“Did you get it?” Dougless whispered.

“Oh, yes. My parents thought I was crazy and said an Elizabethan miniature was no possession for a child, but when they saw me, week after week, giving all my allowance toward the purchase of that miniature, they began to help me. Then, just before we left England, when I’d begun to feel that I was never going to get enough money together to buy it, my father drove me to the antique shop and presented the portrait to me.”

The man sat back in his seat, as though that were the end of the story.

“Do you have the portrait?” Dougless whispered.

“Always. I’m never without it. Would you like to see it?”

Dougless could only nod.

From his inside coat pocket, he withdrew a little leather case and handed it to her. Slowly, Dougless opened the box. There, on black velvet, was the portrait Nicholas had had painted of her. It was encased in silver and around the edges were seed pearls.

Without asking permission, Dougless lifted the miniature from the case, turned it over, then held it up to the light.

“My soul will find yours,” Reed said. “That’s what it says on the back, and it’s signed with a C. I’ve always wondered what the words meant and what the C stood for.”

“Colin,” Dougless said before she thought.

“How did you know?”

“Know what?”

“Colin is my middle name. Reed Colin Stanford.”

She looked at him then, really looked at him. He glanced down at the portrait, then up at her, and when he did so, he looked at her through his lashes, just as Nicholas used to do. “What do you do for a living?” she whispered.

“I’m an architect.”

She drew in her breath. “Have you ever been married?”

“You do get to the point, don’t you? No, I’ve never been married, but I’ll tell you the truth: I once left a woman practically at the altar. It was the worst thing I’ve ever done in my life.”

“What was her name?” Dougless’s voice was lower than a whisper.

“Leticia.”

It was at that point that the stewardess stopped by their seats. “We have roast beef or chicken Kiev for dinner tonight. Which would you like?”

Reed turned to Dougless. “Will you have dinner with me?”

My soul will find yours, Nicholas had written. Souls, not bodies, but souls. “Yes, I’ll have dinner with you.”

He smiled at her and it was Nicholas’s smile.

Thank You, God, she thought. Thank You.

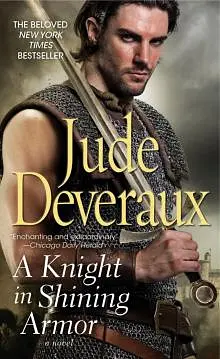

THE WRITING OF A KNIGHT IN

SHINING ARMOR

JUDE DEVERAUX

In the fourteen years since I wrote A Knight in Shining Armor, I’ve received many queries about the book, especially about how I came to write it. Many times I’ve been told that it is “a perfect love story,” but I think that the appeal of the book for me—and, yes, it’s my favorite of my books—and for readers is the underlying theme.

What people don’t know is that A Knight in Shining Armor is about alcoholism.

Before I start a book, I think, I want to write about . . . I fill in the blank with something that’s of interest to me, then build the plot on that subject. Sometime during the 1980s I was researching another book when I came across some information that startled me. I read that, in many cases, alcoholism is as much a state of mind as it is a physical problem. I had assumed that a person who had stopped drinking, would no longer be an alcoholic.

But what I was reading—and forgive my paraphrasing, as I’m not an expert on this—said that there was such a thing as an “alcoholic personality.” In fact, a person didn’t even have to drink to have this personality, and in that case, he was called a “dry drunk.”

What interested me about this personality was that a person who had it desperately needed to break the spirit of another human being. A “dry drunk” will choose the strongest, most moral, and most generous person he or she can find, then dedicate his life to trying to control, and therefore change, this person. The ultimate goal is to be able to say, “I’m not so bad. Sure, I do bad things, but look at this person. Everyone thinks she (or he) is so good, but I’ve just proven that she, too, can be bad.”

An example of this thinking at work is depicted in the movie Dangerous Liaisons. The characters played by Glenn Close and John Malkovich search for the strongest, most highly moral person they can find, portrayed by Michele Pfeiffer, then set out to destroy her.

After I spent some time reading about the alcoholic personality, I knew I wanted to write about it. I also wanted a heroine who was strong but believed herself to be weak, who was generous, the kind who’d help another human even if it caused her hardship, yet thought her generous spirit was a weakness.

I wrote down my goal, then set about creating a story that would show what I wanted. However, I knew my heroine had to be in a nondrinking relationship, because I was sure that if she were involved with an active alcoholic, I’d lose the sympathy of the reader. Unfortunately, there are a lot of people—including many therapists—who say, “All you have to do is leave,” and they truly believe leaving a bad relationship is that easy. Also, I didn’t want to give away the problem in one sentence. All I’d have to do is have the heroine’s boyfriend drink his fourth whiskey and everyone would know they were reading about an alcoholic relationship. No, I wanted more subtlety than that. In fact, at the time, I told my editor that I wanted to write a book about alcoholism but that I was never going to mention the word in the book.

As some of you know, I often write about a family named Montgomery. The Montgomerys are all brilliant, rich, and afraid of nothing. They are true heroes. I thought, What if someone was born into that family but felt she didn’t fit in? What if she was intimidated by her glorious relatives and felt that she’d never live up to their standards?

