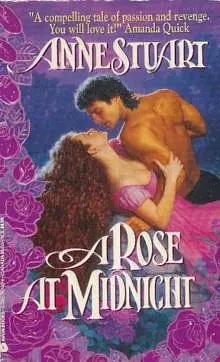

by Anne Stuart

Chapter 10

She was a most surprising female, Nicholas thought, a day and a night later, as his decrepit carriage continued its journey. No matter what he did to her, no matter what hardships she had to endure, she neither complained nor begged, bargained nor pleaded. They’d been traveling since the previous morning, when he’d plucked her from that damned tangle of passengers in the overturned mail coach. When he’d seen the mountainous creature who’d landed on top of her, he’d had very real doubts about her chances of survival. But she’d emerged, furious, unscathed, not even her formidable temper and determination squashed.

They’d stopped a number of times, to change horses, to eat, to relieve their bodies, and each time he’d kept her hands tied, allowing her only the briefest illusion of privacy. She’d sat huddled in the corner, knocked around by the ramshackle carriage, and she’d never said a word of complaint. He knew for a fact how uncomfortable she must be—every bone in his own body ached, and his muscles felt as if they’d been pulled in every direction. She had to be feeling worse, without even the dubious cushion of her hands to brace herself every time they hit a particularly onerous pothole.

But she’d said nothing, except to cast an occasional glare in his direction. She’d slept fitfully through the long night, the jostling of the carriage knocking her into wakefulness, and when he’d helped her down the next morning she’d almost collapsed in his arms.

But she’d managed to right herself almost immediately, swaying slightly in her determination, and he had to admire her. Not enough to unfasten one of his best neckcloths from around those dangerous wrists of hers, but enough to charge Tavvy to make more stops than he would have considered strictly necessary.

It was dark once more, and from the tension around her mouth, the paleness of her skin, he thought she’d probably inured herself to the notion of spending another night on the road. She wouldn’t know that they’d crossed the border into Scotland hours ago, and that they weren’t far from his hunting lodge. Not far from a fire, and a bed, and an end to this incessantly rocking carriage.

He had no intention of telling her either. To tell her would be to give her hope, give her more reason to keep fighting, and she already had too much fight in her. He’d done what he could to demoralize her, but she’d refused to be cowed. Once they reached the hunting lodge he’d finish the job, thoroughly, efficiently, but part of him was loath to do so. He didn’t really want to see her shattered, abased. He wasn’t sure why not. It couldn’t be any tender emotion such as pity or mercy. He didn’t possess either.

Actually, he couldn’t even imagine her humbled. But he knew that was nonsense on his part. There wasn’t a man alive he couldn’t break, if he put his mind to it, and a woman, even one as fierce and determined as Ghislaine de Lorgny, would be child’s play. As soon as he rid himself of any lingering, foolish scruples.

He’d take her to bed, of course. She’d probably fight like a wildcat—she did every time he touched her. But she also purred. He’d seen that look in the back of her magnificent dark brown eyes, half-aroused, half-startled, and he knew he could take her. And knew in the end that the fight would leave her, panting and breathless in his arms.

He liked the idea, liked it very much. He hadn’t been so interested in a woman, so interested in anything, even the fall of the cards, in longer than he cared to remember. His murderous little Ghislaine was arousing his temper, his interest, his body, in a truly memorable fashion. He almost regretted that he was going to turn her into one more forgettable female.

Almost was the operative word. For thirteen years she’d haunted him; her fate, his guilt. With one ill-advised act of revenge she’d manage to wipe out his guilt. Once he finished with her, she’d be gone from his consciousness, for the first time in those long years. He wondered if he’d miss her.

