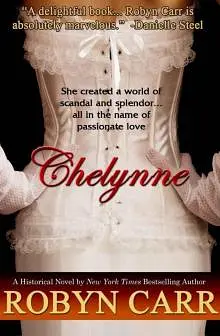

by Robyn Carr

“Why?”

“That is for the soul that has nothing left to believe in. Eternal life is only for the soul that in strength can endure living.”

“Chelynne, don’t ponder this so deeply. Think only about recovery now. Rest and eat.”

“I’m not much good at being a countess. In truth, I don’t much want to be.”

“That’s no fault of yours,” he said sternly. “From now it will be made easier for you.”

“I don’t like London much,” she told him.

“Then as soon as you can travel we’ll go to the country. Will that help?”

Not entirely, she thought. But she smiled and nodded her head.

“Chelynne, things will be better than they have been, I promise you. Just get well.”

How simple the matter of making a man cringe with guilt, she thought. She nodded and pretended that simple devotion. It kept him at bay better than anything else.

“I was called to Whitehall when you were ill, and begged off. I’m afraid I can’t avoid it any longer. Will you be all right if I leave you for a short time?”

Again the smile, the brief nod. She could see that he was most reluctant to leave her. She wondered then if there was some love for her after all. But she quickly put it out of her mind. He would feel obligated, of course, to help her during times of great crisis. He was not a man to take duty lightly. The one thing she had learned was that to be tolerated and endured was less dignified than being hated. And it was infinitely more painful.

He patted her hand, kissed her brow, and left her.

His Majesty King Charles had received a message early in the day from the earl of Bryant. It read that the countess was greatly improved and that he sought the earliest possible audience. Charles gave the messenger an appointment time for the afternoon. He breakfasted with the queen, dined with his mistress at noon, and played tennis in the early afternoon. He walked to his apartments with a trail of courtiers and banked by his friend George Villiers and his brother James, the duke of York.

“So, Bryant can leave the petticoats now, sire?” Buckingham asked.

“It seems Her Ladyship is on the mend,” the king replied.

“You’ve acquired an interest in her, haven’t you, sire?” James asked.

“You’ve acquired an interest in my interests,” was the reply.

“Will Bryant be going home or shall he become a guest of Your Majesty?” Buckingham asked.

“What is your wager, George?”

“There seems a full house at the Tower. I wager he goes home, sire.”

“Don’t put too much money on it,” Charles advised.

“There’s no proof he’s guilty of anything,” James put in. “So far as we can see.”

Charles was mute. He wasn’t saying any more.

“There’s no such thing as a guilt-free man,” George commented.

“And who would know that better than you, George?”

“Not a soul, sire,” he confessed.

“There are those who have the opinion you’ve not done your share of visiting in the Tower.” Charles stopped walking and waited for Buckingham to catch up. “What do you think of that?”

Buckingham bowed. “I think Your Majesty’s infinite wisdom and profound sense of justice have many times saved the innocent from unscrupulous slander and character assassination.” George smiled into Charles’s laughing eyes. The king started walking again.

“You know better, I warrant.”

“No one serves you more loyally, sire,” George defended himself.

“You serve no one better than yourself, George. It’s because I know that better than anyone that you’re wearing a head.”

“You’re most generous, sire.”

Charles stopped abruptly and stared at him. This friendship had weathered many a storm. It seemed they were always in the midst of an argument or just recovering from one. His eyes were serious and grave but there was a cynical smile on his lips. He started walking again without further comment.

“You’re suspicious of Bryant?” James asked.

“I’m suspicious of everyone,” Charles replied.

“I’m most curious about his story,” James ventured.

“Your curiosity will have to suffer. I see Bryant alone.”

The king went into his apartments and left the majority of his courtiers outside. While he was helped into his coat and wig, George and James stood a short distance away, murmuring with their heads together. Charles looked in their direction once or twice, understanding the mood of the conversation without hearing a word. How much influence did Bryant have with the king? What part did the countess play? The many possibilities would be carefully analyzed.

Charles knew they wouldn’t discover the real reason for his interest here since he was a long way from understanding it himself. Sir John had served the crown loyally and was a man Charles personally liked. Since his father’s lands had been sold, John would have to petition the king for permission to buy out Shayburn. Charles’s consent would leave one baron angry with the king’s favoritism. It occasionally created dissension at court. Had Bollering not guessed that Charles would approve of his appointment to his old family lands? Charles was not a man to easily forget a loyalty. And he was a man to appreciate being eased of constant petitions from his subjects. If they could settle this without upsetting the realm he would be satisfied.

And the countess of Bryant. Not very much time had passed since Minette’s death. His beloved sister. He had allowed her marriage to Philippe, whose constant abuse and mistreatment finally brought on her death. Another virtuous maid lost forever because of the limits of his protection. He knew there was little room for virtue at Whitehall.

Charles was not convinced that Chelynne was his own flesh. He never pondered things of that nature severely. He claimed many of the children of the women he bedded because it would be unchivalrous not to. The fact that she was lovely and sweet interested him more. If there was a way to prevent England and his court from destroying her he would see to it. If there was not, he would accept it.

