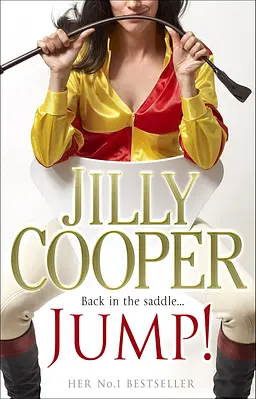

by Jilly Cooper

Bonny’s acceptance speech was long and tearful, thanking her ‘significant other, Valent Edwards’, who was blushing and squirming with pride and embarrassment in the stalls.

‘Beetrooted to the spot,’ said Seth scornfully. ‘Talk about Bonny and Clod.’

‘Valent looks sweet,’ protested Etta.

Bonny was wearing a short strapless pale grey silk sheath dress which seemed to merge into her luminously pearly shoulders, touchingly slender neck and long fawn’s legs. She had the huge-eyed, hauntingly sad face of the Little Mermaid. Life would be spent treading on knives.

At that moment, Corinna’s mobile rang. It was Phoebe.

‘Quick, quick, Miss Waters, so exciting, Bonny’s on television, she’s won a BAFTA.’

‘We know,’ said Corinna and hung up.

‘Just look at her gorgeous diamonds,’ murmured Alan. ‘Twinkle, twinkle, little star.’

‘Valent must have emptied Asprey,’ grumbled Corinna.

Bonny was now paying tribute to everyone who’d helped her on her life’s journey.

‘Why doesn’t she mention Mr Whiskers the gerbil and Gordon the goldfish?’ snorted Corinna. As she threw a cushion at the television, lots of feathers fell out. ‘I’ve always thought BAFTA stands for Bloody Awful Film and Television Actress.’

Seth laughed and topped up her and Etta’s glasses.

‘I wonder if she’ll make the races tomorrow,’ asked Etta. ‘After such celebrations, she’ll have a hangover.’

‘She doesn’t drink,’ said Alan.

‘That’s a hammer blow,’ said Seth. ‘Christ, you can see why Valent’s besotted.’

The Major was also turned on. Debbie, who had wanted to look as nice as possible tomorrow, was irked when her beauty sleep was disturbed again by the Major’s cock nudging her coccyx.

‘Wakey, wakey,’ murmured the Major, ‘here comes Snakey.’

Debbie sighed and rolled over.

Before she and Phoebe even met Bonny, they had decided to hero-worship her, knowing how much this would enrage Corinna.

The telephone was ringing as Etta got home from watching the BAFTAs. It was Valent to say he had a meeting in North Yorkshire tomorrow so he and Bonny would be joining the syndicate at Wetherby.

‘I’m sending you a DVD of her new film, The Blossoming.’

‘I’ll watch it then we’ll have something to talk about,’ said Etta, not sure how au fait she was with abuse and rape.

‘Bonny comes across as super-confident but underneath she’s shy, talks a lot of highfalutin stoof.’

‘She’s very young,’ said Etta, then, regretting it: ‘She adores you, lovely the way she singled you out this evening.’

Then she told Valent about Furious making his debut at Wetherby with Rogue. ‘I wish Rafiq was riding him, he’s the only one who can get a tune out of Furious. If only Marius’d send him on a jockey’s course, then he could get a licence. He feels he’s not going anywhere and he’s so worried about Pakistan. He’s such a sweet boy.’

‘Wilkie’ll be getting jealous,’ said Valent. ‘Don’t forget the orchard’s booked for her and Chisolm in the summer. And thunks so much for the bulbs, Etta, the garden looks smashing and thunk you for writing to Bonny and for the birthday card, so nice of you to remember. See you at Wetherby.’

Etta always felt so much happier when she’d been talking to Valent.

64

There are great problems for trainers in having horses owned by a syndicate. You never know when and if a horse is going to run. People take a day’s holiday from work, fly down from somewhere, charter a plane or a box, then horses get colic or pull muscles on the gallops. It’s desperately difficult to get it right.

Racing is also ruled by the weather. A scorching day of sun or thirty-six hours of deluge or a sharp frost can put a horse out of a race. But it’s a brave trainer who pulls a horse if the entire syndicate is descending from all over the country to watch it and is booked into hotels, having cancelled board meetings, sports days, major speeches, and arranged later liaisons with mistresses, only to discover their horse has been withdrawn. Owners, in addition, are often rich men and women used to calling the shots.

