The gate was broken. She remembered how many people had come through it each week to visit her father and mother. The front steps were rotting. She picked her way cautiously. She looked through the window. The house was vacant, dust on the floors, cobwebs in the windows.

Someone had said you could never go home again. She hadn’t understood until this moment. This broken-down shell wasn’t her home. The people who had made it a place of warmth and love and safety were gone.

Eunice wished she hadn’t come. Leaning her forehead against the glass, she closed her eyes, feeling a sense of loss so deep she felt she was drowning in it. Turning away, she went down the steps and closed the gate behind her. She walked along Colton Avenue, looking at the houses where friends had once lived. Tullys, O’Malleys, Fritzpatricks, Danvers. Where were they now? Where had they all gone when the mines closed?

The street came to a dead end. She walked back on the other side and got into her rental car. She sat for a long time, her mind numb with disappointment and confusion. Where now? She turned the key, made a U-turn, and headed up to the main street. Turning right, she headed for the south end of town and then turned left and drove up the hill.

Paul turned the wedding photo his mother had given him face-down on the passenger seat. He wasn’t going to think about what his mother had said. Not now. Not when he was so tired he couldn’t think straight. He found the on-ramp to I-5.

Bone-weary and groggy, he turned on the radio. He needed something to get his mind off depressing matters and worries about the future. Patsy Cline was belting out “Your Cheatin’ Heart.” He punched the Select button and heard Carly Simon singing, “You’re so vain, I’ll bet you think this song is about you, don’t you—” Swearing, he tried again and heard the first strains of a song he’d once told Eunice reminded him of her: Jim Croce’s “Time in a Bottle.” He punched the Off button.

He felt sick to his stomach.

The steep Grapevine was ahead of him, winding down from the mountains, the Central Valley stretching out like a patchwork quilt in front of him. Trucks moved at a snail’s pace in the far right lane, gears tortured, brakes at the ready. He stopped at the foot of the mountains for gas and a cup of coffee to go. At this rate, he’d be back in Centerville by ten. He’d have time to swing by the house, change his clothes, and be in the church office by noon. He could straighten it up, put it to rights before anyone came in. Nobody would even know he’d been gone. And if anyone did ask about Eunice, he’d just say she was visiting Tim again.

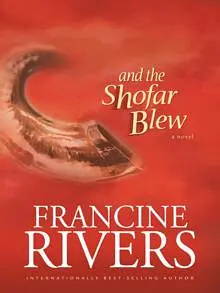

Was it only because of his Scripture reading that morning that Samuel could not stop thinking about the ram’s horn? The only place the shofar was still used was in Jewish ceremonies, and even many Jews didn’t understand. All men were accountable for their sin, and the penalty was still death. The shofar sounded to announce the coming of the Lord. When it sounded, the people were to assemble, confess, and repent. When it sounded, the people were to worship. The shofar announced the Day of Atonement and Jubilee. It sounded in the midst of battle.

A call to gather God’s people, a call to repentance, a call to enter into battle. God’s voice came to the multitude through the prophets in the days of old, but now the Lord spoke to each believer through the Holy Spirit.

Oh, Lord, I know I am in battle. How long must I fight this war? I’m weary of it. Heartsick. Despairing. Only You can save him, and yet he turns away and turns away and turns away. How do You bear it? What kind of power love did it take for You to hang on that cross and listen to them mock You when You were making a way for them to have redemption and eternal life? What keeps You from wiping the world clean by fire?

He bowed his head, wishing he could give up his soul as Jesus had done, and enter his rest. But God was the one who counted his days. God gave him breath for a reason. Samuel had been at war for years now—one voice weeping before the Lord, pleading for the softening of a single human heart that grew harder with each year that passed.

Eunice hadn’t been back to this cemetery since her mother passed away. She parked the car and entered beneath the rusted iron arch. The first funeral she’d attended here was for a boy she knew who drowned in the river when he was eight. The last funeral was for her mother, two years after her father had been carried up the hill by six pallbearers. She and her mother had planted forget-me-nots around the grave after her father’s service, and Eunice had planted more of them when she returned to bury her mother. Then she put the house up for sale.

When she found their resting place and knelt, she plucked weeds and smoothed the grass as though it were a blanket over them. She missed her father and mother even more now. Alone and far away from a place she should have been able to consider home, away from a man she had pledged to love until death parted them, she longed for connection to those who’d love her unconditionally.

Oh, God. Oh, Abba, I want to come home. Couldn’t You take me now? Let this grief stop my heart from beating.

Wishful thinking. God had already counted her days and was not likely to take her life just because living was so painful. Jesus knew better than anyone the pain of life on this earth. Jesus knew what it felt like to be betrayed.

Weary, she stretched herself out upon the graves, arms spread wide as though to embrace them both. The earth was cold beneath her.

Oh, her parents were the fortunate ones. They no longer had to suffer disappointment. And they would have suffered with her if they’d lived long enough to know Paul was not a man of his word. She longed for their wisdom. She ached at the loss, knowing she could’ve told them anything and everything and it wouldn’t have changed their opinion or their love for her or Paul. They would’ve wept with her and advised her. But would she have listened?