From these questions, I created Dougless Montgomery, a young woman who had three formidably perfect older sisters and had, all her life, felt inferior to them.

It was easy to imagine Dougless being swept away by a man with an alcoholic personality. Robert Whitley was a successful man, and on the surface, he seemed like someone Dougless could show to her family with pride. If Dougless herself couldn’t be the tower of accomplishment her siblings were, then she’d do the next best thing and bring such a person into her family.

Once I had my idea of Dougless’s background, I needed a story that would change her. First of all, I needed to get her away from the family that made her feel inferior. But how to do that? Part of the Montgomery creed is that they always help each other. How could I put my heroine in a situation dire enough to fundamentally change her personality yet prevent her relatives from bailing her out?

It was this idea of taking my heroine “away” that made me think of writing a time travel novel. I’d always loved to read time travel stories, so I thought it would be interesting to write one. Right away, I saw that I needed two things from my plot. First, my heroine needed to discover that her generosity and kindness were worthy traits. And, second, Dougless needed to accomplish something that made her truly proud of herself, and this accomplishment had to be so big that she could overlook her past failures, her bad boyfriends, and all the embarrassing situations she’d been in.

From these two needs, I constructed a basic time travel plot in which a medieval man comes forward in time and Dougless helps him. She’d be reluctant at first, but her sweet nature wouldn’t allow her to abandon him. In order for Dougless to learn that she was actually a very strong woman who could rely on herself, I decided to send her back to the Elizabethan era, where she’d have to use all her wits just to stay alive. And since I didn’t want her disappearing under the protective arm of a man, I had her return to a time when the Elizabethan man didn’t remember her.

After I had my plot, I spent months researching. When I had read time travel novels in the past, I had always been bored by the long explanations of political history. What I wanted to read about, a

nd certainly to write about, was what the people wore, what they ate. I wanted to know how they thought. I wanted to know every detail of Elizabethan life—with no boring politics!

I enjoyed the research very much, and as I discovered things that fascinated me, I added to my plot so I could include what I’d learned. For example, I’d never thought about what people did with their children before there were day-care centers. While the serfs were out working all day, who took care of the toddlers that were too young to work but old enough to wander into trouble? I can tell you that I was shocked to read that the children were bound tightly enough to put them into a stupor, then hung from a peg in the wall!

When I had many pages of plot and hundreds of Rolodex cards full of research, I went to my cabin in the Pecos Wilderness in New Mexico and isolated myself for three and a half months while I wrote the book. I got up at daybreak, ate a bowl of cereal, then wrote by hand until noon. After lunch I went for a walk and plotted the next day’s scenes in my head. Since my cabin was at a nine-thousand-foot altitude, this meant climbing above the tree line, often to eleven and twelve thousand feet. That summer I climbed so much that when I got into bed at night, my calves were so heavy with muscle that my heels didn’t touch the sheet.

When the book was finished, I’d poured so much of my heart into it that, instead of mailing it, I flew to New York to personally deliver the manuscript to Pocket Books.

I was pleased with the book for several reasons. For one thing, I felt I’d done what I’d set out to do: I’d written about alcoholism without ever mentioning the word. And I’d made my heroine realize that she was strong enough to stand up to her controlling boyfriend—and to her overbearing sister. On the day I wrote the scene where Dougless tells her sister not to speak to her in a disrespectful manner, I did a dance of triumph.

In the years since A Knight in Shining Armor was first published, I’m happy to say, readers have seemed to like the book as much as I loved writing it. However, in the last few years, I’ve thought that I’d like to go back through the book and apply some of what I’ve learned over time about writing. So, in January of 2001, that’s what I did. I didn’t change the plot, didn’t really add any new information, but I somehow managed to add fifty pages to the book. In the end, I think it’s now a smoother read, and, maybe, it’s a bit more understandable why Dougless wanted to marry a jerk like Robert.

I thank all of you for your kind words about a book that has been so close to my heart for so many years, and I hope you continue to enjoy the book for a long time to come.

Turn the page for a preview of

Jude Deveraux’s newest novel,

Stranger in the Moonlight

From Pocket Books

PROLOGUE

EDILEAN, VIRGINIA

1993

In all of her eight years, Kim had never been so bored. She didn’t even know such boredom could exist. Her mother told her to go outside into the big garden around the old house, Edilean Manor, and play, but what was she to do by herself?

Two weeks ago her father had taken her brother off to some faraway state to go fishing. “Male bonding,” her mother called it, then said she was not going to stay in their big house alone for four whole weeks. That night Kim had been awakened by the sound of her parents arguing. They didn’t usually fight—not that she knew about—and the word “divorce” came to her mind. She was terrified of being without her parents.

But the next morning they were kissing and everything seemed to be fine. Her father kept talking about making up being the best, but her mother shushed him.

It was that afternoon that her mother told her that while her father and brother were away they were going to stay in an apartment at Edilean Manor. Kim didn’t like that because she hated the old house. It was too big and it echoed with every footstep. Besides, every time she visited the place there was less furniture, and the emptiness made it seem even creepier.

