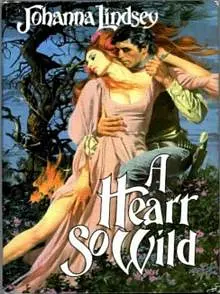

A Heart So Wild

Johanna Lindsey

When Courtney Harte learns that her father is still alive, she asks Chandos, a top gunman, to escourt her through Indian territory to him.

Courtney Harte is certain her missing father is a alive, lost somewhere deep in Indian territory. But she needs a guide to lead her safely through this dangerous, unfamiliar country, someone as wild and unpredictable as the land itself. And that man is the gunslinger they call Chandos.

Courtney fears this enigmatic loner whose dark secrets torture his soul, yet whose eyes, bluer than the frontier sky, enflame the innocent, determined lady with wanton desires. But on the treacherous path they have chosen they have no one to trust but each other--as shared perils to their lives and hearts unleash turbulent, unbridled, passions that only love can tame.

Chapter 1

Kansas, 1868

ELROY Brower slammed down his mug of beer in annoyance. The commotion across the saloon was distracting him from the luscious blonde sitting on his lap, and it was seldom Elroy got his hands on as tempting a creature as Big Sal. It was damned frustrating to keep getting interrupted.

Big Sal wiggled her hefty buttocks against Elroy’s crotch, leaning forward to whisper in his ear. Her words, quite explicit, got the results she’d expected. She could feel his tool swelling.

“Whyn’t you come on upstairs, honey, where we can be alone?” Big Sal suggested, voice purring.

Elroy grinned, visions of the hours ahead exciting him. He intended to keep Big Sal all to himself tonight. The whore he sometimes visited in Rockley, the town nearest his farmstead, was old and skinny. Big Sal on the other hand, was a real handful. Elroy had already offered up a little prayer of thanks for having found her on this trip to Wichita.

The rancher’s voice, raised in anger, caught Elroy’s attention once more. He couldn’t help but listen, not after what he’d seen just two days ago.

The rancher told everyone who would listen that his name was Bill Chapman. He’d come into the saloon a short time earlier and ordered drinks for one and all, which wasn’t as generous as it sounded because there were only seven people there, and two of them were the saloon girls. Chapman had a ranch a little ways north and was looking for men who were as fed up as he was with the Indians who were terrorizing the area. What had caught Elroy’s attention was the word “Indians.”

Elroy had had no Indian trouble himself, not yet anyways. But he’d only come to Kansas two years ago. His small homestead was vulnerable, and he knew it—damn vulnerable. It was a mile from his nearest neighbor, and two miles from the town of Rockley. And there was only Elroy himself and young Peter, a hired man who helped with the harvest. Elroy’s wife had died six months after they arrived in Kansas.

Elroy didn’t like feeling vulnerable, not at all. A huge man, six feet four and barrellike, he was used to his size getting him through life without problems, except for the ones he started himself. No one wanted a taste of Elroy’s meaty fists. At thirty-two, he was in excellent condition.

Now, though, Elroy found himself worried about the savages who roamed the plains, intent on driving out the decent, God-fearing folk who’d come to settle there.

They had no sense of fair play those savages.

no respect for even odds. Oh, the stories Elroy had heard were enough to give even him the quivers. And to think he had been warned he was settling damn close to what was designated Indian Territory—that huge area of barrenness between Kansas and Texas. His farm was, in fact, just thirty-five miles from the Kansas border. But it was good land, damn it, right between the Arkansas and Walnut rivers. What with the war over, Elroy had thought the army would keep the Indians confined to the lands allotted them.

Not so. The soldiers couldn’t be everywhere. And the Indians had declared their own war on the settlers as soon as the Civil War broke out. The Civil War was over, but the Indians’ war was just getting hot. They were more determined than ever not to give up the land they thought of as theirs.

Fear made Elroy listen carefully to Bill Chapman that night, despite his longing to retire upstairs with Big Sal.

