, delphiniums, Iceberg roses and lilies – and looked, even Etta admitted, rather ravishing.

It would be a terrible squeeze, but people could always spill out into the road. Painswick, Tommy and Dora had all promised to help, and had already bathed Mrs Wilkinson and Chisolm.

For once Etta felt well organized and was determined to get an early night and try to look pretty, just in case Seth or Valent turned up. Alas, a sobbing Trixie rolled up at midnight. She’d had a dreadful row with her mother, could she sleep on Etta’s sofa? It was already occupied by Priceless, who took himself off to Etta’s bed.

At two, a terrible thunderstorm broke out. Priceless was terrified. Tranquillized, he passed out on even more of Etta’s bed, denying her any sleep as she tossed and turned, wondering if she had enough drink or whether Seth would get away from rehearsals.

81

At least a glorious day rose out of the first mists of autumn, meaning jump racing would soon be taking centre stage. Wandering out, the dew caressing her bare feet, breathing in a smell of mouldering leaves, Etta heard a rumble and a bleat and found Mrs Wilkinson and Chisolm demanding breakfast. Mrs Wilkinson had celebrated her new freedom by rolling extensively, covering herself with green muck.

‘Oh Wilkie, you’ll need another bath,’ wailed Etta.

After that, the morning ran away with itself. A huge saucepan of chilli was bubbling on the hob, salads were in the fr

idge, dressings mixed, glasses and silver sparkling. Etta had put on a frilly pale pink shirt and pink-striped trousers from the Blue Cross shop and just made up one eye, when she heard imperious tooting. Looking out she was horrified to see Martin, Romy, the children and the bloody Range Rover at the gate. So she rushed out to open it and Martin drove right in within an inch of the trestle tables.

‘You’re going to have to move those against the wall, Mother.’

‘But there won’t be enough room for people to sit. Can’t you park outside?’

‘And block all your guests? We knew you wouldn’t cope on your own, Mother, so we’ve specially cut short our weekend to support you,’ said Martin.

‘New outfit,’ said Romy accusingly, ‘we are splashing out.’

‘Granny looks cool,’ drawled Trixie, wandering out in the briefest of T-shirts. ‘What can I do?’

‘Get dressed, young lady,’ said Martin, ‘and clear up your mess in Mother’s living room and put back those cushions.’

‘Helloo!’ It was Painswick bearing a couple of quiches and two bottles of Chablis, and a huge bunch of carrots like an orange porcupine for Mrs Wilkinson, who practically broke the gate down.

Next moment, Priceless emerged from Etta’s bed with the munchies, gobbled up Gwenny’s breakfast, eyed Painswick’s quiches, then trotted purposefully out into the garden with one cushion that Trixie had just put back on the sofa after another.

Next to arrive were Joey and Woody, clutching six-packs. Sizing up the crises, they started opening bottles.

‘Now we’ve got some chaps,’ said Martin and was soon bossing them around to move the tables against the garden wall.

Etta’s right eye never did get made up. Glancing out of the kitchen window, she was so enchanted to see Valent’s red and grey helicopter landing on the helipad, and Mrs Wilkinson and Chisolm leaving their admirers beside the fence and rushing whickering and bleating up the hill to welcome him, that she absent-mindedly added a huge pinch of chilli powder.

‘Nothing much wrong with that horse,’ said the Major, who’d just arrived with Debbie.

Romy, not believing her mother-in-law was an adventurous enough cook, surreptitiously added another hefty pinch of chilli as Etta ran out of the house to greet Valent. As he walked down to the little orchard gate next to the mature conifer hedge, Wilkie and Chisolm trotted after him.

He was very suntanned and, although he looked more tired and thinner, he seemed much happier. He was wearing a pale blue shirt tucked into jeans and he bent and kissed her on the cheek.

‘Wilkie’s sound.’ He scratched Mrs Wilkinson’s neck as she frisked his pockets. ‘You wrought another miracle.’

Then he looked round at the crowds piling into what was left of Etta’s tiny garden after the aggressive parking of Martin’s car and, unlocking the gate, invited everyone to spread out into the orchard, where the apples were reddening or turning gold.

‘Yuck, there’s poo in the field,’ said Drummond loudly.

‘Takes one to know one, you little shit,’ murmured Joey.

‘Mrs Wilkinson is the guest of honour,’ said Valent. ‘She needs to mingle with her friends.’

Chisolm was already showing off, clambering up trees from which she’d stripped the bark in search of pears to drop down on guests.

Hoping Dora and Trixie would soon turn up to push bottles round, Etta charged about seeing people at least had a first drink. Valent, grabbing a can of beer, had headed straight for the Throstledown stable lads, singling out Rafiq.

‘Well done, lad, you certainly sorted out Furious. When’s he running again?’

‘Marius hasn’t said, he prefers soft going.’

‘Well, he must put you up again, bluddy good.’

Valent then said he’d been spending a lot of time in Pakistan, and asked where Rafiq’s family lived.

Valent’s really, really taking trouble, thought Tommy gratefully, exactly what Rafiq needs.

Carrie and Alan, who’d spent much of the night rowing over Trixie, were the next to arrive.

‘Mother, you’ve been at the bottle,’ accused Carrie, examining Etta’s gold hair.

‘And you look gorgeous,’ said Alan.