Her father said that Mr. Bertrand, the old man who lived in the house, had sold the family furniture rather than get a job to support himself. “He’d sell the house if Miss Edi would let him.”

Miss Edi was Mr. Bertrand’s sister. She was even older than he was and even though she didn’t live there, she owned the house. Kim had heard people say that she disliked her brother so much that she refused to live in Edilean.

Kim couldn’t imagine hating Edilean since every person she knew in the world lived there. Her dad was an Aldredge, from one of the seven families that founded the town. Kim knew that was something to be proud of. All she thought was that she was glad she wasn’t from the family that had to live in big, scary Edilean Manor.

So now she and her mother had been living in the apartment for two whole weeks and she was horribly bored. She wanted to go back to her own house and her own room. When they were packing to go, her mother said, “We’re just going away for a little while and it’s just around the corner, so you don’t need to take that.” “That” was pretty much anything Kim owned, like books, toys, her dolls, her many art kits. Her mother seemed to consider it all as “not necessary.”

But at the end, Kim had grabbed the bicycle she’d received for her birthday and clamped her hands around the grips. She looked at her mother with her jaw set.

Her dad laughed. “Ellen,” he said to his wife, “I’ve seen that look on your face a thousand times and I can assure you that your daughter will not back down. I know from experience that you can yell, threaten, sweet talk, plead, beg, cry, but she won’t give in.”

Her mother’s eyes were narrowed as she looked at her laughing husband.

He quit smiling. “Reede, how about you and I go . . . ?”

“Go where, Dad?” Reede asked. At seventeen, he was overwhelmed with importance at being allowed to go away with his dad. No women. Just the two of them.

“Wherever we can find to go,” his dad mumbled.

Kim got to take her bike to Edilean Manor and for three days she rode it nonstop, but now she wanted to do something else. Her cousin Sara came over one day but all she wanted to do was explore the ratty old house. Sara loved old buildings!

Mr. Bertrand had pulled a copy of Alice in Wonderland out of a pile of books on the floor. Her mom said he’d sold the bookcase to Colonial Williamsburg. “Original eighteenth century and it had been in the family for over two hundred years,” she’d muttered. “What a shame. Poor Miss Edi.”

Kim spent days reading about Alice and her journey down the rabbit hole. She’d loved the book so much that she told her mother she wanted blonde hair and a blue dress with a white apron. Her mother said that if her father ever again went off for four weeks her next child just might be blonde. Mr. Bertrand said he’d like a hookah and to sit on a mushroom all day and say wise things.

The two adults had started laughing—they seemed to find each other very funny. In disgust Kim went outside to sit in the fork of her favorite old pear tree and read more about Alice. She reread her favorite passages again, then her mother called her in for what Mr. Bertrand called “afternoon tea.” He was an odd old man, very soft-looking, and her father said that Mr. Bertrand could hatch an egg on the couch. “He never gets up.”

Kim had seen that few of the men in town liked Mr. Bertrand, but all the women seemed to adore him. On some days as many as six women would show up with bottles of wine and casseroles and cakes, and they’d all laugh hilariously. When they saw Kim they’d say, “I should have brought—” They’d name their children. But then another woman would say how good it was to have some peace and quiet for a few hours.

The next time the women came they’d again “forget” to bring their children.

As Kim stood outside and heard the women howling with laughter, she didn’t think they sounded very peaceful or quiet.

It was after she and her mother had been there for two long weeks that early one morning her mother seemed very excited about something, but Kim wasn’t sure what it was. Something had happened during the night, some adult t

hing. All Kim was concerned with was that she couldn’t find the copy of Alice in Wonderland that Mr. Bertrand had lent her. She had one book and now it was gone. She asked her mother what happened to it as she knew she’d left it on the coffee table.

“Last night I took it to—” The sentence wasn’t finished because the old phone on the wall rang and her mother ran to answer it, then immediately started laughing.

Disgusted, Kim went outside. It seemed that her life was getting worse.

She kicked at rocks, frowned at the empty flower beds, and headed toward her tree. She planned to climb up it, sit on her branch, and figure out what to do for the long, boring weeks until her dad came home and life could start again.

When she got close to her tree, what she saw stopped her dead in her tracks. There was a boy, younger than her brother but older than she was. He was wearing a clean shirt with a collar and dark trousers; he looked like he was about to go to Sunday School. Worse was that he was sitting in her tree reading her book.

He had dark hair that fell forward and he was so engrossed in her book that he didn’t even look up when Kim kicked at a clod of dirt.

Who was he? she thought. And what right did he think he had to be in her tree?

She didn’t know who or what, but she did know that she wanted this stranger to go away.

She picked up a clod and threw it at him as hard as she could. She was aiming for the top of his head, but hit his shoulder. The lump crumbled into dirt and fell down onto her book.

He looked up at her, a bit startled at first, but then his face settled down and he stared at her in silence. He was a pretty boy, she thought. Not like her cousin Tristan, but this boy looked like a doll she’d seen in a catalogue, with pink skin and very dark eyes.

“That’s my book,” she yelled at him. “And it’s my tree. You have no right to them.” She grabbed another clod and threw it at him. It would have hit him in the face but he moved sideways and it missed.