Unlike Harvey-Holden, who overran his horses to appease his owners, Marius frequently drove horses miles to races then refused to run them unless the going suited them perfectly, particularly if a horse had been off as long as Sir Cuthbert or was a beginner like Mrs Wilkinson or Furious. Painswick’s new job involved a lot of time emailing apologies or fielding expletives.

Due to leave at nine, the Willowwood syndicate set off very late for Wetherby. Stefan the Pole, making Corinna up and attempting to repair last night’s ravages, had great difficulty applying lipstick because she kept yelling at Seth. A new short citrus-yellow coat, worn with a big black Stetson, needed different make-up. Tempers were not improved by four hours in a hot bus.

The traffic was frightful. Marius’s horses had a nightmare six-hour journey through gales and torrential rain. Mrs Wilkinson arrived in a terrible state, sweating up despite the cold and badly gashed in the shoulder where Furious had bitten her. She was missing Chisolm and Tommy, and Rafiq, the other lad she particularly loved, was preoccupied with Furious.

Deluge followed by brilliant sunshine had dried out the course, a fast-galloping clay track which could get waterlogged in places. Mrs Wilkinson hated soft ground. Marius was tearing his dark brown hair out. It was Bonny Richards’s first visit to the races and, as Painswick assured him, most of the syndicate had bought new outfits.

Amber, who took her all-too-few rides seriously, had arrived early and spent a long time walking the course, measuring strides, looking for boggy ground and angles that might cause trouble.

She had also dragged along her father Billy, ex-Olympic showjumper, television superstar. Although he was adored by the public, Billy’s job was under threat. Having drunk too much over the years, he was given to fluffing lines and speaking his mind on air. He had expressed horror at possible relocation to Manchester and was also considered ‘too posh’, which didn’t go down well in the penny-pinching, puritan, egalitarian mood at Television Centre. All equine sports were being pruned and plenty of young turks were after Billy’s job. His tousled light brown curls were touched with grey, but the enchanting smile and the air of life being a little too much (which it was now) hadn’t changed.

Having escaped from the BBC for the day, he was extremely helpful at pointing out hazards.

‘Go steady or you won’t get round. Ground’s bottomless and very wet, tell Mrs Wilkinson to bring her bikini. Don’t go for gaps in hurdles, she’s got a short stride, might catch her little feet. Very proud, darling, if you win today it’s three out of three.’

‘Thanks, Dad. Marius is such a shit, he never encourages me or gives me advice. It’s just “Why’d you do that?”, “Why didn’t you do this?”’

‘Rupert was like that when we were showjumping,’ said Billy. ‘Christ, I need a drink.’

A bitter east wind tugged at the last lank curls of old man’s beard hanging from the bare trees. It was only eleven in the morning and Billy had smoked all the way round. Amber was horrified how grey he looked in the open air.

‘You OK, Dad? Mum playing you up?’

‘No, no,’ lied Billy.

‘Rogue’s asked me out this evening,’ she couldn’t resist telling him.

‘Don’t get hurt, darling. He’s charming, but an even worse womanizer than Rupert used to be.’

‘I can look after myself. Don’t tell Mum, she’s bound to tell the press if Dora doesn’t get there first.’

Amber had been so busy, rising early, driving up and walking the course, she hadn’t looked at the papers. On her return to the stables, Michelle with a smug smile handed her the Evening Standard, which had been brought up by a southern owner.

‘Rogue’s been a naughty boy again.’

On an inside page was a picture of a plastered Rogue with his arm round an

equally plastered, very pretty actress called Tara Wilson, as they emerged from a nightclub at one o’clock in the morning.

‘He’s always had the hots for Tara,’ smirked Michelle.

Determined not to show how outraged and desperately hurt she was, Amber stumbled off to see Wilkie and ran slap into Marius, who, sheltering his mobile from the downpour, was shouting out his code number and declaring Mrs Wilkinson a non-runner in the 3.15.

Then, as Amber gave a wail of horror, he turned on her.

‘She’s boiled over, sweated up and used all her energy. I’m not risking her on this ground, she’s not right.’

And Amber lost it. She wouldn’t get paid now and she’d spent a fortune on petrol, getting herself waxed and on a clinging catkin-yellow jersey dress to ensnare Rogue … Fucking Rogue, fucking Marius.

‘It’s pathetic not to run her when she’s come all this way. I’ve just spent hours walking the course, I know where the danger spots are.’

