Preface

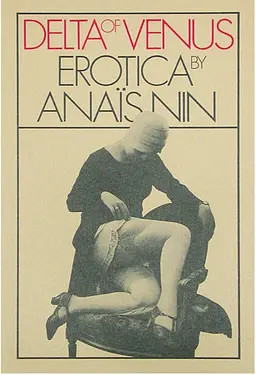

Delta of Venus

Partly of Spanish origin, Anaïs Nin was also of Cuban, French and Danish descent. She was born in Paris and spent her childhood in various parts of Europe. Her father left the family for another woman, which shocked Anaïs profoundly and was the reason for her mother to take her and her two brothers to live in the United States. Later Anaïs Nin moved to Paris with her husband, and they lived in France from 1924 to 1939, when Americans left on account of the war. She was analysed in the 1930s by René Allendy and subsequently by Otto Rank, with whom she also studied briefly in the summer of 1934. She became acquainted with many well-known writers and artists, and wrote a series of novels and stories.

Her first book – a defence of D. H. Lawrence – was published in the 1930s. Her prose poem, House of Incest (1936), was followed by the collection of three novellas, Winter of Artifice (1939). The quality and originality of her work were evident at an early stage but, as is often the case with avant-garde writers, it took time for her to achieve wide recognition. The international publication of her Journals won her new admirers in many parts of the world, particularly among young people and students. Her novels, Ladders to Fire, Children of the Albatross, The Four-Chambered Heart, A Spy in the House of Love and Seduction of the Minotaur, were first published in the United States between the 1940s and the 1960s, and eventually gathered in Cities of the Interior. She also wrote a collection of short stories, Under a Glass Bell. In the 1940s she began to write erotica for an anonymous client, and these pieces are collected in Delta of Venus and Little Birds (both published posthumously). Penguin also publish A Woman Speaks, a collection of lectures and interviews; Journal of a Wife, the third volume of The Early Diary of Anaïs Nin, 1923–1927; In Favour of the Sensitive Man and Other Essays; and, most recently, The Early Diary 1927–1931, which is the fourth volume of her diary. Henry and June, a chronicle of her passionate involvement with Henry Miller and his wife June Mansfield, and Incest are the new volumes of the ‘unexpurgated diary’ of Anaïs Nin, distinguishable from her previously published volumes by the references to both her husband and her love life. Her books have been translated into twenty-six languages around the world.

During her later years Anaïs Nin lectured frequently at universities throughout the USA. In 1973 she received an honorary doctorate from Philadelphia College of Art and in 1974 was elected to the National Institute of Arts and Letters. She died in Los Angeles in 1977.

ANAÏS NIN

DELTA OF VENUS

CONTENTS

Preface

The Hungarian Adventurer

Mathilde

The Boarding School

The Ring

Mallorca

Artists and Models

Lilith

Marianne

The Veiled Woman

Elena

The Basque and Bijou

Pierre

Manuel

Linda

Marcel

Preface*

[April, 1940]

A book collector offered Henry Miller a hundred dollars a month to write erotic stories. It seemed like a Dantesque punishment to condemn Henry to write erotica at a dollar a page. He rebelled because his mood of the moment was the opposite of Rabelaisian, because writing to order was a castrating occupation, because to be writing with a voyeur at the keyhole took all the spontaneity and pleasure out of his fanciful adventures.

[December, 1940]

Henry told me about the collector. They sometimes had lunch together. He bought a manuscript from Henry and then suggested that he write something for one of his old and wealthy clients. He could not tell much about his client except that he was interested in erotica.

Henry started out gaily, jokingly. He invented wild stories which we laughed over. He entered into it as an experiment, and it seemed easy at first. But after a while it palled on him. He did not want to touch upon any of the material he planned to write about for his real work, so he was condemned to force his inventions and his mood.

He never received a word of acknowledgment from the strange patron. It could be natural that he would not want to disclose his identity. But Henry began to tease the collector. Did this patron really exist? Were these pages for the collector himself, to heighten his own melancholy life? Were they one and the same person? Henry and I discussed this at length, puzzled and amused.

At this point, the collector announced that his client was coming to New York and that Henry would meet him. But somehow this meeting never took place. The collector was lavish in his descriptions of how he sent the manuscripts by airmail, how much it cost, small details meant to add realism to the claims he made about his client’s existence.

One day he wanted a copy of Black Spring with a dedication.

Henry said, ‘But I thought you told me he had all my books already, signed editions?’

‘He lost his copy of Black Spring.’

‘Who should I dedicate it to?’ said Henry innocently.

‘Just say “to a good friend”, and sign your name.’

A few weeks later Henry needed a copy of Black Spring and none could be found. He decided to borrow the collector’s copy. He went to the office. The secretary told him to wait. He began to look over the books in the bookcase. He saw a copy of Black Spring. He pulled it out. It was the one he had dedicated to the ‘Good Friend’.