She knew already what her father would’ve said, and her mother would have agreed. Forgive. No matter what Paul’s done, you’re still his wife. No matter what she had seen when she walked into the church office, her responsibility was unchanged. Jesus was Lord. What had He seen as He looked down from the cross but a crowd gathered to mock Him? Yet He died for them.

Her mother and father would have told her to forgive, but what about going back to Paul? Would they have told her to go on living with a man who excused his sin and continued to walk in the ways of his father rather than obey God?

God said to do what was right.

Oh, God, what is right in this situation?

Paul wondered how many times Eunice had driven this route to see Timothy. How many times had she stopped somewhere and had a meal alone because he’d been too busy to go south with her?

He didn’t want to think about that now. He had to consider sermon ideas. Every one that came to him made him uncomfortable. He could always pull out notes from a past sermon, make a few changes, and go with that. Was there a holiday approaching? some civic activity that needed a boost?

When the freeway branched, he took Highway 99 north. He reached for his coffee. He took his eyes off the road for only a couple of seconds, but when he looked up again, a jackrabbit was running across the road in front of him.

Samuel remembered the evening three elders came together in the old church and decided not to close the doors.

We gave it one last try, Lord. Were we wrong? Oh, Father, it’s as though I stood on the shores of the Jordan and saw the Promised Land. And I’m still looking at it, from the valley of death this time, hoping and praying I’ll see the day when Paul leaves the wilderness of sin behind him and crosses over into the realm of faith.

Eunice. Sweet Eunice. Don’t let her slip away from us. Lord, help her. Protect her heart, for from it has come springs of living water. Keep her on the Rock, Lord. Keep her in the palms of Your scarred hands.

“Daddy.” Eunice sobbed. “Daddy.” What do I do?

“Miss?”

A man stood nearby, holding a shovel. Startled, Eunice clambered up, dashing the tears from her eyes. He was a few years older than she, dressed in soiled jeans and a checked wool shirt, his boots clumped with earth. A

grave digger? The groundskeeper? He looked concerned.

“Can I help you, miss?”

Embarrassed, she brushed the grass from her blouse and slacks. “I was just . . . ” Just what? Confiding her problems to her dead parents? She looked at his shovel uneasily. She didn’t know who this man was or if he was a threat.

He set the shovel aside. “Would you like to talk about it?” His face was so kind, his eyes so gentle.

“My husband . . . ” Her throat closed. Her mouth worked. She looked away. The man sat on the grass as though he had all the time in the world. She felt calm in his presence. He seemed so ordinary, just a man taking a break from whatever work he had been doing. She told him everything.

“I don’t know whether to go back. He’s a pastor, you see.”

The man said nothing.

She looked into his eyes. “It’s not just about his infidelity to me.”

“No, it isn’t.”

She ran her hand over the grass that covered her parents’ graves. “My father was a pastor, too. He worked at being a good one.”

“What advice would your father give you?”

“Forgive.” She smiled wryly through her tears. “It would be so much easier if my husband were repentant.” Her smile died.

“Were those at the cross repentant?”

She bowed her head, aching at the thought of what Jesus must have felt. What she was suffering now was merely a drop of the sorrow Jesus had drunk on the day of His crucifixion.

“Let the Lord’s strength sustain you, Eunice.”

“I know that in my head. But my heart . . . even if Paul were repentant, I don’t know if I could ever really trust him again. And if I can’t trust him, what sort of wife would I be? It could never be the way it was.”

“Are you looking for a way out?”

“Maybe. Out of the pain, at least.”

He smiled tenderly. “There’s no getting around that. It comes with life in this world, and following the One you do.”

“I don’t know what kind of future we can have together after what he’s done.”

“One day’s trouble is enough. Face tomorrow when it comes.”

“I’d like to run away from it all and never look back.”

“You’ll carry it with you everywhere you go.”

She knew that already. She’d come all the way across the country and escaped none of the anguish. “So what’s your advice?”

His eyes filled with compassion. “Trust in the Lord. Do what’s right. And rest.” He rose, took his shovel, and walked away.

Rest, she thought. In Him. I need to be still and stop running. I can’t trust my husband or mother-in-law or friends, but I can trust God. And I can believe that the Lord is working, even now. I can trust that Christ will turn all this pain to His good purpose.

Someday.

In the meantime, she needed to find a place to eat and then a place to sleep.

Alone in the courtyard, Samuel continued to plead before the throne of heaven. How long, O Lord, how long must I bear this sorrow? I have known and done Your will for over seventy years, but I know men, too, and it will take the blasting of a shofar to make Paul stop and listen. Lord, please. Make him aware of the pain he’s caused. Bring him to account for it. Turn him, Lord, turn him so profoundly, there will be no turning back for him. So profoundly that the change in him will bring light to others.

Paul cried in pain as hot coffee splashed over his right leg. Jamming on the brakes, he gripped the wheel with both hands and turned sharply to avoid running over the jackrabbit in the road ahead of him. Horns blasted. He heard a loud screech, felt the car swing into a hard circle. Terrified, he tried to compensate and screamed as a semi barely missed plowing into his door.

