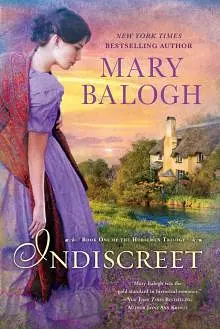

by Mary Balogh

“Sorry, old chap,” a bored and haughty voice said from behind her. “I reserved this set well in advance of this evening. Perhaps Mrs. Winters has the next one free for you.”

She turned rather sharply and placed her hand in Viscount Rawleigh’s outstretched one and allowed him to lead her onto the floor without even a backward glance at Sir Clayton. And she knew without a doubt—even though they were one of the first couples to take the floor and even though most eyes must be upon them—she knew that she was glad. That this was why she had come. That this was what she had waited for all evening.

“You were within a hairbreadth of giving away my waltz to my brother-in-law, Mrs. Winters,” he said, his dark eyes holding hers. They were standing facing each other, though not yet touching since the music had not begun. “I would have been very annoyed. You have never seen me annoyed, have you?”

“It would be better if I did not?” she said. “I would be reduced to a mass of quivering jelly? I think not, my lord. I know you were a cavalry officer during the war, but I am not one of your raw recruits.”

“I never engaged any of my raw recruits to waltz with me,” he said. “I would not so blatantly court scandal.”

She laughed despite herself and was rewarded with an answering gleam of amusement in his eyes.

“Ah, this is better,” he said. “You laugh all too rarely, Mrs. Winters. I wonder if there was a time when you laughed more freely.”

“One would be thought either insane or very immature if one went off into peals of glee at every suggestion of wit, my lord,” she said.

“I believe,” he said, ignoring her words, “there must have been such a time. Before you came to Bodley-on-the-Water. In God’s name, why this place? You must have been little more than a girl then. Let me guess. You had a strong romantic attachment to your husband and swore on his passing never to laugh again.”

Oh, dear Lord. Let the music start. She wanted no one playing guessing games with her past.

“Or else,” he said, “your marriage was such an unhappy experience that you retreated to a remote corner of the country and still have not learned to laugh freely again.”

She had come here tonight to enjoy herself. Her lips compressed. “My lord,” she said, “you are impertinent.”

His eyebrows shot up. “And you, ma’am,” he said, “try my patience.”

It was not an auspicious manner in which to begin a waltz, the dance she had just called romantic. But the music began at that moment and he moved a little closer to set one hand behind her waist and take her right hand in his. She set her left on his shoulder. He twirled her into the dance.

She had waltzed before. Many times. It had always been her favorite dance. And she had always imagined that it would be wonderful almost beyond bearing to waltz with a man who meant something to her. There was something so suggestive of intimacy and romance in the dance—there, that word again.

It was not romance she felt dancing with Lord Rawleigh. At first it was awareness, so raw and all-encompassing that she thought she might well faint from it. His hand at her waist burned into her. She felt his body heat from crown to soles, although their bodies did not touch. She could smell his cologne and something beyond that. She could smell the very essence of him.

And then she felt exhilaration. He was a superb dancer, twirling her confidently about the ballroom without missing a step and without colliding with any other dancer. She matched her steps to his and felt that she had never come so close to dancing on air before. She had never felt so wonderfully happy.

And finally she felt self-consciousness. She caught Mrs. Adams’s eyes fleetingly and unintentionally as that lady danced with her husband. There was a smile on Mrs. Adams’s face and steel in her eyes. And fury.

She had been waltzing, Catherine realized, as if no other moment existed beyond this half hour and as if no one else existed but her and the man with whom she danced. She suddenly became aware that they danced in a ballroom filled with other people and that there was indeed time beyond this half hour. A whole leftover lifetime to be lived here among these very people—with the exception of Viscount Rawleigh, who would go away very soon.

She wondered what her face and the motions of her body had revealed during the past fifteen or twenty minutes. And she looked up to see what his face revealed.

He was looking steadily down at her. “God, but I want you, Catherine Winters,” he said. The heat of his words was quite at variance with the languor in his eyes.

This was what those people who objected to the waltz meant, she thought. It was a dance that aroused passions that had no business being aroused. And she was to waltz with him again before supper?

“I do believe, my lord,” she said, “that you begin to repeat yourself. We have dealt with that matter before now. It is a closed book.”

“Is it?” he said, his eyes dropping for a brief moment to her lips. “Is it, Catherine?”

She knew that he was an experienced and masterly seducer. A rake. He was not the first she had met. He knew all the power the sound of her given name on his lips would have over her. And of course he was quite right. She felt touched by tenderness.

Which was quite ridiculous under the circumstances.

Instead of answering, she fixed her eyes on the diamond pin that was winking among the elaborate folds of his neckcloth and danced on.