‘Not sure at your age,’ persisted Carrie.

‘And your hair looks as though you’ve been pulled through a hedge fund backwards,’ Trixie told her mother, as she finally emerged from Etta’s bedroom, ravishing in the shortest of strapless blue and white flower-printed dresses, reeking of her 24 Faubourg.

A wolf whistle greeted her. Turning, she saw Seth in the doorway, ostentatiously staggering in under a crate of red.

‘That’s far too much,’ gasped Etta. ‘You are kind, you got away from rehearsals in time!’ She was so amazed and thrilled to see him, she added another pinch of chilli.

‘I’ve just been hearing about my Millennium Cup,’ said Valent, also appearing in the doorway. ‘Didn’t know you’d been tending my roses as well,’ he chuckled. ‘Gives me a buzz to beat Ione and Debbie, and your garden looks smashing. Here, let me carry that,’ he said, taking the vast saucepan of chilli and putting it on the table outside. ‘I’m famished, didn’t have time for breakfast.’

‘Oh, please help yourself,’ Etta handed him a plate. ‘Let me get you another beer. I’m so thrilled you came.’

The result, alas, was a chilli hotter than hell. Caring Romy rushed back to the barn and returned with a big chicken pie she’d bought last week from Waitrose and defrosted in the microwave. She took the opportunity to change into a ravishing strapless white dress, which showed a lot of leg and cleavage.

‘I was too hot before.’

‘Like the chilli,’ said Seth.

Most of the syndicate had fortunately brought quiches and pies.

But Valent valiantly, among others, ploughed his way through the chilli, his eyes watering, his face growing redder and redder.

‘It’s quite inedible, Mother,’ said Carrie, picking at a slice of Painswick’s quiche. ‘If you had fewer guests, I’d whisk them off to a restaurant.’

A mortified Etta rushed round, apologizing frantically and offering people glasses of water. She was then amazed to discover that Joey had dumped a crate of champagne brought by Valent in the kitchen. People were soon knocking this back to cool themselves down.

Much of the rejected chilli ended up in the long grass along the north side of Valent’s conifer hedge, where it was finished up by Chisolm, Cadbury and Priceless until real tears poured out of their eyes. Mrs Wilkinson was in heaven, however, bustling about chatting to all her friends, resting her head on their shoulders, shaking hooves, peeling bananas to order, sipping champagne. Chisolm, already pissed, was butting people in the backside.

‘Where’s Tilda?’ asked Painswick.

‘Coming,’ said Pocock. ‘She’s got a lot of lessons to prepare.’

Inadvertently, Tilda had recently upset both Romy and Carrie, telling the former that Drummond was developing into a bit of a bully, and his language should be watched.

‘Doesn’t get that from our house,’ Romy had snapped. ‘Must be listening to my mother-in-law’s builder friends.’

Tilda had been coaching Trixie, and told Alan that the child was desperate for her mother’s approval. ‘She’s really clever, she just needs a reason to succeed, some interest in her future, not just rants when she fails.’

Alan, in a row last night, had been unwise enough to pass this on to Carrie.

‘Doesn’t Wilkie look well,’ said Valent, as she nudgingly followed him round.

‘I think the feng shui in the office really worked on her,’ Etta couldn’t resist saying.

Valent grinned. ‘Bonny says I have an excess of Yang.’

‘They try to tell us we’re too yang,’ said Etta. ‘Do you remember? Sung by Jimmy Young, or Yang?’ she giggled. ‘How is Bonny? I’m so sorry about the chilli.’

‘It was fine, it’s a lovely party.’

Looking round his field he cou

ld see Niall, back from Matins, sitting on the grass with Woody and talking to Joey and Chrissie. Chris was opening bottles and buttling.

Valent next questioned Painswick about the yard. ‘Marius has gone to Uttoxeter,’ she said. ‘He works so hard, but he’s so thrilled about Furious.’

So was Valent, who’d secretly bought him.

Direct Debbie even congratulated Etta on her garden.

‘To grow those plants with so little sun is impressive. I’ll give you my scarlet kniphofia Percy’s Pride to brighten things up a bit.’

Rafiq, still dazed from having such a long and encouraging conversation with Valent, lay on his back looking up at lemonyellow flowers of traveller’s joy. Josh, handsome, tanned and just back from a week in Portugal, didn’t know how to handle Trixie, who he had to admit was looking well fit. Lester was bending the Major’s ear.

‘I want Mrs Wilkinson in my Godiva film. If she can canter around the orchard, she can carry Cindy for a week or so.’

Seth was talking to Trixie.

‘Valent is too old for jeans,’ he was saying dismissively, ‘particularly with those great muscular footballer’s thighs.’

‘He looks pretty cool for a coffin-dodger,’ said Trixie, who was looking at Josh and deciding she was still mad about him.

82

Etta poured drink after drink, continuing to apologize for the chilli. At least everyone loved her crumbles and the salads had gone down well.

She felt suddenly deflated when Valent came up and said he had to go.

‘I’ve got to be in Shanghai for a meeting first thing.’

‘You came all the way for Wilkie’s party?’

‘More or less. Bonny’s in London doing a television programme. I’ll be back later in the autumn and we’ll get Wilkie up and running. How’s Alan getting on with her biography?’