The sound of the horn was in back of him, in front, bearing down on him long and loud. He was going to die! He was going to die!

I don’t understand, Lord, Samuel prayed. How could I have been so wrong about a man? I thought I was doing Your will in calling Paul Hudson to Centerville Christian. But I have watched him go in like a wolf among Your sheep, leading them astray, filling them with false teaching and groundless hope. Or is he the lost lamb? Oh, God, I don’t know anymore. How I wish Your voice was as loud as that ancient shofar so that I could hear and know what You want me to do.

You know.

Tears rolled down his cheeks.

Paul skidded off the road. Enveloped in a cloud of dust, he came to a dead stop, heart pounding so hard he thought he’d pass out. Still gripping the wheel, he shook, adrenaline roaring in his veins. He got his breath back, shoved the gearshift into Park, and put his head against the steering wheel.

Someone tapped on the window. “Mister! You okay?”

No, he wasn’t. He was anything but okay. He raised his hand and nodded without looking at the stranger.

“Do you need a tow truck?”

How many others had been hurt in his attempt to miss hitting a jackrabbit?

He pressed a button and lowered the window enough to ask if anyone was hurt.

The man looked back. “No one that I can see. But cars are stacking up. My truck’s blocking one lane. I’d better get rolling. Are you sure you’re okay? I can call in for help.”

“Yeah, I’m okay.”

“Man, someone’s watching out for you. That’s all I can say. Another split second and I would’ve hit you head-on with my semi. What made you swerve like that?”

“Instinct, I guess. Something ran across the road.”

The trucker said a couple of choice words and ran back to his vehicle. He jumped up, slammed the door. The truck roared to life, ground into gear. The air horn blasted. The truck was so close Paul felt he was being melted by the noise. The driver brought the truck around and back onto the high-way, heading north. A dozen cars followed, all slowing as each driver took a good long look at Paul.

He was too shaken to get back on the road yet. So he sat, waiting for his heart to slow down. He saw his wedding picture shattered on the floor below the passenger seat. Eunice gazed up at him—adoring, trusting—through broken glass. And it hit him then like a blow in his stomach what he had done to her, what he had done to their marriage.

Oh, God . . .

He’d almost killed himself in the effort to miss a jackrabbit running across the road, but he’d been running over Eunice for years.

Every word Paul’s mother had said sank in and took hold, shaking the foundations of his lifework. I’ve lost her. I’ve lost Euny.

All his life, Paul had wanted to be like his father. And now he had succeeded, realizing much too late that his earthly father was not a man to be emulated. He had become like his father, all right—cheating on his wife, cheating on his Lord and Savior, Jesus Christ. He’d become good at using the church to fan his pride and build his own empire. He’d served the same idols his father had: ambition and arrogance. Oh, he’d made sacrifices—plenty of them. His dreams, his integrity, his restraint, his moral fiber and character. Those he should’ve been protecting, he’d abandoned—faithful friends like Samuel and Abby Mason, Stephen Decker, and a dozen others before he cast away his own son and wife. Or had he cast them off first?

They’d all tried to reach him. They’d all tried to warn him. But he’d been too full of pride, too full of himself to listen. Oh, he knew what he was doing, he thought. He was building a church, wasn’t he? He was working for the Lord, wasn’t he? And that justified everything, didn’t it?

Oh, God, oh, Jesus . . .

How dare he even utter the name?

When Paul arrived home, there were fifteen messages on his answering machine. He prayed as he listened to each, but there wasn’t a call from Eunice. All had to do with church business, including a reminder that he didn’t have to worry about Sunday. He had scheduled a well-known ecumenical speaker. Well, that was a relief, anyway.

The last message was from Sheila. “I think Reka is the one who told Eunice to come to the office.” She called h

er a foul name. “If you don’t fire her, you’re an idiot. I’m sorry about what I said to you in the office. I think you can understand I was upset. I do love you, but I think we both know it’s over. I’m calling from Palm Springs. Rob is going to fly here on the way home from Florida. I haven’t told him anything. I have no intention of telling him. I just thought this was a good idea for damage control. If any rumors arise, they’ll die quick enough when I come home with a nice tan and my hubby on my arm. You just have to deal with Eunice—”

He punched the Delete button. Deal with Eunice. Isn’t that what he’d been doing for the last ten years? He looked at the notes, schedules, and programs on his desk, a dozen neatly laid out. He picked up the class schedule and read down the list: Power Praying: How to Get God to Answer; Embracing the Imposter Within: Making Friends with Your Past; Improving Your Self-Image; Alternate Lifestyles: A Course in Loving Your Neighbor; Yoga: Exercise to Inspire Meditation. One of the deacons’ wives was holding a party on finding peace in the midst of storms through aromatherapy. He felt the hair stand up on the back of his neck. Sheila wasn’t the problem. She was just the most recent in a long line of sins he’d been committing over the years. The mountainous weight of them pressed down on him until he could hardly breathe.

How do I get out from under this? How do I get back on the road? Oh, Jesus, help me! How did I ever get so far off track in the first place?

Who do you say that I am?

Paul held his head and wept. He’d been behaving worse than an unbeliever.