Just two days ago, before he and Peter had come to Wichita, Elroy spotted a small band of Indians crossing the west corner of his land. It was the first group of hostiles he had ever seen, for there was no comparing this band of warriors with the tame Indians he’d seen on his travels West.

This particular group numbered eight, well armed and buckskinned, and they’d been moving south. Elroy was concerned enough to follow them, from a distance, of course, and he trailed them to their camp on the fork of the Arkansas and Ninnescah rivers. Ten tepees were erected along the east bank of the Arkansas, and at least another dozen savages, women and children included, had set up home there.

It was enough to turn Elroy’s blood cold, knowing this band of either Kiowa or Comanche were camped only a few hours hard ride from his home. He warned his neighbors of the Indians camped so close by, knowing the news would throw them into a panic.

When he arrived in Wichita, Elroy told his tale around town. He’d scared some people, and now Bill Chapman was stirring up interest among the regulars in the saloon. Three men declared they’d ride with Chapman and the six cowhands he’d brought with him. One of the regulars said he knew of two drifters in town who might be inclined to kill a few Injuns, and he left the saloon to go in search of them, see if they were game.

With three enthusiastic volunteers in hand and the chance of two more, Bill Chapman turned his blue eyes on Elroy, who had been listening quietly all this time.

“And what about you, friend?” the tall, narrow-framed rancher demanded. “Are you with us?”

Elroy pushed Big Sal off his lap but kept hold of her arm as he approached Chapman. “Shouldn’t you be letting the army chase after Indians?” he asked cautiously.

The rancher laughed derisively. “So the army can slap their hands and escort them back to Indian Territory? That don’t see justice done. The only way to insure a thieving Indian don’t steal from you again is to kill him so he can’t. This bunch of Kiowas slaughtered more’n fifteen of my herd and made off with a dozen prime horses just last week. They’ve cut into my pocket too many times over these last years. It’s the last raid I’m standing for.” He eyed Elroy keenly. “You with us?”

Cold dread edged down Elroy’s spine. Fifteen head of cattle slaughtered! He had his only two oxen with him, but his other livestock on the farm could have been stolen or butchered in just the one day he’d been away. Without his livestock, he was wiped out. If those Kiowas paid him a visit, he was through.

Elroy fixed his hazel eyes firmly on Bill Chapman. “I saw eight warriors two days ago. I followed them. They’ve got a camp set up by a fork in the Arkansas River, about thirteen miles from my farm. That’s about twenty-seven from here if you follow the river.”

“Gawddamn, whyn’t you say so!” Chapman cried. He looked thoughtful. “They might be the ones we’re after. Yeah, they could’ve made it that far this soon. Them bastards can travel farther faster than any critter I know of. Were they Kiowas?”

Elroy shrugged. “They all look the same to me. But those braves weren’t trailing any horses,” he admitted. “There was a herd of horses at their camp, though. About forty.”

“You gonna show me and my cowhands where they’re camped?” asked Chapman.

Elroy frowned. “I got oxen with me to carry a plow back to my farm. I don’t have a horse. I’d only slow you down.”

“I’ll rent you a horse,” Chapman offered.

“But my plow—”

“I’ll pay to store it while we’re gone. You can come back for it, can’t you?”

“W

hen are you leaving?”

“First thing in the mornin”. If we ride like hell and if they’ve stayed put, we can reach their camp by mid-afternoon.“

Elroy looked at Big Sal and grinned a huge grin. As long as Chapman wasn’t fixing to leave now, Elroy wasn’t giving up his night with Big Sal, nossir. But tomorrow…

“Count me in,” he told the rancher. “And my hired hand, too.”

Chapter 2

FOURTEEN hell-bent men rode out of Wichita the next morning. Young Peter, nineteen, was thoroughly excited. Nothing like this had ever happened to him before. He was thrilled for this chance. And he wasn’t the only one, for some of the men simply enjoyed killing, and this was a perfect excuse.

Elroy didn’t care much for any of these men. They weren’t his kind of people. But all of them had been out West much longer than he had, which made him feel inferior. They all had one thing in common, at any rate. Each had his own reason for hating Indians.