As to Hawthorne, Charles did not forget his loyalty either. Neither did he forget a mistake, a betrayal, however minor.

When Bryant arrived Charles was glad to see the signs of fatigue and worry. He marked it as a positive sign.

“The countess is improved, I’m told.”

“She is, sire, and I thank you for your interest.”

“Thank me? That’s a new twist.”

“I thank you,” Chad said simply.

“You’ve not been out of your walls in a long time, Bryant. I believe you did sit vigil at her bedside.”

“You can be certain, sire. She was extremely ill.”

“And the cause?”

“We’re not certain, sire.”

“But I’ve a mighty good guess, since I made it my business. I made your comings and goings my business, too. I know that you didn’t leave your house.”

“I was being watched?”

“No. You were being heavily guarded. You were unaware?”

A flicker of surprise registered in Chad’s eyes. “Completely, Your Majesty.”

“The purpose was to see that you did not flee.” Charles watched him closely.

“What reason would have me flee, sire?”

“You had not heard?”

“I’ve been in touch with nothing, sire. I did in fact sit with my wife through her illness and came here at the first sign she would be safe with just her servants.”

“We have new guests in the Tower. A baron from your state, Shayburn, and most surprisingly, a man you’ve killed.”

Chad’s eyes widened considerably but he tried to keep his composure. “Arrested?”

“Indeed they were arrested. Lord Shayburn claims that Sir John Bollering has ravaged and destroyed that shire and murdered on his land. Bollering reports he did nothing and that Shayburn, in a fit of anger at being fairly bought out, set fire to anything immovable

in that town to keep from passing it along. What do you know of it?”

“Christ,” Chad muttered. “That’s ruined it, unless—”

“Unless what?”

“I must ask, sire, was the manor house burned?”

“That and village houses, warehouses, barns and carts. Just about everything there.” Chad marveled at Charles’s ability to remain calm. He seemed not upset at all. But he knew that this tolerance could be a temporary thing. He began a long story of what he and John and a brace of men had done in Bratonshire. Charles listened carefully.

“That old feud was due to Shayburn’s treachery. We’ve been aware for a long time that he mismanaged that land and was guilty of more than a dozen severe crimes. Unfortunately there was no way to prove him guilty, for he kept false records and dealt in secrets. We finally came across a document that would incriminate him, but if it was burned in the house it is useless to us now.”

“What do you speak of?”

“Contracts for money given to finance Dutch vessels. The treason would have been a tired charge, years old, but the character is the same in the man. Everything he has attained came through thievery of one sort or another. He aided both sides equally in the wars, securing his one high card in every circumstance.”

“A rather expensive habit,” Charles drawled.

“The people of Bratonshire have supported that habit for years, sire. I placed my father’s old manservant in that house and Sebastian was able to locate the contract with the Dutch. I assume Shayburn held it with the purpose of using it in the future if necessary.”

“And that is only one of the affairs in your sorry state. Creditors, I’m told, are lining up at your door.”

“Not quite so bad as that, Your Majesty. I’ve dealt largely in credit to keep my money available for emergencies, such as aiding John Bollering in buying back his lands.”

“I don’t think I have to ask, but that farce of a duel? Why would that be necessary?”

“John was seen on the baron’s lands and they set out in numbers to have him murdered. There would have been no trial, you can be assured.”

“And those people who were murdered? Abused?”

“None were by Bollering hands. They were taken safely away and the damage was a farce. Those killed by Shayburn were real.”

“Your dealings seem to have been all a farce, my lord, aggravating Shayburn’s wrath no small bit.”

“I have no proof beyond my word, sire, but Shayburn has been guilty of thievery and murder since before Lord Bollering originally lost his land to him. We have in our household now a lass who was raped and beaten and used for the amusement of that animal for debts of a minimal amount belonging to her father. There are a dozen more stories there, each more gruesome than the next. I would have sought to remove him even without Sir John’s aid.”

“And you couldn’t have done it more reasonably than you have?”

Chad had a great many things he wished to tell his king, to excuse or at least explain the action he had taken. But he was without evidence. “No, sire. I could not.”

Charles took in an exasperated breath. “The price of power,” he muttered.

“Sire, you are not well acquainted with Lord Shayburn. At least not as I am. I accuse him, but without proof. John Bollering is not only rightful heir to that land but loyal to the crown and a just lord. We thought to buy Shayburn out just as he did John’s father. It is not any more just by law, but by a man’s moral code, it is fair.”

“And will you stand on this principle before me? Before my ministers? Before the whole of England?”

Chad looked Charles in the eyes, unfaltering. “If it is my only recourse, to my death.”

Charles relaxed. “I hadn’t thought death in demand here; there’s been enough of that. It is true, however, that in defiling my land and my people you defile the crown, and that is treason, however virtuous the cause. It would better suit my mood to see the three of you bend your backs to the chore of putting all you have destroyed right.”

Chad smiled. “Should you gift us with the absence of one overfed baron, you would see Sir John and me do ten times the labor there, and happily.”