It was about twenty-five years since he’d ventured to Scotland—not since he was a young boy, still possessed of dreams for the future. He’d kept away since then—there was no room in his life for country sojourns or fishing trips. But during the endless, uncomfortable trip north he found he was looking forward to being in Scotland again, even in such an unpredictable season as spring. Rustication was good for anyone—his Uncle Teasdale used to swear by it at regular intervals. Maybe he’d settle in, take his time with the rebellious Ghislaine, not return to the city until autumn. He used to like the country around his father’s seat in the Lake District. The glory of the apple blossoms, the taste of fresh cream and honey, the green of the hills, and the clear blue of the lakes. He’d fish this time—didn’t people come to Scotland to fish? He hadn’t indulged in the sport since his last trip there, but he could still remember the thrill of catching a five-pound salmon. And how good that salmon had tasted, cooked over an open fire, just him and old Ben, the hostler who’d been his bodyguard, his keeper, his boon companion until a fever had carried him off.

“How are you at cooking salmon? Have you ever cooked it before?” he asked abruptly.

She lifted her head, surprise lighting the darkness in her eyes. “Of course. I can cook anything.” It wasn’t a boast—she was too weary and miserable to boast. It was a simple statement of fact.

“I’ll catch a salmon for us in the morning,” he said. “If you promise not to poison it. It would be too great a crime, to poison a Scots salmon.”

“The morning?” she echoed wearily.

The carriage was slowing in the twilight, and Nicholas glanced out the window at the familiar countryside. He could see the hunting lodge up ahead, and even in the shadows he could see that it hadn’t fared well in the intervening years. Part of the roof had caved in, and he had little doubt that various forms of wildlife had taken up residence in the derelict old building. He only hoped that they were edible forms. Tavvy was an excellent trapper, and he was famished.

“In case you hadn’t noticed, ma belle,” he murmured, “we’re here. The journey is over.”

He expected some sign of enthusiasm. He got none, only increased wariness. Probably with some justification, he admitted to himself. She had to know that his plans for her were not of the noble sort.

“What next?” she asked, her voice flat and emotionless, and he wondered what had happened to her during those lost years, when she said she’d been in a convent. What had taught her to bury her feelings, her reactions, to face the world with blind, accepting eyes.

“Next?” he echoed. “Next, ma mie, you cook dinner for me. Something sumptuous—I’m absolutely starving.”

“What about your cook?”

“Peer out the window at our destination, Ghislaine. You will find that my hunting lodge doesn’t come equipped with an intact roof, much less a retinue of servants. If we’re to eat tonight, you’re going to have to concoct something. I think I’d probably even prefer poison to Tavvy’s culinary attempts. At least your food doesn’t taste as if it would kill you, even if it’s more immediately effective.”

She did look out the window at the derelict building as Taverner pulled the hired horses to a weary halt, but if she felt dismay she managed to hide it. As she managed to hide most things. “And how am I supposed to come up with dinner?” she asked sharply, and he knew with sudden relief that she’d actually do it.

“We have a few basics with us. Sugar, flour, coffee, and brandy. Tavvy can probably forage something fresh. I’m counting on you to do the rest—you French are endlessly resourceful.”

“Aren’t we, though?” she replied, eyeing his throat with a fondness that he knew signified dangerous intentions.

He didn’t wait for Tavvy, leaping down from the carriage with an exhausted sigh. The air was damp and cold—he could see the icy vapor of his breath in front of him, and he realized absently that he’d been chilled for the last few hours. He hadn’t even noticed.

He turned to Ghislaine. She stood in the doorway of the carriage, her hands still bound in front of her, and she looked past him at the tumbled-down building. “Just what I would have exp

ected you to live in,” she said sharply.

He’d hoped she’d stumble when she climbed down, but she didn’t. He knew he could put his hands on her anyway—there was no one to stop him except himself. But he wanted to wait. To savor the anticipation.

The lodge had belonged to his father, the last remnant of a squandered inheritance. None of the Blackthornes had been particularly fond of Scotland, with Nicholas being the sole exception, and for a moment he felt real grief at the state of the beloved old building. And then he banished it. Tavvy could make it habitable—Tavvy could make any squalid hole habitable.

The inside of the lodge was even worse than the exterior had led him to expect. The main hall was roofless—filled with debris from the forest surrounding them, and he could see that a fire had been partially responsible for its swift decay. The back of the building was in better shape, with two rooms untouched by the fire, though there was no guarantee what condition the huge fireplace would be in. One room had been used for storage, the other was a bedroom. Tavvy and Ghislaine stood on either side of him, surveying the disarray.

