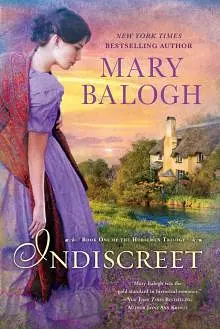

by Mary Balogh

“Well?” he said.

Everything about it was square and solid and on a grand scale. The house, built of gray stone, was classical in design with a pillared portico at the front. The inner park was built in a great square about it, its lawns shaded by ancient oaks and elms and beeches and dotted with clumps of daffodils and other spring flowers. There were no formal parterre gardens. The relatively short, straight graveled drive took them over a Palladian bridge across a river. It was all breathtakingly magnificent.

“It is lovely,” she said, feeling the inadequacy of her words even as she spoke them. Some things just could not be expressed in words. This was to be her home? She was to belong here?

He laughed softly.

Toby, sensing that they were nearing their journey’s end, sat up on the seat opposite and looked alert.

“We are expected,” her husband said. “By now my carriage will have been recognized. Mrs. Keach, my housekeeper, will doubtless be lining everyone up in the hall to receive their new mistress.”

He sounded mildly amused.

“All you need to do,” he said, “is nod graciously and smile if you wish and the ordeal will be over.”

All— Men were quite impossible, she thought.

He was quite right, of course. After he had helped her alight from the carriage and had escorted her up the marble steps and through the great double doors, she had no chance to look about her at the pillared hall, though she had an impression of size and magnificence. There was a silent line of servants on either side of the hall, men on one side, women on the other. Two dignified middle-aged servants, one man and one woman, stood alone together in the center of the hall. The man was bowing; the woman was curtsying.

They were the butler and the housekeeper, Horrocks and Mrs. Keach. Her husband presented her to them and she nodded and smiled and greeted them. She looked to either side, smiling. And then her husband had his hand on her elbow, said something about tea to Mrs. Keach, and would have steered her in the direction of the great pillared doorway that must lead to the staircase.

“Mrs. Keach,” she said, ignoring his hand, “I would be delighted to meet the women servants if you would introduce them to me.”

Mrs. Keach looked at her with approval. “Yes, my lady,” she said, and she led the way with great dignity to the end of the line and called each servant by name as they moved slowly along it. Her husband trailed after them, Catherine was aware. She concentrated on learning names and trying to associate them with their respective faces, though it would take her a while to remember them all, she supposed. She had a word with each of the servants. When they came to the end of the line and her husband reached for her elbow again, she turned toward the butler and asked him to perform the same duty for the menservants.

Finally she allowed herself to be steered toward the doorway and the grand staircase. Mrs. Keach went ahead of them.

“You will show her ladyship to her apartment, Mrs. Keach?” her husband said. “And make sure while she freshens up that someone waits outside to show her the way to the drawing room for tea when she is ready.”

“Yes, my lord,” the housekeeper murmured.

“I shall see you in a short while, then, my love,” he said, bowing over her hand as he relinquished it. He was looking amused again.

Her apartments, consisting of a bedchamber, a dressing room, and a sitting room, would probably hold her cottage twice over, she thought over the next half hour. The thought somewhat amused her. And also the memory of Toby’s trotting footsteps as he inspected the lines of servants with her. Her husband had scooped him up before he could follow her upstairs to her rooms. He was stretched out on the carpet before the fireplace when she entered the drawing room later but jumped up to meet her with a wildly wagging tail.

“Toby.” She stooped to pat him. “Is this all very strange to you? You will get used to it.”

“As will you,” a voice said from her right. He was standing by a window, though he came toward her and indicated the tea tray, which had been brought already.

She sat behind it to pour the tea. It was a beautiful room, she saw at a glance, with a coved and painted ceiling, a marble fireplace, and paintings in gilded frames on the walls. She guessed that most of them were family portraits. She was beginning to feel somewhat overwhelmed.

Her husband took his cup and saucer from her hands and sat down opposite her. “You really did not have to inspect the lines, you know,” he said. “You certainly were not expected to speak to every servant. But they were all charmed beyond words. You now have a houseful of slaves rather than servants, Catherine.”

“What is so funny?” she asked him, on her dignity. He was not looking just amused. He was actually grinning.

“You are,” he said. “You look rather like a child’s top, wound up and ready to start wildly spinning. You may relax. There has been no woman in this house since my mother died eight years ago. Everything runs perfectly, as you can see. Very little will be required of you. A mere token approval of the plans and menus Mrs. Keach will bring you.”

Ah, she understood. He thought she was incapable of running a household larger than the one she had had—or not had—at her cottage.

“You are the one who may relax, my lord,” she said, emphasizing his title since it was one little way she could always be sure of annoying him. She was feeling mortally insulted. “The household will continue to run smoothly for your comfort. I will speak with Mrs. Keach in the morning and together we will come to an amicable agreement about how the house is to be managed now that it has a mistress again.”

She enjoyed watching the smile being wiped clean from his face. But it was back soon enough, lurking behind his eyes as he regarded her in silence. He sipped on his tea.