‘This going’ll put six inches on the fences. Unlike Harvey-Holden, I don’t run unfit horses to appease owners,’ growled Marius.

‘At least he gets results,’ screamed Amber. ‘It’s only a drop of rain.’

At that moment, God turned the tap on, drenching them both. Hearing shouting, Etta ran out of Wilkie’s box in alarm.

‘Marius isn’t going to run Wilkie,’ stormed Amber.

Etta’s first emotion was profound relief, followed by alarm for Amber, who, as grinning staff from other yards braved the down-pour to eavesdrop, would certainly never get another ride from Marius if she didn’t shut up.

The syndicate had arrived half an hour ago and immediately repaired to the famous White Rose restaurant in the stands for large drinks and an early lunch. Etta, however, had sloped off to the stables to find a distraught Mrs Wilkinson, reminiscent of her terror in the early days. To compound the image, here was Valent, splashing through the puddles, looming more menacingly than the huge black clouds overhead. He’d go berserk, having brought Bonny up here, if Wilkie didn’t run.

Knowing Marius needed a bottle of whisky before telling an owner his horse had broken down, Etta waded in.

‘I’m desperately sorry, Mrs Wilkinson’s not going to run. She’s a little horse and this kind of going puts six inches on the fences,’ she stammered, wiping rain which Valent thought was tears off her face. ‘And the light’s awful and Wilkie’s only got one eye, and the mud can kick up into her face, and she didn’t travel well. I’m so sorry you’ve come all this way.’

Valent had just left Bonny in the warmth of the White Rose. Already that morning, he had made a detour in the North Riding with the intention of introducing Bonny over breakfast to his son Ryan, the football manager. Bonny, who was very much aware of and resented Valent’s children’s disapproval, had needed a lot of coaxing. She had spent a great deal more than Amber on a demure little dove-grey dress, so as not to appear a wicked step-mother. She had also seen photographs of the handsome Ryan and, assuming instant conquest, was furious on arrival at the club to find he had flown off to Spain to look at a new striker.

Ryan loved his father and would have liked to discuss the possible new signing with him but, watching the BAFTAs, he had been dazzled less by Bonny than by the £50,000 worth of diamonds round her slender neck, which she later told the press was a present from Valent. Disliking Valent squandering his in-heritance, Ryan had pushed off to the airport.

Bonny had never been so insulted. Valent, shy and ill at ease among luvvies, had drunk heavily at the BAFTAs. Bonny had not. In the argument that followed about the appalling way he and Pauline had reared their children, Bonny’s screams had pierced his hangover like needles dipped in acid …

He had felt humiliated and was livid with Bonny for slagging off Pauline. The last straw was Bonny yelling: ‘And it’s a hangover, not an ’angover, Valent.’

He was about to take it out on Etta, when Mrs Wilkinson’s head appeared over the half-door and with infinite tact, she whickered despairingly.

Gratified, Valent moved forward, his angry red face suddenly softening. He pulled her ears, scratched her neck, raked her mane with his huge hands.

‘Poor little luv, had a bad journey, did you? Makes two of us.’

Then he turned to an equally apprehensive Amber, Marius and Etta.

‘These things happen, right decision. It’s so dark today, wouldn’t be easy for her to see with two eyes, would it, little girl?’

Mrs Wilkinson nudged him in the ribs in agreement.

‘I feel so awful it’s Bonny’s first race,’ stammered Etta. ‘Such a long way.’

‘Doesn’t matter, we want her to run again.’ He smiled at Amber. ‘Sorry, luv, disappointing for you, but something will come up soon. Let’s go and have a drink, we’ll leave Bonny to settle.’

Oh, you dear, dear man, thought Etta, as he led them into the nearest bar.

65

It was like a game of consequences. Bonny Richards met Corinna Waters, who’d already downed a pint of champagne at the White Rose restaurant overlooking the entrance to the racecourse.

Bonny, having positioned herself so the light fell on her flawless, unlined face, said to Corinna, ‘You are an icon, Miss Waters. You have been my favourite actress ever since my father took me to see you playing Hester in The Deep Blue Sea when I was a very little girl and I was hooked. I vowed that one day I would portray the suffering of older women. Whenever I seek inspiration I revisit your oeuvre.’

‘Charmed, I’m sure.’ Corinna took a slug of champagne. ‘But I was actually the youngest Hester ever seen in the West End.’