“Looks like we’ve got our work cut out for us,” Nicholas announced briskly. “First things first. Tavvy, you find us something to eat. Rabbit, quail, anything that’ll fill our empty bellies. There’s a farm just over the next rise—you might be able to find some eggs, milk, even butter. There’s no telling what Ghislaine could do with such wonders.”

“I’m gone,” Tavvy said with a nod. “Once I unload the coach. You’ll be wanting your things in this room?”

“It looks the most promising,” Nicholas said, glancing around him at the sagging bed frame, the littered fireplace.

“And Mamzelle’s?”

Nicholas gave him a bland smile. “In here as well.”

If his reply disturbed Ghislaine she refused to show it. “If you’d untie my hands,” she said evenly, “I’ll see what I can find of the kitchens.”

“The kitchens were on the west side of the house, and they’ve caved in completely. You’ll have to make do with this fireplace. Assuming it’s not stuffed with birds’ nests or the like.”

“Very well,” she said, holding out her wrists with utmost patience.

Tavvy had already quit the room, leaving the two of them there in the murky light. “Now why do I think untying you might be a very dangerous thing to do?” he mused, making no move to release her.

“I can’t be your servant with my hands bound,” she said, tension creeping into her voice.

“But you can’t stab me in the back either,” he pointed out.

She growled, low in her throat. “Very well,” she said, dropping her arms against her long skirts.

He caught them, glad of the excuse to touch her, glad of the excuse to feel her jerk nervously at the feel of his hands on her, knowing it wasn’t as simple as fear or hatred. “I suppose it would be a waste of time to ask you for your word of honor.”

“It depends on what you ask.”

“That you not try to murder me tonight? A small request, surely. Even a bloodthirsty creature like yourself must long for dinner and a decent night’s sleep.”

“Am I going to be allowed a decent night’s sleep?” she asked, glancing pointedly at the single bed.

“Of course,” he said, not hesitating. She would sleep, all right. He would tire her out so much she would sleep for days.

She didn’t believe him, of course, but she nodded. “Very well, then. I give you my word.”

He was still holding her bound wrists. Her hands were like ice against his, but they remained motionless in his grip. “Why should I believe you?” he said, not wanting to release her.

“Because, unlike you, I have a sense of honor. If I give my word, I do not break it.”

He believed her. Most women of his acquaintance had scant appreciation for honor or truthfulness, but he already knew that Ghislaine had little in common with the dashing widows and muslin company he spent his time with. Even at fifteen, she’d been something quite out of the ordinary. He should have guessed she’d turn out to be astonishing.

He unfastened the rumpled neckcloth, tucking it in his pocket for further use. “See what you can find for us to eat,” he said, “and I’ll start a fire.”

Her expression was frankly disbelieving. She turned from him, and he had to admire her unconscious grace, hampered as she was by his cousin Ellen’s oversized clothes. She would probably be a great deal more graceful without them, he thought for a brief, dreamy moment. He had every intention of finding out. He’d put off that particular pleasure for too long as it was, and the wench at the last inn hadn’t sated his appetite, merely increased it.

In the meantime, he needed to concentrate on getting some warmth in the room. If he was going to divest Ghislaine de Lorgny of her clothes, and he planned to do just that, he wanted it to be warm enough for her to enjoy it. And for him to enjoy her.

The heat of the fire managed to penetrate to the center of the large room, but not much beyond that. It had astonished Ghislaine that a dissolute wastrel like Nicholas Blackthorne could accomplish something as profoundly practical as starting a fire, but accomplish it he had, including removing the old bird’s nest that had clogged the chimney and sent billows of smoke out into the room. He’d also dragged the bed closer to the center of the room, disturbing a nest of field mice from the aging mattress. There were no linens, but he’d brought in the lap robes from the carriage and spread them across the ticking. He’d used all the lap robes, she noticed, leaving only one bed equipped. And she wondered again who was going to sleep where. Surely he didn’t intend the three of them to bundle together on that sagging mattress. Though it might be the warmest, safest alternative. Or perhaps not, she thought belatedly, remembering things she’d been told by the more experienced women she’d met in Paris.