“I am glad,” he said when the music finally drew to an end and he was returning her to her place, “you did not answer my last question, ma’am. I would have hated to be compelled to call you a liar. The supper dance. Do not grant it to anyone else. You would not enjoy having me annoyed with you.” He raised her hand to his lips and kissed her fingers before turning to stroll away.

She was going to have to leave before the supper waltz, she decided. She could take no more of this. All the careful work of years was being undone. It might take her five more years to regain the poise and peace she had known just a couple of weeks ago. Perhaps she would never regain them at Bodley-on-the-Water. There would be constant reminders. But she could not leave. The very thought was frightening—starting all over again with strangers. But even if she wanted to try it, she could not. She had to stay here for the rest of her life.

She had come to Bodley House with Reverend and Mrs. Lovering. Perhaps, she thought, they would be ready to leave early, as they sometimes were, though it was unlikely that they would forfeit supper for the sake of an early night. She looked for them without a great deal of hope. But they were nowhere to be found.

She discovered eventually, when she asked the butler, that the rector had been called away to the bedside of Mrs. Lambton, who was very low, and had left to take Mrs. Lovering home before going with Percy, Mrs. Lambton’s son, the five miles to their farm. They had left without her, Catherine realized, either because they had forgotten her or, more likely, because it was still early and they had assumed that she would want to stay and would find someone else to give her a ride back to the village at the end of the evening.

Anyone would, of course. Any number of the neighbors would be going through the village on their way home and would be happy enough to set her down at her cottage gate. Mr. Adams would call out a carriage in a moment to take her home. She had no reason to feel stranded. It was not even very far to walk, though it was a cloudy and dark night. Anyway, she did not like to walk alone at night. But she could not possibly ask anyone to drive her home this early unless she could invent some dreadful ailment in a hurry.

She was stuck at the ball until the end, it seemed.

She smiled as Sir Clayton approached to claim his set.

• • •

HE burned for her. He could not remember having been at the mercy of a tease before—if that was what Catherine Winters was. He was more inclined to think that she did not quite know her own mind. But however it was, it was having all the effect

she could have desired if she really was teasing.

He had to have her.

He was not at all sure he would be this obsessed if she had become his mistress after that first visit, as he had fully expected she would. He could not believe so. Surely if he had had her then and for the two weeks since then, he would be satisfied. Still desirous of her, perhaps. She was unusually lovely and appeared to have character to go along with the looks. But surely he would not still be as hot for her as he was now.

He even thought briefly of changing his intentions. There was nothing to stop him from offering her marriage if he so chose, he thought. But the idea was not given serious consideration. He did not want to be married. It was true that he had courted and betrothed himself to Horatia with great haste only three years ago, but that very experience had soured him. He had fallen in love with a woman who had soon thrown him over for a rake. He was that poor a judge of female character. There would have been nothing but misery for him if he had married before discovering the weakness of her character or the insincerity of her protestations of love. Before he married, he would have to meet the woman who was as much a part of his soul as he was.

And that, of course, was romantic nonsense.

No, he certainly would not offer marriage to Catherine Winters merely because it seemed there might be no other way of bedding her. Besides, he knew almost nothing about her. It would be sheer madness to marry a virtual stranger, lovely as she was.

But no amount of sensible thinking as he danced and conversed and waited impatiently for the supper set to begin could cool his ardor. He wanted her and by God he would have her if there was a way of doing so short of ravishing her.

It was with considerable annoyance, then—and something deeper than annoyance—that he greeted the fact that she was nowhere to be found as the gentlemen around him were taking their partners for the supper waltz.

“Ellen is free for this set, Rawleigh,” Clarissa said archly, coming up from behind him as he looked keenly all about. “Do let me take you to her.”

“Pardon me, Clarissa,” he said more sharply than he had intended, “but I am engaged to dance with her after supper—for the second time. I have reserved this set with someone else.”

“Oh? Who?” Her voice had sharpened too.

He was feeling too annoyed to dissemble. Besides, why should he? When he had found her, he would be waltzing with her for all to see. “Catherine Winters,” he said.

“Mrs. Winters?” she said. “Oh. She must be very gratified, Rawleigh, I am sure, at such a mark of attention. And this is the second time you are to dance with her?”

“Excuse me, Clarissa,” he said, moving away. She was clearly not in the ballroom. Or on the landing outside. Or in the drawing room, where a few elderly people were playing cards. Where was she hiding? Hiding from him? Had she escaped? Gone home? But he had been present when the Reverend Lovering had been called away. She had not gone with him. She had come with the rector and would have to wait for someone else to take her home at the end of the ball. Unless she had walked. Surely she had not been foolhardy enough to have done that alone. Where was she?

There was only one possibility he could think of. He went to look in the music room.

There was a certain amount of light coming through the French windows, across which the curtains had not been drawn. But apart from that she was in darkness. She sat on the pianoforte bench, facing the keyboard but not playing. The waltz music from the ballroom was loud even down here. She did not look up when he opened the door and stepped inside. He strolled across the room toward her.