Chapman’s three regular hands gave their first names only—Tad, Carl, and Cincinnati. The three gunmen Chapman had hired were Leroy Curly, Dare Trask, and Wade Smith. One of the Wichita men was a traveling dentist with the unlikely name of Smiley. Elroy didn’t understand why so many folks who came West felt the need to change their names, sometimes to suit their occupations, sometimes not. There was the ex-deputy between jobs who had wandered down to Wichita six months ago and was still between jobs. How did he support himself, Elroy wondered, but he knew better than to ask. The third Wichita man was a homesteader like Elroy who’d just happened into the saloon last night. The two drifters were brothers on their way to Texas, Little Joe Cottle and Big Joe.

With hard riding and the hope of picking up a few more men, Chapman led the men into Rockley by noon that day. But the detour gained them only one more man, Lars Handley’s son, John. They found there was no hurry, however, because Big Joe Cottle, who’d ridden ahead with an extra mount, met them in Rockley and reported that the Kiowas were still camped on the riverbank.

They reached the Indian campsite in mid-afternoon. Elroy had never in his life ridden so hard. His backside was killing him. The horses were done in, too. He would never have ridden a horse of his own like that.

The trees and lush vegetation growing along the river gave Elroy and the others ample cover. They moved in close and watched the camp, and the roar of the river drowned out the little sounds they made.

It was a peaceful setting. Stately tepees spread out beneath the huge trees. Children tended the horses, and the women were gathered in a group, talking. One lone old man was playing with a baby.

It was hard to imagine that these were bloodthirsty savages, Elroy thought, and that the children would grow up to kill and steal. Why, the women were known to be even worse than the men at torturing captives, or so he’d heard. There was only one warrior visible, but that didn’t mean anything. As Little Joe pointed out, there might be other warriors, all taking siestas the way Mexicans did.

“We should wait until tonight, when they’re all asleep and unsuspectin”,“ Tad suggested. ”Injuns don’t like to fight at night. Somethin‘ “bout their dyin’ and their spirits bein” unable to find the happy huntin‘ grounds. A little surprise wouldn’t hurt none.“

“Seems to me we got surprise on our side right now,” Smiley pointed out. “If those warriors are all napping anyway—”

“They might not even be around.”

“Who says? They could be makin” weapons in them tepees, or humpin‘ their women.“ Leroy Curly chuckled.

“That’d be a mighty lot of women, then. There’s only ten tepees, Curly.”

“You recognize any of your horses over there, Chapman?” Elroy asked.

“Can’t say as I do, but they’re herded too close to get a good look at ”em all.“

“Well, I know Kiowas when I see ”em.“

“Don’t think so, Tad,” Cincinnati disagreed. “I believe they’re Comanches.”

“How would you know?”

“Same way you think you know Kiowas,” Cincinnati replied. “I know Comanches when I see ”em.“

Carl ignored them both, for Tad and Cincinnati could never agree on anything. “What’s the difference? Injuns is Injuns, and this ain’t no reservation, so it’s sure as hell these aren’t tame.”

“I’m after the ones that raided,” Bill Chapman interjected.

“Sure you are, boss, but are you willin” to let this band go their merry way if they ain’t the ones?“

“They could be the ones next year,” Cincinnati pointed out as he inspected his gun.

“What the hell’s goin” on?“ Little Joe demanded. ”You mean we blistered our butts all day and now you’re thinkin‘ of turnin“ back without killin’ ”em? Bullshit!“

“Easy, little brother. I don’t reckon that’s what Chapman was thinkin” at all. Was it, Mr. Chapman?“

“Not likely,” the rancher said angrily. “Carl’s right. It don’t make much difference which band of savages we got here. We get rid of this band and others will think twice before they raid around here.”

“Then what are we waitin” for?“ Peter looked around eagerly.

“Just make sure you save the women for last.” Wade Smith spoke for the first time. “I’m gonna have some. For my trouble, see?”

“Now you’re talking.” Dare Trask chuckled. “And here I thought this was gonna be just another routine job.”

