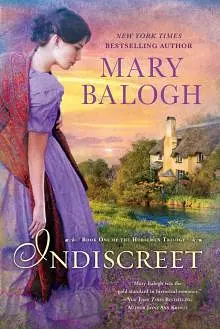

by Mary Balogh

She could not argue with that. She would not argue. She had needs too and she had always found him attractive.

His breathing had told her that he was asleep. She had not moved. She had not particularly wanted to be free of his weight or of his body, still joined to hers. But she had realized the emptiness of what had just happened. It had been something purely physical, something done purely for enjoyment. There was nothing wrong with enjoyment, especially when a man was taking it with his wife.

But there had been nothing more than that.

She had told him once that there was a person inside her body. That person now felt bereft. Was it enough, what had happened? Would it ever be enough?

He had slept for no longer than a few minutes. Then he had moved out of her and off her. But the loss of him had left her feeling cold and empty and a little frightened. And very lonely. She had turned onto her side, facing away from him, afraid to look into his eyes and see a confirmation of all she knew she would see there. For the first time ever she had a man with her in her bed. For the first time, apart from brief social visits, she had company in her cottage. She was married and would be looked after for the rest of her life.

She had never felt lonelier.

Absurdly, unfairly, she had waited for him to say something, to touch her, to comfort her. She had longed for his arms quite as much as she had longed for his body minutes before. And yet when he had spoken to her, she had shut him out. She had not quite realized she was crying until his hand came around her to touch her face. Instead of turning as she might have done and burying her face against his chest, she had buried it in the pillow, shunning him.

How could she have ached for comfort and shunned it all at the same time? She did not understand herself.

Yes, she did. There was no comfort to be had from him. And she would not shame herself by letting him know that what she needed, what she dreamed of now that dreams had so painfully been aroused in her again, was a relationship. Not necessarily love, that nebulous something that no one could quite explain in words but most young girls dreamed of anyway. She could live without love if she could only have kindness and companionship and a little laughter.

All she could have was this—this that had just happened to her. Wonderful beyond imagining while it was happening. Only a powerful reminder of her essential aloneness once it was over.

And then he had got off the bed and taken the candle and gone downstairs. She had thought at first that he was going to leave the house, perhaps never to come back. But of course he would not do that. He had married her for honor’s sake, for propriety’s sake. Honor and propriety would dictate that he stay at the cottage.

She lay on her back through the rest of the night, dozing and waking, knowing that she had made a terrible mistake. A mistake in marrying him, and a mistake in not accepting that marriage for what it was once the deed was done.

Long and tedious as the night was, she dreaded the coming of morning even more, when she must face him again.

• • •

HE woke, disoriented, when Toby jumped off his lap. Cramped muscles, a stiff neck, and general chilliness informed him that he was not in his own bed. And then his eyes opened.

Glory be, it was the morning after his wedding. And after his wedding night.

She was up. He caught the sound of the back door latch as she let the dog out. She did not come back immediately. She must have stepped outside with him as she had done the night before. Did she let one little—and poorly trained—terrier rule her life? he wondered irritably. It must be chilly, standing out there.

But it was far chillier in the kitchen. Especially with him there, he supposed. He remembered grimly the humiliation of having reduced her to tears with his lovemaking. That had never happened to him before. A shame it had had to happen for the first time with his wife.

He was making and lighting the fire with inexpert hands—even in the Peninsula he had always had servants, he reflected ruefully—when she came in. He was beginning to feel a certain respect for domestic servants.

“I could have done that,” she said quietly.

He turned around to look at her. With her simple blue wool dress and her hair in a knot at her neck, she looked like Mrs. Catherine Winters, widow, again.

“I do not doubt it,” he said. “But I have done it instead.”

Impossible to believe that he had known that body last night. It looked as slim and as lovely and as untouchable as ever. And quite as enticing. He set his jaw.

“I shall make some tea,” she said, moving past him with her eyes fixed on the kettle. “Would you like some toast?”

“Yes, please,” he said, clasping his hands behind him. He felt awkward, damn it all, like an unwelcome visitor. “Get down from there, sir.” It was a relief to be able to vent his spleen on some living creature.

Toby, on the rocker, cocked his ears, wagged his tail, and jumped down.

Lord Rawleigh became aware of his crumpled coat and breeches and of a general feeling of staleness about his person. He had brought a bag with him. It was time to wash and shave and dress for the arrival of his carriage and the beginning of the journey home.

With his wife. It was a strange, unreal thought.

His valet, had he been here, would have taken his clothes from the bag last night and set them out for him, making sure they were free of creases and lint. He had not thought of doing it for himself. Of course not. He had been too preoccupied with the desire to rush his bride upstairs and into bed as fast as possible.

Her movements were graceful and sure as she filled the kettle and set it over the fire to boil and as she sliced the bread ready to toast over the coals. She had not once looked into his eyes this morning. He was becoming more irritable by the minute.