It had taken all her considerable self-control not to bolt when he’d left her alone in the room, surrounded by the most depressing assortment of foodstuffs. But she’d given her word, and even if he didn’t expect honor from her, she expected it from herself. Even more so now that she knew how devoid he was of that particular trait.

Blackthorne had even managed to unearth a broom from some part of the ruined house, but when he took to stirring the dust up into swirling clouds that settled in the food she was trying to assemble, she took it from him with wifely hands and banished him to sit by the fire. The act gave her a belated feeling of despair. How easy it was to give in, to fall into pleasant ways, forgetting her determination, forgetting his villainy.

Taverner was better than she would have thought, returning with butter, eggs, thick cream, and a slab of sharp aged cheese. While the two men busied themselves in the other room she managed wonders—a sweet custard spiced with a few withered apples from last fall’s harvest, a hearty peasant omelet with potatoes and the last of an aging slab of bacon, and coffee, wonderful coffee. If it were up to her she would have coffee with every meal. It had become the one pure pleasures left to her, and she savored the scent and flavor of it as it brewed over her makeshift cooking fire.

The table had only three working legs—she’d had to prop it against a wall. She filled the plates evenly, filled the mugs with coffee, and sat down, waiting.

She didn’t expect praise, and she didn’t receive it. Nicholas threw himself down in a chair that was far too decrepit to make such behavior wise, reached over, and took her plate, exchanging it with his. “You have no objections, I assume?” he asked with false politeness.

“None at all,” she murmured.

Taverner watched this byplay from his shifty eyes. “Maybe you’d better take mine,” he said, reaching across the table and exchanging plates with his master. “She’s a downy one, the Mamzelle is.”

“If you like, I’ll eat everyone’s dinner,” Ghislaine offered with false sweetness. “I’m famished, and the food is getting cold while you two argue. Choose your plate and let me eat in peace.”

Nicholas leaned back in t

he chair. “Now there’s a challenge if ever I’ve heard one. Can’t let the girl think we’re cowards, Tavvy. We’ve at least a one in three chance of surviving. Unless she’s decided to put a period to all three of us at once, like some damned Shakespeare tragedy.”

“Trust me,” she said, “I’m no longer willing to die in order for you to meet your just reward.”

He and Tavvy had been depleting the bottle of brandy in the back room, and now he took it and tipped a generous amount into Ghislaine’s mug of coffee. “No martyr, is that it? Just as well. Martyrdom is unbelievably tiresome.”

“I gather you speak from experience,” she said.

“Only from having to suffer from exposure to them. Saints are very tedious, my pet. I much prefer sinners.”

“I imagine you do.” The omelet was delicious, even though she mourned the absence of any herbs. It was just as well, though. Blackthorne would have probably decided thyme was an arcane form of arsenic, and consigned her lovely omelet to the fire.

Once he decided to risk it he ate well, more than she’d seen him eat in their days together. There was an odd light to his eyes, one that made her uneasy. As if he’d been biding his time since he’d taken her away from Ainsley Hall, but now that time of waiting was over. She didn’t now whether she was frightened or relieved.

His next words proved her right. “I’ll want you to go into town, Tavvy,” he said casually, leaning back with his own mug of brandy. He’d finished the coffee, following it with straight liquor, and he looked calm, relaxed, and very dangerous. “There was an inn we passed not more than five miles away where you can bespeak a room. See if they’ve any word from London. I imagine Jason Hargrove is well on his way to good health, otherwise we would have heard. See if you can find some laborers to do something about the roof. Perhaps you might see if there are any young ladies closer in size to Mamzelle. She must be tired of dressing in a giant’s clothes.”

“Ellen’s not a giant,” she said indignantly, attack in this unexpected quarter slicing through her defenses.