When the collector came in, Henry told him about this, laughing. In equally good humour, the collector explained: ‘Oh, yes, the old man got so impatient that I sent him my own copy while I was waiting to get this one signed by you, intending to exchange them later when he comes to New York again.’

Henry said to me when we met, ‘I’m more baffled than ever.’

When Henry asked what the patron’s reaction to his writing was, the collector said, ‘Oh, he likes everything. It is all wonderful. But he likes it better when it is a narrative, just storytelling, no analysis, no philosophy.’

When Henry needed money for his travel expenses he suggested that I do some writing in the interim. I felt I did not want to give anything genuine, and decided to create a mixture of stories I had heard and inventions, pretending they were from the diary of a woman. I never met the collector. He was to read my pages and to let me know what he thought. Today I received a telephone call. A voice said, ‘It is fine. But leave out the poetry and descriptions of anything but sex. Concentrate on sex.’

So I began to write tongue-in-cheek, to become outlandish, inventive, and so exaggerated that I thought he would realize I was caricaturing sexuality. But there was no protest. I spent days in the library studying the Kama Sutra, listened to friends’ most extreme adventures.

‘Less poetry,’ said the voice over the telephone. ‘Be specific.’

But did anyone ever experience pleasure from reading a clinical description? Didn’t the old man know how words carry colors and sounds into the flesh?

Every morning after breakfast I sat down to write my allotment of erotica. One morning I typed: ‘There was a Hungarian adventurer…’ I gave him many advantages: beauty, elegance, grace, charm, the talents of an actor, knowledge of many tongues, a genius for intrigue, a genius for extricating himself from difficulties, and a genius for avoiding permanence and responsibility.

Another telephone call: ‘The old man is pleased. Concentrate on sex. Leave out the poetry.’

This started an epidemic of erotic ‘journals’. Everyone was writing up their sexual experiences. Invented, overheard, researched from Krafft-Ebing and medical books. We had comical conversations. We told a story and the rest of us had to decide whether it was true or false. Or plausible. Was this plausible? Robert Duncan would offer to experiment, to test our inventions, to confirm or negate our fantasies. All of us needed money, so we pooled our stories.

I was sure the old man knew nothing about the beatitudes, ecstasies, dazzling reverberations of sexual encounters. Cut out the poetry was his message. Clinical sex, deprived of all the warmth of love – the orchestration of all the senses, touch, hearing, sight, palate; all the euphoric accompaniments, background music, moods, atmosphere, variations – forced him to resort to literary aphrodisiacs.

We could have bottled better secrets to tell him, but such secrets he would be deaf to. But one day when he reached saturation, I would tell him how he almost made us lose interest in passion by his obsession with the gestures empty of their emotions, and how we reviled him, because he almost caused us to take vows of chastity, because what he wanted us to exclude was our own aphrodisiac – poetry.

I received one hundred dollars for my erotica. Gonzalo needed cash for the dentist, Helba needed a mirror for her dancing, and Henry money for his trip. Gonzalo told me the story of the Basque and Bijou and I wrote it down for the collector.

[February, 1941]

The telephone bill was unpaid. The net of economic difficulties was closing in on me. Everyone around me irresponsible, unconscious of the shipwreck. I did thirty pages of erotica.

I again awakened to the consciousness of being without a cent and telephoned the collector. Had he heard from his rich client about the last manuscript I sent? No, he had not, but he would take the one I had just finished and pay me for it. Henry had to see a doctor. Gonzalo needed glasses. Robert came with B. and asked me for money to go to the movies. The soot from the transom window fell on my typing paper and on my work. Robert came and took away my box of typing paper.

Wasn’t the old man tired of pornography? Wouldn’t a miracle take place? I began to imagine him saying, ‘Give me everything she writes, I want it all, I like all of it. I will send her a big present, a big check for all the writing she has done.’

My typewriter was broken. With a hundred dollars in my pocket I recovered my optimism. I said to Henry, ‘The collector says he likes simple, unintellectual women – but he invites me to dinner.’

I had a feeling that Pandora’s box contained the mysteries of woman’s sensuality, so different from man’s and for which man’s language was inadequate. The language of sex had yet to be invented. The language of the senses was yet to be explored. D. H. Lawrence began to give instinct a language, he tried to escape the clinical, the scientific, which only captures what the body feels.

[October, 1941]

When Henry came he made several contradictory statements. That he could live on nothing, that he felt so good he could even take a job, that his integrity prevented him from writing scenarios in Hollywood. At the last I said, ‘And what of the integrity of doing erotica for money?’

Henry laughed, admitted the paradox, the contradictions, laughed and dismissed the subject.

France has had a tradition of literary erotic writing, in fine, elegant style. When I first began to write for the collector I thought there was a similar tradition here, but found none at all. All I had seen was shoddy, written by second-rate writers. No fine writer seemed ever to have tried his hand at erotica.

I told George Barker how Caresse Crosby, Robert, Virginia Admiral and others were writing. It appealed to his sense of humor. The idea of my being the madam of this snobbish literary house of prostitution, from which vulgarity was excluded.

