by Sarina Bowen

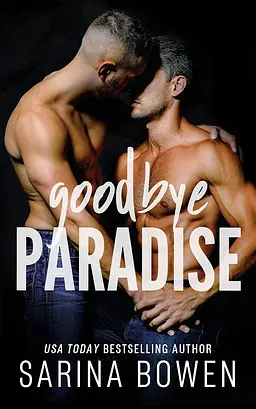

Goodbye Paradise

Sarina Bowen

Rennie Road Books

Contents

About GOODBYE PARADISE

The Gospel According to Josh

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

The Gospel According to Caleb

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

The Gospel According to Josh

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

The Gospel According to Caleb

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

JOSHUA ROYCE AND CALEB SMITH

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Also by Sarina Bowen

Acknowledgments

About GOODBYE PARADISE

Most people called it a cult. But for twenty years, Josh and Caleb called it home.

In Paradise, there is no television. No fast food. Just long hours of farm work and prayer on a dusty Wyoming ranch, and nights in a crowded bunkhouse. The boys of the Compound are kept far from the sinners’ world.

But Joshua doesn’t need temptation to sin. His whole life, he’s wanted his best friend, Caleb. By day they work side by side. Only when Josh closes his eyes at night can they be together the way he craves.

It can never be. And his survival depends on keeping his terrible desires secret.

Caleb has always protected Josh against the worst of the bullying at the Compound. But he has secrets of his own, and a plan to get away — until it all backfires.

Josh finds himself homeless in a world that doesn’t want him. Can Caleb find him in time? And will they find a place of safety, where he can admit to Josh how he really feels?

Warning: Contains a hot male/male romance, copious instances of taking the Lord's name in vain, and love against the kitchen counter. Previously published under a different title: In Front of God & Everyone.

Want to hear about all the latest books and discounts first? Join Sarina’s mailing list!

Part One

The Gospel According to Josh

One

Autumn

It should have been just another ordinary day of work and prayer, followed by more work, followed by more prayer. I had endured almost twenty years of those days already. But this one would turn out to be very different.

Also, I had a headache.

It was a crisp November afternoon, and we were out in the dry bean field, gathering in the crop. This was, hands down, my least favorite chore. Every fall we stood out here in the wind, fingertips sliced to bits by the sharp-edged bean hulls, the dried stems clattering in the breeze.

The throbbing at the base of my skull put an extra special twist on the whole experience. Hooray and hallelujah.

When I was a boy, we had a machine to hull the beans. I’d loved that crazy old diesel-fueled hunk of metal. The men had pitched the dried sheaves into one end, and the machine shook them senseless. Beans (and dust) came shooting into a hopper on one side. All the chaff was chucked out of the back, and the work went ten times as fast.

That machine wore out, though. And our Divine Pastor did not replace it. Why would he? It wasn’t his fingers bleeding on the beanstalks.

To entertain myself during our long days of labor, I often took over the compound in my mind — all two thousand acres of dusty Wyoming ranch land. The first thing I always planned (after ex-communicating all the assholes) was to invest in farm machinery, tripling the acreage for our cash crops. In my mind, I built us a shiny, efficient operation, diversified to minimize the risk of crop failure.

I enjoyed these fantasies while standing in that row of beans wearing torn trousers and hand-me-down boots a half size too small. Not a soul at the compound would ever listen to my plans, even if I were stupid enough to share them. I’d learned at an early age never to point out the foolishness of our leadership, or the inefficiencies of our operation.

Nobody wanted to hear this from the skinny kid with slow hands.

Beside me — just a few feet away — stood the other object of my fantasies. Caleb Smith was my best friend. We’d been close since we could barely toddle. There wasn’t a day of my life when I hadn’t counted the faded spray of freckles which stretched across his nose, or admired his slightly crooked smile.

While my elders might have little patience for my farming fantasies, the thoughts I had about Caleb were a punishable sin. He was the last one I saw before I closed my eyes at night and the first person I looked for when I opened them again in the morning.

Even now, as he leaned over the next plant, I coveted his broad chest and fine shoulders. He was quicker than I was at tearing the bean pods off the stalks and liberating the beans with his thumb. They dropped into his bucket with a satisfying clatter. My own slowness was probably due to my habit of stopping to admire Caleb’s rugged-looking hands.

At night, in my bunk all alone, Caleb’s hands made frequent appearances in all my best dreams.

Again, I pushed aside my sinful fantasies and tried to pick faster. It was my lot in life to be always two steps behind the other young men. For a long time I assumed that I would grow out of my dreamy nature. That I would someday be quick with farm tools and chores. But now that my nineteenth birthday had passed, it was obvious that my skills on the compound would never be praised.

I’d come to accept a lot of things about myself, actually. It’s just that I could never speak any of them aloud.

We had reached the end of a row. Caleb leaned down to yank his bucket around the end of it. But at the last second, he grabbed the handle of mine instead. Before I could even protest, he and my bucket had disappeared around the corner.

