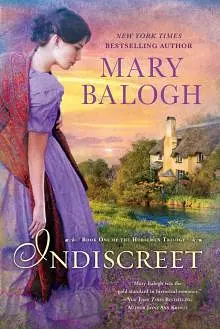

by Mary Balogh

She had not refused Rex—perhaps because this time she had realized what was ahead. She had lost her courage to do what she wanted to do regardless of the consequences.

He had just called her a coward. Because she did not want to go back to London. But she did not need the wisdom of advancing age to know what would be ahead of her there. Did he realize? He had spent so many of his adult years with England’s armies overseas. Did he realize?

She could not go. She closed her eyes and lowered her forehead to the balustrade. She could not.

But choices had been taken away from her—again. All choices. She had married him three weeks ago. She had promised to obey him. He had just said they were going to London. She had no choice.

Ah, dear God, they were going to London.

• • •

HE was not at all sure that he was doing the right thing. He knew that he was quite possibly exposing his wife to a humiliation and a degradation from which she might never recover. And he knew quite well that he might be destroying his marriage. It was possible, even probable, that she would never stop hating him after this.

But he was sure of one thing. He was sure that he was doing the only possible thing. She was his wife. She would run and hide again now if he would allow it. But he would not allow it. Not ever. And there would be no cowering at home either. Sooner or later the truth would catch up to them there. And even if it did not, he would not allow her to be trapped there for a lifetime. Eventually there would be children to take out into the world, children who would have to deal with their mother’s past.

He would prefer to deal with it himself.

He looked from the carriage windows at the distinctive sights of the outskirts of London. They would be at Rawleigh House soon—he had sent word ahead to have it opened and prepared. There was no going back now.

She sat beside him, as she had sat all the way from Kent, like a marble statue. They had not exchanged a dozen words. He wanted to offer her some comfort. But he had found himself quite incapable of doing so since the night before last. How did one comfort a woman who had been living quietly and respectably and usefully just a few weeks ago when one had brought her to this? And the comparisons had been quite obvious to him even before she had made them more so on the bridge yesterday afternoon.

Ken and Eden and Nat had tried to persuade him yesterday morning that they really had intended to stay just for a day en route to London. They had been very loud and jolly about it. It had felt as if there were a solid brick wall ten feet high between him and them. It was safe to go to town after all, Eden had said. His married lady and her husband had departed for their home in the North, and Nat figured that his single young lady—or rather her large family—must have got the message from his lengthy absence. It would be safe to go back. They had all tried to chatter together, the three of them.

“It is really quite all right, you know,” the viscount had said finally and quite firmly, putting an abrupt end to both the chatter and the forced high spirits. “I have known Catherine’s story since before our marriage. Did you believe I did not? How could I have married her if I had not known? The name on the license and register would have been false. The marriage would have been invalid. I was merely taken aback yesterday to discover that Ken knew it. I have been foolishly trying to protect her by keeping her quietly here.”

The looks on their faces had assured him that since the morning before, Eden and Nat had been told the story. Ken would have known it was safe to do so. The story would go no further through them.

“He is easily England’s most despicable blackguard, you know, Rex,” Ken had said. “You know that from your past experience. I never did believe Lady Catherine entirely or even mainly to blame. Many people felt as I did.”

“You do not have to defend her to me,” the viscount had said. “She is my wife and I love her. And she was not even partly to blame. She was ravished.”

“Yet he would not marry her?” Nat had sounded appalled. “Why did Paxton not kill him?”

“She would not marry him,” Lord Rawleigh had said.

“The devil!” Eden had said. “Even though—” He had cut himself off with a muffled oath.

“Even though she was with child,” the viscount had completed quietly. “She is a courageous woman, my Catherine. I need advice.”

Perhaps it was not quite the thing to ask advice of his friends for his marriage. But this was not a personal thing. And he would trust these three with his life—and had done so more times than he could count.

They had given advice, none of which he would have taken if it had contradicted what he had already known he must do. But they had all been agreed, all four of them. It had been quite unanimous.

He must take her back to London.

But his talk with his friends had revealed to him with appalling clarity the spreading and disastrous effects of his relentless pursuit of her at Bodley. He had brought fresh ruin on her because, like Copley, he had refused to take no for an answer. Oh, he had not raped her. He could console himself with that fact, perhaps. But he was not consoled nonetheless. She had chosen a way of life and she had been living it with cheerfulness and dignity. He had taken her from that and brought her to this.

How could he comfort her? He looked at her again across the carriage as they approached Mayfair and the more fashionable homes of the wealthy and titled. She was not even looking from the window. He had been unable to go to her either last night or the night before. He found himself unable to touch her except in purely impersonal ways, like assisting her in and out of his carriage. He found himself unable to talk to her.

He wondered if he would ever be able to forgive himself. He doubted it.

