Dedication

To Sarita, Bette, the Ladies of Ca/Az and the rest of the Rhine Whiners:

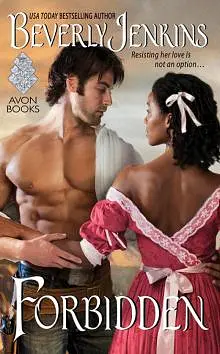

Rhine Fontaine is finally here. Enjoy!

Contents

Dedication

Prologue

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Dear Readers

About the Author

By Beverly Jenkins

Copyright

About the Publisher

Prologue

Georgia 1865

Wearing the blue uniform of the Union Army, Rhine Fontaine tethered his horse to the post and surveyed the charred piles of rubble of the house that once anchored the largest plantation in the county. It had also been his home. The sight of the destruction pleased him even though the bitter memories of his life there would follow him to the grave. The former two-story mansion with its Romanesque columns, wide front porch, and well-kept grounds had been set afire by his great aunt Mahti. She’d died in the flames along with his crippled, bed-ridden father, Carson Fontaine, who’d ruled his three hundred slaves with all the cruelty of a medieval king. Rhine hoped Carson was rotting in hell, but he mourned Mahti. She’d raised him, loved him, and helped him try and make sense of the harsh unfeeling world he’d been born into. With her gone, he and his younger sister Sable were the last living ties to their mother, Azelia, the descendant of an enslaved African queen. Rhine had been so young when Azelia died he could no longer recall her face, voice, or touch, and that, too, fed his bitterness. Slavery had been an abomination. Rhine hated it and this place so deeply that were he not seeking information on Sable’s whereabouts, he would never have come back.

He walked past the mansion’s remains to see if the rows of slave cabins were still out back and maybe find someone with news of Sable. Although the war was over and slavery was dead, many of the enslaved had chosen to remain with their masters. He couldn’t begin to understand their thinking nor did he judge, because he’d made what some would consider an equally unthinkable choice.

The cabins were there but in such terrible disrepair he doubted anyone lived in them anymore. Entire sections of the wooden walls were gone and many had no roofs. Weeds had grown tall enough to fill doorways, and as he stood in the eerie silence memories flowed back of slave children running and playing after a long day in the fields; their mothers cooking and mending, their fathers tending the small gardens that held beans, corn, yams, and collards to supplement the lean rations Carson grudgingly supplied. Those remembrances also brought back the sounds of mothers screaming helplessly while some of those same children were dragged off and sold.

From behind him a woman’s voice snarled, “There’s nothing left to steal here, Yankee, so, get off my land.”

He turned to see his father’s wife, Sally Ann Fontaine, standing in the doorway of one of the dilapidated cabins. Her ragged dirty gown, unkempt hair, and shoeless feet were shocking. The last time he’d seen her she’d been queen to Carson’s king. Now she looked worse than any of the slaves.

“Hello, Mrs. Fontaine.”

She studied him for a brief moment before recognition widened her brown eyes. “You! Where’s my Andrew?”

Andrew was his half brother. They’d gone to war together to fight for the Confederacy. “I don’t know. After the first battle, Drew deserted. Said he was heading west.”

“You’re lying!” And as if the hope of her son’s return was the only thing keeping her sanity intact, she leapt upon him screaming obscenities and pounding him with ineffectual fists. “No, you lying bastard! Where’s my son!”

He grabbed her wrists. “I don’t know.” And he didn’t. He also didn’t remind her that she and Drew had been estranged when they rode off to war because Drew refused to treat the slaves the way their father did.

As she crumbled and began weeping, he released her wrists and asked, “Have you seen my sister Sable?”

The tears stopped and the hate in her eyes seared him. “She ran off the morning after that old witch Mahti set fire to the house. Heard she was in one of the camps, so I sent a man to bring her back, but he said she’d taken up with some fancy French Black who refused to hand her over.”

Rhine assumed she was referencing Major Raimond LeVeq. When Rhine last saw his sister a year ago, he’d already switched his allegiance to the Union army, and she’d been a laundress in a contraband camp. LeVeq, a ranking officer at the camp, had been taken by his beautiful sister. Sadly, after only a few days Rhine’s unit had moved on and he’d had to leave Sable behind. Hearing that LeVeq had kept her out of Sally Ann’s clutches pleased him, but he had no idea where she was now. He also wondered about the fate of his half sister, Sally Ann’s daughter, Mavis.

“What are you doing in a fancy Yankee uniform?” Sally Ann asked.

Rhine didn’t reply. As the silence lengthened, she offered a bitter chuckle. “Passing again, are you?”

Rhine’s ivory skin, jet black hair, and green eyes made it easy for him to pass as someone he wasn’t. He was ten years old when he first realized he could do it successfully. In his role as Andrew’s slave, he’d accompanied the Fontaine family to a hotel in Atlanta. When their father Carson walked into the hotel’s restaurant and saw Rhine eating at the table with Andrew instead of in the back with the other slaves, he waited until they returned home and whipped Rhine until he bled. Ten-year-old Andrew had been whipped as well, but not as severely.