“Catherine,” he said, “one of these days you are going to tell me who you are, you know. You are not at all daunted by all this, are you?”

“Not at all,” she said crisply. She had been wishing for a long time that she had told him everything that day she had given him her real name. There was really no reason why he should not have known. It was not as if she had been trying to prevent his crying off. She had hoped at the time that he would cry off. But now it was difficult to tell him.

“Catherine.” He had finished his tea and set down the cup and saucer on the table at his elbow. He shook his head and held up a staying hand when she picked up the teapot again. He looked at her in silence for a few moments and she thought he had nothing more to say. But he did. “Who is Bruce?”

Everything inside her seemed to turn over. She seemed to have been robbed of air. “Bruce?” Even her voice seemed to come from a distance.

“Bruce,” he repeated. “Who is he?”

How had he found out? How did he know that name?

“I have discovered,” he said, “that at least occasionally you talk in your sleep.”

She had started to dream about him again. About holding him and watching him just fade away into nothingness as she held him in her arms. She supposed it had been brought on by the fierce and unexpected desire for another child that had come with her marriage. Though there appeared to be no real chance of its happening anytime soon.

“I believe,” he said, and the coldness and arrogance she had seen in him on their first acquaintance were there again, “he is someone you once loved?”

“Yes.” The word was no more than a whisper. She should tell him now. Obviously he thought Bruce to be a man. But she could not tell him. How could she tell this cold stranger about the dearest love of her heart? She felt her vision blur and realized in some humiliation that her eyes had filled with tears.

“I cannot command your past affections,” he said. “Only your present and future ones. Though I am not sure I can ever command your affection. Your loyalty, then. I do command it, Catherine. I suppose a past love cannot be forgotten at will, but

you must understand that it is in the past, that I will not countenance any pining for what is gone.”

She hated him then. With a cold, intense passion.

“You are an evil man,” she hissed at him. Part of her knew she was being unfair to him, that he had misunderstood, that she should explain to him. But she was too deeply hurt to be fair. “I have married you because you left me with no choice. You will have my loyalty and my fidelity for the rest of my life, for what they are worth. Do not expect my heart too, my lord. My heart—every shadow and corner of it—belongs to Bruce and always will.”

She got to her feet and hurried from the room. Oh, yes, she was being dreadfully unfair, she knew. She did not care. If he thought to play the heavy-handed lord and master with her, then she would fight him with every weapon at her disposal, even unfairness. She half expected that he would come after her, but he did not. Toby was woofing excitedly at her heels, though. She hoped, as she hurried toward the staircase, that she could remember the way to her apartments.

17

THERE was a pianoforte in the drawing room that had not been played much in ten years, though it had always been kept in tune. He asked her to play it after dinner and she did so without argument and stayed there for longer than an hour. Probably, he thought, she was as relieved as he to have something to do that took away the necessity of making conversation. Though they had done remarkably well at dinner. It seemed that they could be good companions when they steered clear of personal matters.

He sat and watched her as she played. She was wearing a pale blue evening gown, neither fussy nor fashionable nor new. Her hair was dressed in its usual knot at the nape of her neck, even though he had made sure that a maid had been assigned to her to assist in her dressing. She looked very typically Catherine. She played self-consciously, though correctly, at first. Soon she lost herself in her music as she had in Claude’s music room that morning long ago—it seemed long ago. Beauty and passion came from the pianoforte and filled the room. It seemed almost impossible that one slim woman could be producing it. She could easily play professionally, he thought.

It felt strange to have her here at Stratton with him. She had obsessed him for those weeks at Bodley, the lovely and alluring—and elusive—Mrs. Winters. He had burned for her. He had schemed to win her. He had refused to take no for an answer. And now here she was with him in his house, his wife, his viscountess.

Even stranger was the fact that he felt a moment of triumph, almost of exultation. There was no triumph in what had happened. And no reason to exult. Their marriage was a mess, a nonevent. She loved and would always love a man named Bruce. He had even found himself racking his brains for any acquaintance of his with that name. But there was no one. Not even a corner or a shadow—how had she put it exactly? He frowned in thought. . . .

My heart—every shadow and corner of it—belongs to Bruce and always will.

And she had begun that impassioned speech by calling him an evil man. All because he had tried to establish a few ground rules with her, advising her that the past must be dismissed from her mind and the present take its place. What was evil about that?

She should have left him angry when she rushed from the room—and she did. She had also left him feeling shaken and bruised. Hurt. Though he was reluctant to concede that she had the power to hurt him.

Toby, who had been standing beside the pianoforte bench for a few minutes, slowly wagging his tail, had decided that there must be an easier way to attract his mistress’s attention. He leapt onto the bench and nudged her elbow with his nose.

“Toby.” She stopped playing and laughed. “Do you have no respect for Mozart? You are not accustomed to this sort of competition, are you? I suppose you need to go outside.”