“I shall go upstairs to wash and change,” he said. Was that where she washed? Or was it here in the kitchen? He had not noticed a washstand in her bedchamber.

“In the room opposite the bedchamber,” she said as if she had read his thoughts, busy spooning tea into the teapot. “If you would care to wait until the kettle has boiled, you may have some hot water.”

Damn! Of course, there were no servants to have carried up warm water for his wash and shave. How could she bear living like this? How would she adjust to life at Stratton? It was the first time he had thought of it. Would she be able to adjust? Would she be a fit mistress for his house? Well, if she was not, to hell with it. The house had run smoothly without a mistress for years.

Strangely enough they maintained a conversation through breakfast, which they ate while seated at the kitchen table. He told her about Lisbon, where he had spent a whole month at one time recovering from wounds. She told him about going to the stables at Bodley House to choose a puppy from a litter of five. She had chosen Toby because he was the only one who had stood on his stubby little legs and challenged her, squeaking ferociously at her for daring to invade his territory.

“Though he licked my hands and my face with equal enthusiasm when I picked him up,” she said with a laugh. “What else could I do but bring him home with me? He had stolen my heart.”

She was gazing into her teacup and obviously seeing the cheeky puppy Toby had been. She was smiling, her eyes dreamy and twinkling all at the same time. He would not mind at all, Lord Rawleigh thought, having one of those smiles directed his way one of these days instead of being wasted on a teacup. But the thought brought back his irritation. She had turned away from him last night and wept!

He pushed his chair back and got to his feet.

“The carriage will be here in little more than half an hour,” he said, drawing his watch from a pocket. “We should be ready to leave so that we may have as much daylight as possible for travel. It is a long journey.”

“Yes,” she said, and he became suddenly aware of her cup rattling down onto her saucer and her hand whippin

g away from it—so that he would not see how much it shook?

What now? Was the thought of leaving with him so dreadful? Or was it the thought of leaving here? The cottage had been her home for five years. And she had made it a cozy haven, he had to admit, however inconvenient he found it with its lack of servants.

He looked down at her, trying to form words that would show his sympathy for her feelings. Irritability vanished for a moment in shame that he was responsible for all this.

Would she really prefer to be staying here, alone again, living her life of dull and blameless routine and service to others? Single again? But there was no point to the preference or to his awareness of it and sympathy with her. They were married and she must come with him to Stratton. That was the simple reality.

She had got up too, without looking at him, and was pouring water from the kettle into a jug.

“I believe that will be enough,” she said, handing it to him. “There is cold water upstairs to be mixed with it, my lord.”

There was an awkward moment when she flushed and bit her lip and he felt a flashing of fury and perhaps too of pain. Then he turned and left the room, the jug of boiling water in his hand.

My lord.

She had married him yesterday. She had lain with him last night.

And she had wept afterward.

My lord.

• • •

MR. and Mrs. Adams—Claude and Clarissa—had come in the carriage. They were going to walk back home, they explained. Daphne had intended to come too, but she had felt bilious at breakfast and Clayton had had to assist her back to their rooms.

“The excitement of the past week or two has caught up to her,” Claude said with a smile.

“I do hope it is no more than that,” Catherine said, instantly concerned. Though truth to tell, she was glad of something on which to fix her mind and the conversation. There could be nothing more embarrassing than meeting the eyes of the brother and sister-in-law had been when they arrived unexpectedly and seeing the kindly laughter in Claude’s eyes and the well-bred speculation in Clarissa’s.

It must have been patently obvious from the blushes she had been quite unable to quell that the deed had been done last night.

“So do I,” Clarissa said. “I do not want the children becoming ill. I have urged Claude to send for the physician to see Daphne and to look at them, but he insists we wait.” She looked very unhappy.

Catherine touched her hand. She did not feel any deep affection for her new sister-in-law, but she had never doubted that Clarissa loved her children. And there were so many dangers to the survival of children, even if they successfully survived the birthing.

“I am sure it is just the excitement,” she said. “Daphne hardly stopped for breath all the time I was staying at Bodley.”

“Yes, I daresay you are right.” Clarissa smiled rather bleakly.

But the arrival of the carriage, of course, heralded the departure. The leaving of everything she had known and held dear for five years. Everything with which she had identified herself for that time. She had grown up here from foolish girlhood to a somewhat wiser maturity. She had known a certain peace and a measure of contentment here.

“Well, Catherine.” Her husband was standing in the open doorway. His coachman had carried out their bags already. All her furniture and most of her belongings were to be left behind for now. Claude and Clarissa had stepped outside and were standing on the path, ready to see them on their way.

She felt such a welling of panic suddenly that she thought for one moment she was going to crumple into a heap.

He was looking at her closely. “Five minutes,” he said, and he stepped outside and half closed the door behind him.

She went back into the kitchen and looked about her. Home. This had been the very center of her home. She had felt safe here. Almost happy. She crossed to the window and gazed out at her flowers and fruit trees, at the river beyond and the meadows and hills beyond that.