In a voice dripping with disgust, Sally Ann sneered, “Andrew turns his back on his race, and you turn your back on yours. What a wretched pair you are. Get off my land and don’t ever come back.”

Riding away, Rhine trusted that the old African queens whose blood ran in his veins would reunite him with Sable in the near future. With that belief settled firmly in his heart, he headed to his own future; one he planned to live out as White.

Chapter One

Denver

Spring 1870

“Stop him!” Eddy Carmichael screamed, scrambling to her feet from the mud. The man who’d snatched her purse and shoved her down was now running away down the dark Denver street. Taking off in pursuit, she called for help, but there were no policemen about and the few people on the walks nearby gave her no more than a passing glance. Up ahead, the thief turned a corner. Not wanting to lose him, she ran faster, but by the time she reached the spot, he’d disappeared. Frantically casting about for clues as to his whereabouts, she saw nothing. Anger turned to frustration and then to despair. Inside the purse had been her paltry month’s pay and the train ticket to California she’d purchased less than an hour ago. She’d been saving for the passage for months in hopes of starting a new life in San Francisco. Now, penniless, angry, her skirts and cloak covered with mud, she set out for home.

Eddy dreamed of owning her own restaurant. It was a common belief that women like her, the descendant of slaves, had no right to dream. Yet, she knew from the articles she’d read in the newspapers that members of the race were pursuing theirs in spite of the disenfranchisement being ignored by Congress and the bloody lawlessness of Redemption ravaging the South. Colleges were being built, land was being purchased, and across the nation Black owned

businesses were springing up like columbines in the spring. At the age of twenty-seven and unmarried, Eddy saw no such opportunities for herself in Denver, and now thanks to the thief those dreams were in peril.

Her home was a room she rented above a laundry owned by her landlady, Mrs. Lucretia Hampton. Eddy had been so sure of leaving town, she’d already given the woman notice and the new tenant was due to move in tomorrow afternoon. Although Mrs. Hampton would show concern over Eddy being robbed, the laundress was first and foremost a businesswoman and would likely not alter the agreement.

Putting her key into the door lock of her room, Eddy stepped into the darkness. As always, the acrid scent of lye wafting up from the laundry below filled the air. The room was so tiny even a mouse would have difficulty turning around, but on her meager salary it was all she could afford. Having worn the mantle of poverty since the death of her parents twelve years ago, she was grateful to have it. Making her way through the shadows over to the pallet that served as her bed, she struck a match and set the flame against the stub of candle in the old tin saucer that sat atop a battered wooden crate. While the wavering light filled the room, she removed her mud-stained cloak. Rather than attempt to clean it with the small bit of water in her basin, she hung it on the nail protruding from the back of the door with the hope that once the mud dried it would be easier to remove. She put her last pieces of kindling into the hearth. The resulting heat would be minimal but at least the flames held beauty, another element her life lacked. Warming her hands, she thought about her plight. She supposed she could remain in Denver and start saving again. Choosing that route meant finding another room to rent and a new job, because she’d given her employer notice, too. Six months ago, the hotel where she’d worked for the past three years as a cook had been purchased by a new owner whose first act had been to remove Eddy and every other person of color from the kitchen. He offered her a new job scrubbing floors for less money. The demotion was both infuriating and humiliating, but knowing how blessed she was to still have employment, she’d swallowed her anger and scrubbed the floors until they shone. Even then, he constantly found fault with her work and routinely docked her pay for what he termed inferior effort. She knew for a fact he’d never offer her the job back, and there was no way she’d be able to rent another room without one.

She ran her hands over her eyes and sighed. She didn’t want to stay in Denver, not even for another day. Her future lay elsewhere and she knew that as sure as she knew her name, but how could she could get the money for another ticket? Mrs. Hampton didn’t give loans. The Colored community was small and most were as pinched by poverty as she. Those who weren’t certainly wouldn’t loan her money even if she had the gall to ask. Her only relative in the city was her younger sister Corinne, and asking her for money made about as much as sense as asking the new owner of the hotel. After the deaths of their mother Constance and teamster father Ben in a blizzard, Eddy did everything she could to provide for herself and sister; she took in laundry, cooked for the wealthy, looked after their children, and swept their floors. But her beautiful baby sister chose to fall back on her looks and figure and took up with a pimp in the city’s red-light district. Although the pimp was long gone, Corinne still resided there along with her two young daughters. Eddy knew her sister would laugh in her face for having the audacity to ask for money. Corinne had nothing but derision for Eddy’s desire to better her life, but Corinne was her last resort. It was too late to pay her a visit at the moment, but she’d planned to stop by on her way to the station in the morning to say good-bye to her nieces anyway. Now, her visit would be about something different entirely.