“My dance, I believe,” he said.

“I never wanted this to happen,” she said.

“This?” He felt hope build. She had not wanted it to happen, but it was happening?

She did not answer him for a while. She ran the fingers of her left hand over the keys, though she did not depress them.

“I am five-and-twenty years old,” she said. “I have lived here for five years. I have made friends and acquaintances here. I have made a meaningful life here. I have made a home of my cottage. I have a dog to love and be loved by. I have been happy.”

“Happy.” He would have to quarrel with that word. “Was your marriage so intolerable that this life—this half-life you have been living—seemed a happy one, Catherine?”

“I have not given you leave to use my name,” she said.

“Retaliate by calling me Rex, then,” he said. “You want me as much as I want you.”

She laughed without humor. “Men and women are so different,” she said. “What I want is peace of mind and contentment.”

“Dullness,” he said.

“If you like.” She was not going to argue the point with him even though he stayed silent to give her the chance.

“Were you happy with your husband?” he asked.

Again she was silent for a while. “I do not cultivate either happiness or unhappiness,” she said. “The one does not last long enough and the other lasts too long. My marriage is not your concern. I am not your concern. I wish you would go back to the ballroom, my lord, and dance with someone else. Any woman there would be glad to dance with you.”

“I want to dance with you,” he said.

“No.”

“Why not?” He gazed down at her. Even the arch of her neck in the faint light from the window was elegant, alluring.

She lifted her shoulders. “I do not like the feeling,” she said.

“The feeling of being alive?” he asked. “You are a good dancer. You take the rhythm of the music inside yourself and allow it to move through you.”

“I do not like being observed,” she said. “It would be remarked upon too particularly if I danced with you for a second time. Your sister-in-law did not like it the first time. I have to live here. For a lifetime. I cannot afford to give rise to even a breath of gossip.”

He set one foot on the bench beside her and rested his forearm on his leg. “You do not have to stay here,” he said. “You can come away with me. I will find you a home somewhere where you will not have to worry about anyone’s opinion but mine.”

She laughed again. “A love nest,” she said. “With only one man to please. How very desirable.”

“It must have seemed desirable to you once,” he said, “when you married. Unless you married for a reason other than love. I somehow cannot imagine your doing so.”

“That was a long time ago,” she said. “Please don’t let anyone find us here together.” She drew a deep inward breath. “Please.”

“This is my dance,” he said. “Come and dance it with me.” He stretched out his hand to her and returned his foot to the floor.

“No,” she said. “It is too late to join the set now.”

“Here,” he said. “Dance with me here. The music is loud enough and there is quite sufficient open space and no carpet on the floor.”

“Here?” She looked up at him for the first time.

“Come,” he said again.

She set her hand slowly in his and got hesitantly to her feet. But when he set his arm about her waist and took her hand in his, she raised her other to his shoulder and they moved to the music, twirling about the darkened room in harmony together. She really was a good dancer. She followed his lead so that he felt no consciousness of drawing her with him and no fear of stepping on her feet.

They danced in silence. At first they danced correctly, the proper distance between them despite the positioning of their hands. But when he looked down at her and a turn brought the light onto her face, he could see that she danced with her eyes closed. He drew her closer until her thighs brushed his as they moved and he could feel the tips of her breasts against his coat. And then he drew her closer still until he turned her hand to hold it palm in against his heart. She leaned her forehead against his shoulder and her hand

slid farther about his neck.

The music stopped eventually and they stopped moving.

She was slim and supple and warm against him. She smelled of soap, far more enticing than any of the expensive perfumes with which any of his mistresses had ever doused themselves. He was afraid to move. He hardly dared breathe. If she was in some sort of a trance, he did not want to wake her.

But she lifted her head after a while and looked into his face. He could not see her expression clearly. But her body remained arched warmly into his. He lowered his head and kissed her.

This time her lips were parted too. He moved his tongue along her upper lip from corner to corner and back along the lower lip. She neither withdrew nor responded. She seemed totally relaxed, rather like a woman after love. Except that he had been cheated of the love, he thought ruefully as she drew back her head.

“You do that well,” she said. “I suppose you do everything well. Including seduction. No more, though. I am going to go.”

Later. There was going to be a later. He would not press the point now. This was enough for now. But when it happened, it would not be seduction. It would be with her full consent. Perhaps she did not even realize it yet.

“Come, then,” he said. “We must not wait down here until all the food is gone.”

“No,” she said. “I did not mean to the supper room. I am going home.”

“Who is taking you?” He frowned. “The Reverend Lovering has not returned, has he?”

“I—I have someone,” she said. “You see? I brought my cloak down with me.”

He did not look, but he gathered that it was lying on a chair.

“You do not lie well,” he said. “You were planning to walk home alone. Why were you sitting in here, then? Did you not have the courage to do it?”

“There is nothing to it,” she said. “There are no wild animals here and no footpads. There is nothing to fear.”