“Had you attempted to settle with Shayburn?”

“Quite generously, sire. He refused my offer of twice the land in Virginia and gold to support him. He would have England or nothing.”

“I am faced with a choice between evils and that does not please me. I will reserve judgment while supporting my guests in the Tower. Do you think you would like to join them?”

“You have no need to fear that I would flee your decision, sire. I am caught and prepared to abide by your rule.”

“A trifle late,” Charles muttered. “I had not worried that you would run. I think you’ve quite exhausted yourself of that.”

“Yes, sire. I’ve quite exhausted myself of that.”

During this brief exchange the two looked at each other. Charles felt a certain kinship with Chad since the days of exile. Both were fleeing something then that they hoped to have restored. Chad’s coming home was a lot later than Charles’s. Charles remembered this man as a youth, his loyal and determined support of his king. If he had ever met an honest man it was Chadwick Hawthorne. But Charles was cautious. He thought it best to keep his subjects from knowing how much credence he gave their word.

“And I am weary of slaughter and useless fighting. I would see the matter done. I will give you my decision in a few days.”

“Thank you, sire. I am at your service.”

“I would like to visit the countess. With your permission.”

“Of course, sire. She is still weak. Perhaps it would be best to give her a few more days.”

“It is my intention to offer her a position as Lady to the Queen’s Bedchamber and apartments at Whitehall. I know more of her condition than you might guess.”

Chad’s eyes darkened. “If I have been negligent in her care, I am deeply repentant, sire.”

“Repentance will not cure her,” Charles replied.

Chad spoke low, softly. “I hadn’t intended that as a cure.”

“I am not one to lecture on the treatment of women. I have failed in that enough to lose my credibility. If she suffers unduly in your home, she is welcome to another abode and the pension will come from your own purse. Her decision will be final and there will be no interference from you. Is that understood?”

“I will not interfere, Your Majesty.”

“I will tell you this once more, Bryant. The action you have taken does not please me. In conspiring against one of my barons you as much as conspire against me, whether or not you think of it in those terms. Now there is waste where there once was life. I cannot see use in more of the same and this feud must end here. Your grace lies in the fact that little of this unsavory business is known and I am impatient to be finished with it. If you get anything good out of this, it is not what you have duly earned but is thrown on you in a generous fit.”

“Thank you, sire.” Chad bowed, and left his king and Whitehall.

Moments had passed when York entered and found Charles in his closet playing with his medicines and whistling. Neither spoke. Buckingham followed, joining them.

“Bryant goes home to the countess,” Buckingham declared.

“Correct,” Charles confirmed. “Did you win your wager?”

“I did.”

James scowled, the loser. He had thought his brother much more angry with this business. “I don’t suppose I’ll learn the reason for losing one hundred pound,” James sulked.

“I don’t suppose,” Charles laughed.

“Would Your Grace like to wager on which lordly guest leaves the Tower first?” Buckingham offered.

“Shayburn,” James returned. “For two hundred pound. Gold.”

Charles looked to Buckingham and saw his nod. He went back to stirring the posset, amused.

“When must he make his debt good, sire?” George inquired.

&nb

sp; “He’s safe, as I see it. They’ll likely leave together.”

“And what of the charge?”

“What charge?”

“Treason, at the very least,” York insisted.

“That’s a bit harsh, James. Don’t you think?”

“I think it’s generous,” York argued.

“Well, perhaps it is best that you are you and I am I. I am much more generous. Which one of you will send for Bollering for me?”

“Bollering will get it, then?”

“I think he will accept lordship there. My mood is so improved I think raising him to baron too modest.”

“Your temper cools quickly,” Buckingham observed. He remembered the hard glint to Charles’s eyes when he heard the full score of accusations on both sides of that feud.

“Temper? I was not angry, George. This is what I have wanted all along.”

CHAPTER EIGHTEEN

As the illness faded for the countess of Bryant so did spring make its presence felt upon the land. Brown yielded to the promise of green and the rains were soft and sweet.

Chad looked in on his young wife frequently, and though he did not usually find her in a conversational mood, he was amazed with the speed of her recovery. He took note that her health became progressively better as small tokens of cheer arrived from the king. The fear vanished that her sickness would touch her beauty just as a violent storm marks the land. She emerged from her misfortune more radiant than he would have believed possible.

Chelynne’s manner had greatly changed since her close encounter with death. She seemed to have a new hold on herself, a new determination. She was hardly scampering about, as her condition was still weak, but she was carefully groomed every morning and her silky skin was touched with the rose flush he remembered. He marveled at the slim and seductive curve of her red lips and was still enticed with the fine, mysterious arch of her brows. But in the eyes there was the memory of trials. When he would inquire after her well-being and look into her eyes he did not see that warm adoration that had been there the summer before. Now there was a determined distance. She had not seen even seventeen summers and her eyes held the wisdom and pain of one hundred years. They held him at bay with the merest stare. She was ever as demure, but her gaze only a pace away from daring him to touch her. Chad, with his wealth of worldly knowledge, was completely at odds as to how to win her again.