His bucket remained at my feet. And it was nearly full to the top.

With my face burning, I did the only conceivable thing. I hefted it, swinging it around the corner, setting it down at my feet, as if I’d picked all those beans myself.

Beside me, Caleb dropped more beans into the bucket formerly known as mine, his tanned hands threading into the dried sheaves the way I’d always wanted them to tangle in my hair.

Biting back a sigh, I grabbed a pod and cracked it in my hand. Discomfort and shame were my constant companions. Caleb covered for my mediocrity as best he could. My best friend had saved my backside too many times to count. And how did I repay him? With sinful, lusty thoughts.

Just another day in Paradise. That’s what they called this place where we lived and worked and prayed when they told us to.

Depressingly, the little kids of The Paradise Ranch didn’t even know that the rest of the world was not like this place. Sometimes I peered into the window of the little schoolhouse where the children were learning to read the Bible. (Only the Bible, and a book about our Divine Pastor. There weren’t any other texts. Poor little souls.)

Until the third grade, Caleb and I went to a real school in Casper. We all did. And man, I loved that place. Teachers pressed books into my hands and told me I was a wonderful student. School was my refuge.

But then, ten years ago, our Divine Pastor decided that the public school was a bad influence, because we came back to Paradise asking for Go-Gurt and Jell-O and Harry Potter. We came home corrupt, wanting things from the sinners’ world.

The elders did

n’t like it. So they built the schoolhouse (which is really just a drafty pole barn) and taught us exactly what they wanted us to learn, which is almost nothing.

I haven’t been off the Paradise Ranch since then.

Caleb sees the outside world, though. He’s the first born grandson of an elder, and therefore has a much better standing than I do. He has a valid birth certificate and — even better — a driver’s license. Once a week or so the elders send him out to the post office or to the feed store. Once they sent him to Wal-Mart, and he came back with lots of colorful stories of what he saw there. Bright television screens (we didn’t have any at Paradise, but we’d seen them when we were younger), crazy clothing, and all kinds of food in plastic packages.

There were no stories for me today, though. We couldn’t gossip on a bean harvest day, because there were too many others around to hear us. Though it was nice to be near Caleb. I could even hear the tune he kept humming under his breath.

Singing was not allowed. Caleb was very good at following the rules, but music was his downfall. Some of the compound trucks still had their radios. And since Caleb was handy with engines (and branding cattle, and the ancient tractor, and all the stuff I could never seem to manage) he was often asked to do mechanical maintenance. Even though it was risky, when he worked alone he would sometimes play the radio.

I couldn’t tell which tune he had stuck in his head today, because only little bits of it escaped. But even those breathy sounds made me want to lean in. I wished I could put a hand on his chest and feel the vibration when he hummed.

My head gave a brand new throb of pain, and I dropped some flaky pieces of chaff into the bucket, and had to fish them out.

* * *

The day ended before the never-ending bean field, which meant that we’d have to come back again tomorrow. Carrying my last ungainly bucket, I felt oddly exhausted. I stumbled, nearly spilling all those ill-gotten beans on the ground.

Ezra, the evilest of the bachelors, came running over — but not to help. Instead, he laughed in my face. “The little faggot can’t even carry the beans.”

Do not react, I cautioned myself.

Ezra used the word faggot whenever he felt like it, and not always on me. But I knew what it meant, and when he said it I always felt transparent.

That’s when Caleb arrived at my side, setting down his own bucket without a word. He just loomed there, a quiet wall of support.

Ezra grinned in that mean way he had. “Why do you help the little faggot, anyway? People gonna talk.”

My blood was ice, then. Our whole lives, Caleb had been taking heat for helping me. To hear such ugliness come from Ezra’s mouth terrified me. Because if, even for a second, people believed the things that he had just implied about Caleb? I would die of unhappiness. My sin was my own, and I couldn’t stand to see that ugliness tainting my friend.

Luckily, Caleb had both parentage and competence on his side. He always shook off Ezra’s taunts. When he spoke, his tone was mild. “I help everyone, Ezra,” he said. “Even you. Christian charity? You ever heard of that? You been sleeping through Sunday mass?”

At that, Caleb picked up both our buckets and carried them to the truck. He lifted them as if they weighed no more than two chickens.

* * *

Then it was dinner time, thank the Lord. My headache had spread down my neck and across my shoulders. For once in my stupid life, food did not even sound very appealing.

But I took my seat as usual at the end of a bench in our bunkhouse common room.

All the bachelors lived together. Usually around age sixteen, boys moved out of their family houses and into the bunkhouse. There were, at present, twenty-seven family houses on the compound, though the number went up by one or two houses each year. Each house held one man’s family, which meant they were crowded. Since each man had several wives, there were lots of children, too.