Bonny, however, was not to be deflected.

‘My other icon is Sarah Bernhardt.’ Then, to show she’d done her homework: ‘Like you, Miss Waters, Sarah triumphed as Phèdre.’

‘Both legless,’ drawled Seth.

‘Bastard,’ hissed Corinna.

‘Hi, Bonny, I’m Seth Bainton.’

Good-looking, unprincipled, terrifyingly charming, Seth smiled down at Bonny, and she made a smooth transition from heroine to hero-worship.

‘Indeed I know,’ Bonny gazed up admiringly. ‘Corinna’ (she pronounced it Coroner) ‘must be so proud of your versatility, as at home in Hamlet as in Holby City. With each part, you take us on a journey, truly connecting us with your character.’

Seth was actually blushing.

‘Christ, she’s awful,’ Alan muttered to Joey, then blushed himself when Bonny told him how much she admired his oeuvre and how much she was looking forward to his seminal work on depression.

‘A subject on which I should like to exchange views. I feel I could have input.’

‘I’m sure you could. What a darling,’ Alan murmured to Seth.

‘And you must be Etta.’ Bonny seized Debbie’s hands and was shaking them up and down. ‘Valent has described you so often, I feel we are old friends.’

‘That’s not Etta, Etta’s beautiful,’ muttered Seth, whose diction was a bit too good and who received a scowl from Debbie.

‘This is Debbie Cunliffe, who’s lovely in a different way,’ said Alan hastily. ‘Etta’s gone to the stables to check on her precious Wilkie.’ Then, seeing Bonny’s eyes narrow: ‘She’ll be along in a tick.’

‘And you must be Debbie’s spouse, who makes everything run like clockwork.’ Bonny gave a bemused and ecstatic Major a little kiss.

‘And you must be Shagger, I can see why you’ve earned your naughty nickname. And I know Alban. How are you, Alban? Valent has so enjoyed engaging with you.’

‘Fritefly kind, very good of him.’

Corinna, after a late night and four hours on a bus, was edging towards a table in the dark of the restaurant. Bonny, trailing admirers, headed for one near the big floor-to-ceiling window overlooking flower beds and the entrance to the course, and where the harsh north light fell lovingly on her wild-rose complexion.

Everyone in the restaurant was nudging and craning. Older men, mostly members of the

Check Republic, straightened their silk ties, whipping on their spectacles to look then whipping them off to seem more attractive, seeking identification from their wives. ‘Who’s she, who is she?’

Many recognized Corinna and some of them Seth. He slid in next to Bonny, who pointed to the seat opposite which was equally exposed to the harsh light, crying, ‘I want my icon to sit there.’

Fractionally mollified, Corinna sat down.

‘What are you reading?’ asked Bonny.

Corinna waved Macbeth, which after the earlier tour in America was being given a short West End run. ‘I immerse myself in every part, even relearning lines is tough in so short a time.’

‘I don’t have a problem with lines,’ Bonny opened her big eyes even wider, ‘but I guess I’m that much younger.’

‘Your generation don’t bother to absorb the meaning,’ said Corinna rudely. ‘Valent sent us a tape of The Blossoming, couldn’t make head nor tail what it was about. None of you enunciate these days.’

‘You’re probably used to an older theatre audience,’ said Bonny sweetly, ‘some of them not wearing hearing aids, so you’ve got to shout.’

‘My generation combined clarity with subtlety,’ snapped Corinna.

‘I found The Blossoming very moving,’ said Debbie, who had maddeningly plonked herself next to Corinna to be near Bonny, on whose left a grinning Alan had seated himself.

‘Do you see Valent as the older man in The Blossoming?’ he asked.

‘There are elements in the movie which are reflective of the politics of our relationship,’ Bonny nodded sagely. ‘Valent is a guy, intelligent, kind, compassionate’ – where the hell was he? – ‘and strong enough to stand up to me.’

‘Could have fooled me,’ muttered Joey, who was still marking the Racing Post. ‘We better order some grub or we’ll miss the first race.’

Joey was not really enjoying himself. He knew from Bonny’s frosty looks she didn’t approve of him skiving and being part of the syndicate. He missed Chrissie and his mate Woody. This lot were a bit posh. He was also very worried about Woody, who was getting himself snarled up trying to save the Willowwood Chestnut, the beautiful tree in Lester Bolton’s garden that had provided conkers for generations of Willowwood children.