20

CATHERINE had been left much to her own devices for the four days since their arrival in town. She had seen little of her husband, either by day or by night. She did not question his long absences from home, though she knew those absences did not extend into the nights. He slept in his own room, the width of their two dressing rooms between them.

She was not with child. She had discovered that the day they left Stratton Park. Perhaps it was as well, she thought after the first twinge of disappointment. Although he had refused to send her away, he would surely agree to do so once he realized the disaster that would result from bringing her here. He had said he wanted children of her, but he would change his mind once he had realized the impossibility of a workable marriage with her. Finding herself with child now would only have complicated matters hopelessly. But there would be no further chance of its happening—he had stopped coming to her bed.

She did not go beyond the confines of the house and garden. She was sorry for Toby’s sake. The garden was not very large and she knew he would love nothing better than a good run. She would have taken him to Hyde Park, but one never knew whom one might run into there even in the early morning.

She was letting life happen to her again, as she had done during the week before her marriage. Her life was beyond her control anyway—it was in her husband’s hands. She did not try to fight him after that afternoon on the bridge when he had told her they were coming to London. She merely hoped that before she was forced to go out he would realize for himself that it was an impossible situation, that the only thing to do was to go back to Stratton.

But her hopes were dashed on the fifth day. He came back home late in the morning and found her in the morning room, seated at an escritoire writing a letter to Miss Downes.

“Here you are,” he said, striding across the room toward her. He looked down briefly at her letter, though he did not try to read it. “I have brought a visitor for you, Catherine. He is in the library. Come and meet him.”

“Who?” Her stomach lurched. “Another of your friends? I think not, Rex. You go along. I will stay here and finish my letter.”

“Come.” He set a hand on her shoulder. H

is voice was quiet, but she had learned something about her husband in a month of marriage—perhaps she had learned it even before then. He had a quite implacable will. He was not giving her a choice. “Toby, you stay here, sir, and guard the room against intruders.”

Toby wagged his tail and stayed.

Her husband had a hand at the small of her back when a footman opened the door to the library for them. She stepped inside.

He was a very young man, and he had obviously been pacing before their arrival. He stopped halfway between the desk and the window and turned toward the door—a golden-haired, hazel-eyed young man who must have a good-humored face when it was not filled with anxiety as it was now. It paled on sight of her.

She almost did not recognize him. He had been only twelve the last time she had seen him. He had been away at school during the Season.

“Cathy?” he whispered.

“Harry.” Her lips formed his name but no sound came. Oh, Harry. Such a very handsome, pleasing young man.

“Cathy?” He said her name again. “It really is you. I could scarce believe it even when Rawleigh insisted on it. I thought you were dead.” He turned paler, if that was possible.

“Harry.” Sound came out this time. “Oh, Harry, you are all grown-up.” She walked toward him without quite realizing what she did and reached out a hand to touch the lapel of his coat. “And tall.” Her eyes filled with sudden tears.

“You died in childbed at Aunt Phillips’s,” he said. “Or so Papa told me. But we did not wear mourning because . . .”

She smiled through her tears.

“Perhaps we should all sit down.” It was her husband’s voice, cool and very sane. “Come, Catherine, Perry. This is a shock for both of you.”

“Viscount Perry,” she said, setting her free hand against her brother’s other lapel. “The title sounds grander now that you are grown-up. Harry, can you—”

But she had seen the sudden tears in his eyes too. And then his arms were about her, holding her fiercely against him. “Cathy,” he said, “Rawleigh told me at White’s that none of what happened was your fault. I believe him. But even if it was . . . oh, even if it was.”

She had loved him and cared for him like a mother, even though she was only six years older than he. Their own mother had been sickly after his birth and had died before his third birthday. Catherine had poured all the love of her heart on her little brother and had spent all her free time with him. He in turn had worshiped her. She could remember his announcing when he was five years old that he was going to be an old bachelor when he grew up so that he could look after her forever and ever.

They sat down together on a sofa while her husband took a chair beside the fireplace. She held her brother’s hand. It was slender, like the rest of him, but there was manly strength in it. In a few years’ time, she thought with pride, he was going to set countless female hearts fluttering.

“Tell me about yourself.” She gazed at him, ravenous suddenly for news of the missing years. He had thought her dead. She had lived as if he were dead, never making any attempt to communicate with him or learn anything about him. It had been another of the conditions. But she did not believe she would have tried anyway. It had been too painful even to think of him. “Tell me everything.”

“Some other time,” her husband said firmly, though not ungently. “There are other things to be talked about for now, Catherine. I think you must agree, though, that something good has come of your returning to London.”