Laughing, I said, ‘I supply paper and carbon, I deliver the manuscript anonymously, I protect everyone’s anonymity.’

George Barker felt this was much more humorous and inspiring than begging, borrowing or cajoling meals out of friends.

I gathered poets around me and we all wrote beautiful erotica. As we were condemned to focus only on sensuality, we had violent explosions of poetry. Writing erotica became a road to sainthood rather than to debauchery.

Harvey Breit, Robert Duncan, George Barker, Caresse Crosby, all of us concentrating our skills in a tour de force, supplying the old man with such an abundance of perverse felicities, that now he begged for more.

The homosexuals wrote as if they were women. The timid ones wrote about orgies. The frigid ones about frenzied fulfillments. The most poetic ones indulged in pure bestiality and the purest ones in perversions. We were haunted by the marvelous tales we could not tell. We sat around, imagined this old man, talked of how much we hated him, because he would not allow us to make a fusion of sexuality and feeling, sensuality and emotion.

[December, 1941]

George Barker was terribly poor. He wanted to write more erotica. He wrote eighty-five pages. The collector thought they were too surrealistic. I loved them. His scenes of lovemaking were disheveled and fantastic. Love between trapezes.

He drank away the first money, and I could not lend him anything but more paper and carbons. George Barker, the excellent English poet, writing erotica to drink, just as Utrillo painted paintings in exchange for a bottle of wine. I began to think about the old man we all hated. I decided to write to him, address him directly, tell him about our feelings.

‘Dear Collector: We hate you. Sex loses all its power and magic when it becomes explicit, mechanical, overdone, when it becomes a mechanistic obsession. It becomes a bore. You have taught us more than anyone I know how wrong it is not to mix it with emotion, hunger, desire, lust, whims, caprices, personal ties, deeper relationships that change its color, flavor, rhythms, intensities.

‘You do not know what you are missing by your microscopic examination of sexual activity to the exclusion of aspects which are the fuel that ignites it. Intellectual, imaginative, romantic, emotional. This is what gives sex its surprising textures, its subtle transformations, its aphrodisiac elements. You are shrinking your world of sensations. You are withering it, starving it, draining its blood.

‘If you nourished your sexual life with all the excitements and adventures which love injects into sensuality, you would be the most potent man in the world. The source of sexual power is curiosity, passion. You are watching its little flame die of asphyxiation. Sex does not thrive on monotony. Without feeling, inventions, moods, no surprises in bed. Sex must be mixed with tears, laughter, words, promises, scenes, jealousy, envy, all the spices of fear, foreign travel, new faces, novels, stories, dreams, fantasies, music, dancing, opium, wine.

‘How much do you lose by this periscope at the tip of your sex, when you could enjoy a harem of distinct and never-repeated wonders? No two hairs alike, but you will not let us waste words on a description of hair; no two odors, but if we expand on this you cry Cut the poetry. No two skins with the same texture, and never the same light, temperature, shadows, never the same gesture; for a lover, when he is aroused by true love, can run the gamut of centuries of love lore. What a range, what changes of age, what variations of maturity and innocence, perversity and art …

‘We have sat around for hours and wondered how you look. If you have closed your senses upon silk, light, color, odor, character, temperament, you must be by now completely shriveled up. There are so many minor senses, all running like tributaries into the mainstream of sex, nourishing it. Only the united beat of sex and heart together can create ecstasy.’

POSTSCRIPT

At the time we were all writing erotica at a dollar a page, I realized that for centuries we had had only one model for this literary genre – the writing of men. I was already conscious of a difference between the masculine and feminine treatment of sexual experience. I knew that there was a great disparity between Henry Miller’s explicitness and my ambiguities – between his humorous, Rabelaisian view of sex and my poetic descriptions of sexual relationships in the unpublished portions of the diary. As I wrote in Volume III of the Diary, I had a feeling that Pandora’s box contained the mysteries of woman’s sensuality, so different from man’s and for which man’s language was inadequate.

Women, I thought, were more apt to fuse sex with emotion, with love, and to single out one man rather than be promiscuous. This became apparent to me as I wrote the novels and the Diary, and I saw it even more clearly when I began to teach. But although women’s attitude towards sex was quite distinct from that of men, we had not yet learned how to write about it.

Here in the erotica I was writing to entertain, under pressure from a client who wanted me to ‘leave out the poetry’, I believed that my style was derived from a reading of men’s works. For this reason I long felt that I had compromised my feminine self. I put the erotica aside. Rereading it these many years later, I see that my own voice was not completely suppressed. In numerous passages I was intuitively using a woman’s language, seeing sexual experience from a woman’s point of view. I finally decided to release the erotica for publication because it shows the beginning efforts of a woman in a world that had been the domain of men.

If the unexpurgated version of the Diary is ever published, this feminine point of view will be established more clearly. It will show that women (and I, in the Diary) have never separated sex from feeling, from love of the whole man.

Anaïs NinLos AngelesSeptember, 1976