There was now a new element to the excitement running through the men as they moved back to collect their horses. Women! They hadn’t thought of that. Ten minutes later the crack of rifles broke into the silence. When the last shot was fired there were four Indians left alive, three women and one young girl that Wade Smith had found too pretty to pass up. All four of the women were raped many times, then killed.

At sundown, fourteen men rode away. The ex-deputy was the only one of their casualties.

As they removed his body from the scene, they felt that his death was a small enough sacrifice.

The camp was quiet after they left, all the screams born away on the wind. Only the roar of the river was heard. There was no one at the camp to mourn the dead Comanches, who were unrelated to the band of Kiowas who had raided Bill Chapman’s ranch. There was no one to mourn the young girl who had caught Wade Smith’s eye with her dark skin and blue eyes, eyes that gave away the trace of white blood somewhere in her background. None of her people heard her suffer before she died, for her mother had died before they finished raping the girl.

She had marked her tenth birthday that spring.

Chapter 3

“COURTNEY, you’re slouching again. Ladies don’t slouch. I swear, didn’t they teach you anything in those expensive girls’ schools?”

The chastised teenager glanced sideways at her new stepmother, started to say something, then changed her mind. What was the use? Sarah Whitcomb, now Sarah Harte, heard only what she wanted to hear and nothing else. Anyway, Sarah was no longer looking at Courtney, her interest now drawn by the farm just barely visible in the distance.

Courtney straightened her back anyway, felt the muscles around her neck scream in protest, and gritted her teeth. Why was she the only one to feel the lash of Sarah’s scolding tongue? Sometimes the older woman’s new personality amazed Courtney. Most times, though, Courtney just kept quiet, drawing into herself as she had learned to do to keep out the hurt. It was a rare thing these days when Courtney Harte drew on her old courage, only when she was overly tired and just didn’t care anymore.

She hadn’t always been a veritable mass of insecurities. She had been a precocious, outgoing child—friendly, mischievous. Her mother used to tease her, saying she had a bit of the devil in her. But her mother had died when Courtney was only six years old.

In the nine years since, Courtney had been sent off to one school after another, her father unable to cope with the demands of a child while he was so deeply in mourning. But apparently Edward Harte had liked the arrangement, fo

r Courtney was allowed to come home only for a few weeks each summer. Even then, Edward never found time to spend with his only child. During most of the war years, he hadn’t been at home at all.

At fifteen, Courtney had suffered being unwanted and unloved too long. She was no longer open and friendly. She had become a very private and cautious young girl, so sensitive to the way others treated her that she would withdraw at the slightest hint of disapproval. Her many strict teachers were responsible for some of the girl’s awkward shyness, but most of it came from trying continually to regain her father’s love.

Edward Harte was a doctor whose thriving practice in Chicago had kept him so busy he rarely found time for anything but his patients. He was a tall, graceful Southerner who had settled in Chicago after his marriage. Courtney thought there was no man handsomer or more dedicated than he. She worshiped her father and died a little every time he looked at her with those vacant eyes, the same honeyed brown as her own.

He had found no time for Courtney before the Civil War, and it was even worse after. The war had done something terrible to this man who ended up fighting against the home he’d come from because of his humanitarian beliefs. After he came home in “65, he had not resumed his practice. He became reclusive, locking himself away in his study, drinking to forget all the deaths he’d been unable to prevent. The Harte wealth had suffered.

If not for the letter from Edward’s old mentor Amos asking Edward to take over his practice in Waco, Texas, Courtney’s father would probably have drunk himself to death. Disillusioned Southerners were pouring into the West, looking for new lives, Amos wrote, and Edward decided to become one of those who chose hope over disillusionment.

This was going to be a new life for Courtney, too. There would be no more schools, no more living away from her father. She would have a chance now to make him see that she wasn’t a burden, and that she loved him. It was going to be just the two of them, she told herself.

But when their train was delayed in Missouri, her father had gone and done the inconceivable. He had married their housekeeper of the last five years, Sarah Whitcomb. There had, it seemed, been some mention of the impropriety of a thirty-year-old woman traveling with Harte.