Her throat and her chest ached. The pain spread upward all the way behind her nose and pricked at her eyes. She blinked them firmly and turned away.

One last look around. The morning’s fire had been carefully put out. Toby was whining at her side and rubbing against her legs, begging to be petted. It was almost as if he knew that they were about to leave their home forever. She took up the embroidered cushion from the rocker and held it against her with both arms. She could not put it back. She had embroidered it herself in the early days, when her hands had needed occupation in order to distract her mind.

She left the kitchen and the house all in a rush, her chin up, a smile on her face. Her husband was waiting just outside the door. He took the cushion from her, drew her arm through his, and held it firmly to his side while walking her to the gate and the carriage.

“I am sorry to have kept you all waiting,” she said gaily. “I forgot something. Foolish of me. And it was only this old cushion, but—”

She was in Claude’s arms then, being hugged so tightly that there was no breath left for words.

“All will be well,” he was saying into her ear. “I promise you, my dear.”

Foolish words if she thought about them. What could he do to guarantee her happiness? But she felt enormously comforted and several stages closer to tears.

“Catherine.” Clarissa was hugging her too, with slightly less enthusiasm. “I do want us to be friends. I do.”

And then she was being handed into the carriage and Toby, nervous and excited, was leaping onto her lap and being invited sternly to get down—he jumped onto the seat opposite, ears cocked, tongue lolling, quite uncowed by the reprimand from his new master—and her husband was climbing in to take his seat beside her.

She kept her face averted, looking out of the far window as the carriage lurched into motion. It was ill-mannered not to wave to Claude and Clarissa, but she could not bear to look, to see her cottage disappear from her sight forever. She was gripping something tightly and realized that it was her husband’s hand. Had she reached for it, or had he taken hers? She could not recall. But she drew her hand away as unobtrusively as possible.

And then she had a thought and leaned forward to look back after all. “I forgot to shut the door,” she wailed.

Toby whined.

“It is safely shut and locked,” he said quietly. “All will be kept safe, Catherine, until we send for it.”

He spoke kindly enough. But he would not understand, of course, that it was not really thieves she was afraid of or the loss of her possessions. The possessions themselves were of little value. It was what they stood for that was lost forever. She had lost the only home she had made for herself. She had lost a little of herself.

Perhaps a great deal of herself.

She felt frightened and empty and diminished.

Her hand was in his again, she realized after a few minutes. She left it there. Somehow there was a measure of comfort in his touch.

• • •

CLAUDE took his wife back home via the postern door and the woods beyond. They walked silently side by side. He had offered his arm, but she dropped her own once they were through the door. He slowed his steps to match hers even though it would have suited him better to stride along in the direction of home.

She was the one to break the silence after several minutes. She stopped walking and gazed at him unhappily.

“Claude,” she said, “I cannot bear this any longer.”

“I am sorry.” He glanced down at the slippers she had worn, suitable for the carriage, perhaps, but not for the walk home. “I should have taken you by the driveway. Take my arm again.”

“I cannot bear it,” she said, ignoring his offered arm.

He dropped it. Perhaps he had known as soon as she spoke that she was not protesting the uneven ground underfoot. He looked at her and clasped his h

ands behind his back.

“We have not spoken to each other in more than two weeks,” she said, “except for meaningless civilities. You have not—you have kept to your own rooms for all that time. I cannot bear it.”

“I am sorry, Clarissa,” he said quietly.

She gazed at him uncertainly. “I would rather you ranted and raved at me,” she said. “I would rather that you struck me.”

“No, you would not,” he said. “That would be unpardonable. I would never forgive myself or expect you to forgive me. It would put an insurmountable barrier between us.”

“Is the barrier between us now surmountable, then?” she asked.

“I do not know,” he said after a lengthy pause. “It will need time, I believe, Clarissa.”

“How much time?” she asked.

He shook his head slowly.

“Claude, please.” She was looking up through the spring leaves on the branches above her. “I am sorry. I am so sorry.”

“Because our marriage has been soured?” he asked her. “Or because you almost ruined an innocent woman? If Rex had not returned, Clarissa, and if Daphne had not gone into such determined action, Catherine would have been in a difficult situation indeed. Would you have been sorry then? If I had agreed with you and had not sent for Rex, would you have been sorry? Or would you be gloating with righteousness along with our rector and his wife?”

“I had hoped for a match between Rawleigh and Ellen,” she said. “Mrs.—Catherine seemed to have ruined that hope. And it did seem that she had entertained him and been unpardonably indiscreet.”

“So,” he said quietly, “we are back where we started. Will you take my arm? The ground is rougher than I remember.”

She took his arm and then rested her forehead against his shoulder. “I cannot bear this coldness between us,” she said. “Can you understand how difficult it is to humble myself like this and plead for your forgiveness? It is not easy. Please forgive me.”