“At least I won’t have much to pack,” she said softly. She’d sold what little possessions she’d had in order to help pay her rent and purchase the train ticket. What remained was her mother’s locket, a cast iron skillet, her small cookstove brazier, and a few meager changes of clothing. She had nothing else. Were she not so accustomed to having to claw her way through life, she might have collapsed and wept, but being made of sterner stuff, she’d learned long ago that weeping changed nothing.

The following morning, Eddy gathered her things, took a bittersweet look back at the place she’d called home, and closed the door. After handing Mrs. Hampton the key and being told, “Godspeed,” she set off. Her clothing and the skillet were stuffed in an old carpetbag and the cookstove was balanced on her head. It was a chilly April morning and the city was just coming to life.

Most of the residents of the red-light district were sleeping off last night’s excesses, so the streets were quiet. The seedy area with its cribs, saloons, and bawdy houses looked tired and worn-out under the dawning light of day. Eddy guessed her sister would be asleep, too, and would probably not welcome the early morning visit, but it couldn’t be helped. Setting the cookstove on the ground by her feet, she knocked on the shack’s door.

Her twelve-year-old niece Portia answered the knock and her dark eyes brightened. “Aunt Eddy!”

She threw herself into Eddy’s arms, and Eddy held her tight and kissed her brow. Eddy loved the girls and hated the circumstances they were being raised under. She dearly wanted to offer them a home with her, but going from a destitute mother to a destitute aunt served no one. Although Corinne swore she loved her daughters, Eddy worried about them constantly, especially now that they were growing into young ladies.

Portia’s baby sister, ten-year-old year Regan, appeared and also met Eddy’s appearance with joy. Both girls had inherited their mother’s great beauty. Eddy assumed Corinne knew who their fathers were but had never shared the identities with Eddy.

Regan asked, “Did you come to spend the day with us, Aunt Eddy?”

The hope in her eyes twisted Eddy’s heart. “No, sweetie. I came to talk to your mama. Is she sleeping?”

Regan nodded. “And if we wake her up she’ll whip us. Won’t she, Portia?”

Portia didn’t respond verbally but the tense set of her chin affirmed it.

As if cued, the angry Corinne entered the room belt in hand and snapped, “How many times have I told you not to wake me up?” Seeing Eddy, she paused. “Oh, it’s you. What do you want?”

“My purse was stolen yesterday. My train ticket to California was inside.”

“So?”

Eddy held onto her patience. “I came to see if I could borrow enough to buy another. I’ll pay you back once I’m settled.”

“Why are you going to California?”

“To look for a job. There’s nothing here for me.”

Portia looked mortified. “You’re leaving Denver, Aunt Eddy?”

Eddy knew she should have told them about California before now, but she and Corinne were like tinder and matches, so she kept putting the visit off. “I’m hoping to,” she said softly. “I’ll come back to see you and Regan as soon as I can. I promise.”

Portia, so stoic for someone her age, raised her chin stiffly. “Okay.”

Corinne said coolly, “Portia, since I’m up, go strip the sheets off my bed, and pump some water so we can start the wash.”

“Yes, Mama.” She hurried from the room and disappeared into the back.

Regan laced her thin arms around Eddy’s waist and pressed herself close. She whispered through her tears. “Please don’t leave Aunt Eddy. Please.”

Eddy felt awful.

“Regan, stop that sniveling and go help your sister.”

“Yes, Mama.”

Eddy caressed her cheek in good-bye and Regan left the room.

“You didn’t have to be so mean, Corinne.”

“Don’t tell me how to raise my children. When you get your own, you can treat them any way you like. And, I don’t have any money for you or your highfalutin dreams. I told you years ago, you’d make more money down here than you’d ever make uptown. You had the bosoms and the looks, but no, you thought you were too goo

d.”

“No, I didn’t want to become a whore, Corinne.”

“Yet here you are begging help from a whore.”

“I’m here begging help from my sister.” Corinne’s legendary allure had faded; too many men, too much whiskey, too much hardship. Now, instead of features that could’ve launched ships like the fabled Helen of Troy, she looked as tired and worn-out as any other women of her profession. Eddy was saddened by that.

“I have nothing for you. Guess you and your dreams will have to walk there.”

“I guess so.” Eddy thought back on how much she once loved her sister, the giggles they’d shared in their bedroom at night, the way they’d played as girls, and the sense of family their parents always tried to instill. Standing before her now in a ratty, faded green wrapper was a woman she didn’t know and it broke Eddy’s heart. “Good-bye, sister. I’ll write when I get settled.”

“Fine.”

Eddy left.

Setting aside the sadness of the painful visit, Eddy set out to see an old friend of her parents, an aging teamster named Mr. Biggins. He rented wagons for tradesmen and sometimes for people traveling. It was possible he knew of someone going west who might let her tag along in exchange for her cooking skills. Thanks to her father, she also knew her way around wagons and animals. Although it had been years since she’d driven a team, it wasn’t a skill one forgot.

When she entered his establishment his old blue eyes brightened in much the same way her nieces had.

“Morning, Miss Eddy, you finally coming around to accept my marriage proposal?”

Chuckling, she said, “No, Mr. Biggins, but I do need your help.”