Viscount Rawleigh got to his feet and strolled across the room toward them. She looked up at him, her eyes still laughing. He found himself changing plans abruptly. He had been about to inform her that there were footmen enough to take her dog outside whenever he needed to go, that it did not behoove the dignity of the Viscountess Rawleigh to be at the beck and call of a spoiled terrier.

“Maybe we could take a walk outside,” he said. “I wonder if the evening is as pleasant as the day has been.” What he was really wondering was how soon he was going to become the laughingstock among his servants. Belatedly he asserted his authority, his voice stern. “Get down from there, sir. The furniture in your new home is for viewing from floor level. Understood?”

But Toby was already prancing about his heels and yipping with excitement. And Catherine was laughing again. “You mentioned the W-word in his hearing,” she said. “It was not wise.”

He frowned down at the dog. “Sit!” he said curtly.

Toby sat and gazed at him with fixed, anticipatory stare.

“It must be your military background.” She was still laughing. “He will never do that for me.”

They were out on the terrace a few minutes later. She took his arm and they strolled all about the house while she examined it with interested eyes and looked about the park. It was a clear, moonlit night and not cold at all. Toby was dashing across the lawns, snuffling all around the trunks of the trees, acquainting himself with his new territory.

It would be bedtime by the time they went inside, he thought. Their first night home. The night that would set the pattern for all future nights, in all likelihood. Would he spend it in his own bed? By doing so he would be setting a precedent that would be hard to break. Was he willing to have such a marriage? A marriage in name alone?

It was ridiculous even to contemplate such a thing. She was his wife. He had desired her from his first sight of her. He had needs even apart from his attraction to her. Why should he go elsewhere to satisfy those needs? Besides, he had what was perhaps a regrettable belief in fidelity within marriage. He certainly was not prepared to live a celibate existence. He was no monk.

And was he to be inconvenienced merely because she still loved a man from her past?

He stopped walking at one corner of the house, close to the rose arbor, which had been his mother’s favorite part of the park.

“Catherine,” he asked her, “why did you cry?”

It was a foolish question to ask. He had not intended to begin this way. He would be just as happy to forget that night and its humiliation.

She stood facing him, looking up at him in the moonlight. God, but she was beautiful with her smooth dark hair, which looked more silver in this light, and her plain gray cloak. He could see from her eyes that she knew just exactly what he was talking about.

“For no particular reason,” she said. “I was— Everything was so new. I was a little overwhelmed. Sometimes emotion shows itself in strange ways.”

He was not sure that she spoke the truth. “You turned away from me,” he said.

“I—” She hunched her shoulders. “I did not mean to offend you. But I did.”

“Did I hurt you?” he asked. “Offend you? Disgust you?”

“No.” She frowned at him and opened her mouth as if to say more. But she closed it again. “No,” she said once more.

“Perhaps,” he said with unexpected and unwise bitterness, “you were comparing me—”

“No!” She closed her eyes and swallowed then looked down at her hands. He saw her shudder. “No. There was no comparison whatsoever.”

Which, in light of what she had said in the drawing room at tea, was a marvelous compliment indeed. He felt like a gauche, uncertain boy again and resented the feeling. He had become accustomed to thinking of himself as a tolerably skilled lover. Certainly the women with whom he had lain in the past several years had appeared well satisfied with his performance. But of course she loved the other man. Perhaps sexual skills were of little importance when one loved elsewhere.

“I am not prepared to conduct a celibate marriage,” he said.

She looked up,

startled. “Neither am I,” she said, and bit her lip. He wondered if she was blushing. It was impossible to tell in the moonlight. But her words were encouraging.

“If I come to your bed tonight,” he said, “will I be dismissed by tears again?”

“No,” she said.

He lifted a hand to smooth the backs of his fingers down one side of her jaw to the chin. “You know,” he said, “that I have always desired you.”

“Yes.” He felt her swallow.

“And I believe,” he said, “that though finer feelings are out of the question, you have desired me.”

“Yes.” It was a mere murmur of sound.

“We are married,” he said. “Neither of us wanted it but it happened. I will even take the blame upon myself. It was entirely my fault. But that is irrelevant now. We are married. Perhaps we can learn to rub along well enough together.”

“Yes,” she said.

“One thing.” He cupped her chin in his palm, holding her face up to his. But he knew it was unnecessary. She met his eyes as unflinchingly as she almost always did. “I cede your right to ‘my lord’ me when you want to set my teeth on edge—it is an admirable weapon and it would be unfair to deprive you of it since we will undoubtedly do our share of quarreling down the years. But I have a hankering to hear my name on your lips. Say it, Catherine.”

She gazed back into his eyes. “Rex,” she said.

“Thank you.” It was quite unclear to him why the sound of his own name spoken in her voice should cause a lurching of his insides. He had been too many nights without her, he supposed.

He closed the distance between their mouths and kissed her. Her lips were soft and warm and parted. They trembled against his, almost as if he had never kissed her before and they had never lain together. He felt the familiar soaring of his temperature. He had never known another woman who could ignite him so effectively with a mere kiss.