Teenage boys were very useful for farm work, of course. But the men did not like having their grown sons in the house. They took up too much space, for one. But also, it was not fit to have lusty young men share a roof with so many women. Since the girls in Paradise were married off at seventeen or eighteen, that meant that the youngest wives were often the same age as the bachelors.

Boys, on the other hand, could never marry as teenagers. The difficulty with polygamy was the imbalance. I had worked this out at a very young age, and naturally kept my conclusions to myself. But if a man deserves four or five wives, and women have boys fifty percent of the time, there are always far too many boys.

A boy in Paradise could expect to wait until he was in his twenties to marry. That gave the compound more than a decade of his farm labor while he tried desperately to prove himself worthy of his own wife and home.

Evil Ezra was twenty-four already, and probably the next in line to settle down. (I couldn’t wait to see him go, even though he wouldn’t go far.) In our bunkhouse there were twelve men over the age of twenty. Caleb turned twenty last month. I would turn twenty come springtime. There were a slew of teens, too.

Owing to the math, many of us would never get the chance to marry. But neither would we be welcome to stay on. Five years from now, quite a few of my bunkhouse roommates would be gone from Paradise. Some would run away, but many would be kicked out.

Nobody spoke of this practice, of course. There were many, many idiosyncrasies at Paradise that were not to be mentioned aloud, but the throwing away of half our young men was the ugliest one.

And here’s a sad thing—it often took Caleb and me a day or two to notice that someone had gone missing. We might hear a bachelor say at lunch, “where has Zachariah been today?”

And the question would be met with deep silence.

Then, a day or two later, a story would begin to circulate. Zachariah had been caught behind the tool shed with one of the daughters. Or, Zachariah had worshipped the devil. There was always a crime that was responsible for his downfall. And the crime did not need to sound original, or even plausible. Those who disappeared weren’t around to defend themselves. The ones who disappeared, however, were often the most dispensable among us. The weak and the slow. The ones whose labor would not be missed too badly.

The boys who disappeared looked a lot like me.

Caleb sat down on the bench beside me, folding his big hands in a typical gesture of patience. Whereas I was a pile of nerves, he was a calm giant. His body language was always serene. It was only when I looked into his eyes that I sometimes saw anxiety flickering there. That always gave me a start.

In those rare moments when I caught Caleb wearing a pained expression, he always looked away. Whatever it was that bothered him, it was something he did not want me to see.

And I always had a strong desire to comfort him, which would never be tolerated, of course.

When we were at prayer, I spent a good portion of my time praying for his safekeeping and happiness. The other portion was spent apologizing to God for my sinful preoccupation with him.

As they did before every dinnertime, daughters began to file into the room, each one of them bearing a pan or a dish. It was the families’ job to feed the bachelors three times each day. During an ordinary work week, mealtimes were the only moments when the daughters and the bachelors saw one another.

There was always supervision. Even now, Elder Michael stood at the head of the table, his serious eyes watching the proceedings, vigilant in the face of possible sin.

The swish of skirts continued. Since the daughters were made to dress alike, in long, roomy pastel dresses of identical design, all the swishes sounded the same.

A plate, napkin, and cutlery were placed in front of me. And I saw a particularly succulent chicken casserole land on the table as well. I kept my eye on it, even though someone quicker than I would probably reach it first, just after the prayer.

There was never quite enough to eat in the bunkhouse. More than two dozen hungry farm workers can put away an awful lot of food. None of us was

ever truly full. And nobody ever got fat. Only married men had that privilege. In the family houses, a man was king, with a small army of women and children who were all vying to be the one who pleased him best.

That’s what the Ezras and Calebs of the bunkhouse were working toward — their own little promised land.

One particular skirt swished to a stop behind us. “Evening Caleb,” a soft voice said.

I did not look up for two reasons. In the first place, I did not need my eyes to identify Miriam. She had been a part of our lives since I could remember. Our mothers were all friends. As children, the three of us had climbed onto the school bus together back when that was allowed.

Miriam and Caleb always seemed meant for one another, too. It wasn’t something we talked about. It just was. Caleb showed Miriam the same favor as he showed me, helping her whenever possible. He even had a special smile for Miriam, which I coveted. It was a smile that knew secrets.

The other reason I did not turn around to greet Miriam was as a favor to them both. My lack of notice helped them have a brief and whispered conversation. It was the only sort of conversation they could have, except on those rare occasions when there was some sort of party. A barn raising, or a christening, maybe. Otherwise, the daughters and the bachelors were kept apart.

“I need to speak with you,” she said in the lowest possible tone.

Caleb answered under his breath. “After supper I’ll change the oil on the Tacoma.”

With the message received, Miriam darted away without another word.

Elder Michael began to say a prayer, so I bowed my head. And then there were “amens” and the passing of dishes.

I did, in fact, secure a chunk of the chicken casserole, as well as a rice dish and some potato. This I forced myself to eat, even though I felt ill. Because you did not pass up food in Paradise.