She was not so sure. Seeing Harry again, touching him, knowing that his long silence had not been caused by rejection, was all sweet agony. And he had said that he believed Rex, and that even if he had not, he would not condemn her. But he could not allow himself to be seen with her. He was a young man with his own way to make in Society. Even the taint of her memory might be a hindrance to him. Her return would be an impossibility.

“Rawleigh says you are going to call on Papa this afternoon,” Harry said. “I think it is a good idea, Cathy, now that you are married.”

“No,” she said sharply, turning her head to look at her husband. He was gazing steadily back at her, his expression harsh, his eyes narrowed. “No, Rex.”

“Everyone knows I have a wife,” he said. “Everyone is avidly curious. You have probably seen the pile of invitations that have been arriving yesterday and today. I have chosen Lady Mindell’s ball tomorrow evening for your first appearance. Eden and Nat and Ken will be there as well as your brother. And Daphne and Clayton too—I have been waiting for their arrival in town. They came last night. You will be surrounded by friends. And of course you will have me. The stage is set, one might say.”

She was too paralyzed with terror to reply. She was unaware of the fact that she was gripping her brother’s hand very tightly.

“But we do need to call on your father first,” her husband said. “It is only fair that he know of your return, Catherine, before everyone else does. Does he know you have left Bodley-on-the-Water? Have you written to him?”

She shook her head. He had probably sent her quarterly allowance there. She had not thought of it.

“I sent my card in this morning,” he said, “with notice of my intention to call this afternoon with my wife.”

No. The word formed on her lips, but she did not speak it. What was the point? He would take her whether she wished it or not, whether she begged or not. And he would take her to Lady Mindell’s ball. Harry’s Season might be ruined. It was the only really coherent thought that would form in her mind. She looked at him.

“I know you are terrified, Cathy,” he said. “But I believe Rawleigh is right. When I think of what you had to go through, and when I think that for five years you have been all alone because I was told you were dead . . . Well, when I think about it, it makes me just furious. I always have thought that the rules are not fair to women. They get the worst of everything even if they do not break the rules. Whereas men . . . He has been running loose here all this time, doing it again to other women, though I do not believe he has ever again done quite what he did to you.”

Her husband’s eyes, she saw when she glanced at him, were as hard as flint.

“Have courage, Cathy,” Harry said, raising their clasped hands to his lips and kissing the backs of hers. “You were always so courageous. When Papa told me that you had ensured your own permanent ruin by refusing to marry Copley, I was so very proud of you. I do not know any other woman who would have had the courage to thumb her nose at Society.”

She gazed at him for a few moments and then at her husband. Both looked silently back at her. There was a curious tension in the library, just as if she had a choice. Just as if they were waiting for her decision and would accept it whatever it was.

Her father had not fought for her. Whether he had believed her or not she did not know. But he had done nothing to defend her. He had only done everything in his power to force her into marriage with the man who had ravished her and impregnated her. When she had finally gone away, both from him and from her Aunt Phillips’s, he had told Harry she was dead. But he had refused to let Harry go into mourning for her because she had been a fallen woman.

Society had condemned her to perpetual exile. Because she had been ravished and had failed to marry her ravisher. He, on the other hand, had been free to continue in Society even if he was frowned upon by the highest sticklers as a rake. Society secretly loved rakes. They were seen as virile, high-spirited adventurers, and very masculine. He had done it again, Harry had just said. He had hurt, perhaps ruined, other ladies of the ton who, like her, had been naive enough to be attracted by his charm and his reputation.

No one had ever stopped him.

And now she was married to a man of the ton. It was a marriage that had begun in bitterness but had developed quickly and unexpectedly into something rather sweet and certainly valuable. The success, the very co

ntinued existence of her marriage, now hung in the balance. Because Society had rejected her. Because she had been ravished.

And she had accepted it all. Meekly. Sometimes abjectly. Recently she had been quite abject. She had begged and pleaded. She had allowed herself to be whipped into submission.

But she wanted to fight, she realized suddenly. She wanted to fight for Harry. Now that they had found each other again, she did not want to lose him. And she wanted to fight for Rex, for their marriage. It had never been perfection, but it had come curiously close during those two weeks at Stratton. It was worth fighting for. And he was worth fighting for. She could not bear the thought of losing him. She loved him—she stopped blocking the thought as she had been doing for the past week.

She loved him.

And she wanted to fight for herself. Perhaps most of all for herself. She had done nothing to be ashamed of—either with Sir Howard Copley or with Rex. She had done some foolish things, perhaps, some weak things, but nothing wrong enough to bring shame on her. She had been made a victim and recently at least she had behaved like a victim. She did not like the feeling and she did not like herself for cringing against it. And self-respect, when all was said and done, was a person’s most precious attribute. If one could not respect and like oneself, then all was lost.

There had been a lengthy silence. When she glanced at her husband eventually, she found that he was looking intently back at her, a gleam of something in his eyes that seemed almost like amusement.