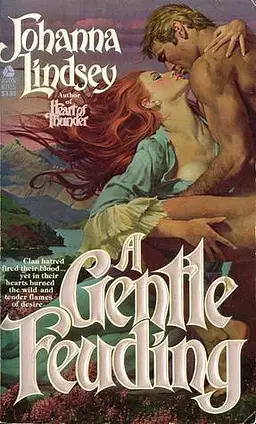

A Gentle Feuding

Johanna Lindsey

Chapter 1

Early May 1541, Aberdeenshire, Scotland.

A BRIGHT moon broke through fleeting clouds, lighting the Highland moors and casting five men into dark shadows. Five men waiting behind a steep crag far above the great Dee river. The river was a silver thread winding its way through the wide valley between the Cairngorm mountains and towering Lochnagar.

A burn turbulent with melted winter snow passed below, joining the Dee. This thick stream traversed Glen More, where MacKinnion crofts dotted what little fertile land there was.

All was quiet in the crofts. All was quiet in the glen. The five men heard only the melodic sound of water far below and their own ragged breathing. They crouched behind the crag, cold and wet from their river crossing.

They were waiting for the moon to reach its zenith, when it would cast no shadow. Then the tallest of them would set them on their task‑‑a task conceived out of bitterness. His clansmen were as nervous as he was.

“The moon is high, Sir William.”

William stiffened. “So it is,” he said, and began to pass out the green‑gold‑and‑gray‑striped plaids he had ordered made for that night. “Let it be done then, and done right. The cry will be the Clan Fergusson cry, no’ our own. And dinna kill all, or there’ll be no one left to say whose cry they heard.”

The five men moved away from their hiding place and gathered their horses. Swords were drawn and torches lit. And in a moment, a bloodcurdling war cry split the still night. Seven crofts were in their pathway, but the assailants expected to attack only three, for MacKinnion crofters were skilled warriors as well as farmers, and the few attackers had only surprise on their side.

The family in the first croft were barely awake before their small but was put to the torch. Their home was quickly consumed. Their livestock was butchered, but the crofter and his family were saved the sword. There was no blessing in that, for imprisoned in their inferno, their deaths were more agonizing.

A newly married couple lived in the second hut, the wife fifteen years old. She woke to the war cry with terror, terror that doubled when she saw her husband’s anguished face. He forced her to hide beneath their box bed, and then he went out to meet the attack. She never knew what happened to him. Smoke gathered in the thatched hut, suffocating her. It was too late to wish she had not defied her brother and married her beloved. It was too late for anything.

The third croft faired a little better, though not by much. It was a larger farm. Old Ian lived there with his three grown sons, a daughter‑in‑law and grandson, and a servant. Fortunately, Ian was a bad sleeper and was awake to see the newlyweds’ croft set on fire. He called his three sons to arms and sent his grandson to warn their closest neighbors. Simon was then to go to their laird.

The attackers met resistance at Ian’s croft, four strong fighters. Ian could still wield a mean cudgel, and he held out for precious time. One of Ian’s sons was dead, another wounded, and old Ian struck down before anyone heard the war cry of the MacKinnions. At that sound, the attackers fled.

It was an angry young laird who viewed the devastating scene in those dark hours before dawn. James MacKinnion halted his huge steed just as his cousin and friend Black Gawain ran into the newlyweds’ hut, a small cottage built only months before to welcome the bride. Only the low stone walls and a little of the roof remained of a home so lately filled with laughter and teasing.

For Black Gawain’s sake, Jamie hoped the but would be empty, but it was a slim hope and he knew it. He stared at the body of the young crofter, lying just outside the blackened door, the head half severed.

These clansmen of his, on the borders of his land, looked to Jamie for protection. It was beside the point that his castle was far away, up in the hills, and he could not have reached these people in time. Whoever had done this simply did not fear The MacKinnion’s wrath. Well, they would! By God, they would!

Black Gawain stumbled out of the blackened debris, choking from the smoke. He threw Jamie a look of relief, but Jamie was not convinced.

“Are you sure, Black Gawain?” he asked solemnly.

“She’s no’ there.”

“But are you sure, Gawain?” Jamie persisted. “I’ll no’ be wasting time searching the hills. The lass would surely have come forward ‘afore now if—”

“Curse you, Jamie!” Gawain exploded, but the hard look in his laird’s eyes made him call to his own men and give the anguished order to search the hut, thoroughly this time, leaving no board unturned.

Three men went inside. All too soon they returned, carrying the body of a young girl.

“She was under the bed,” a fellow offered lamely. Gawain took his sister and laid her gently on the ground, leaning over her.

Jamie tightened his grip on his reins. “At least she’s no’ burned, Gawain,” he offered quietly, there being nothing else he could offer. “She suffered little pain.”

Black Gawain did not look up. “No’ burned, but dead nonetheless,” he sobbed. “God, she shouldna have been here! I told her no’ to marry that bastard. She shouldna have been here!”

There was nothing Jamie could say, nothing he could do. Except make those who had caused this horror pay for it.

Jamie rode on with the dozen men he had brought with him from Castle Kinnion. They saw what had happened to the first croft. The third croft in the line of damage was untouched, but two of its men were dead, old Ian and his youngest son. Many animals lay slaughtered, including two fine horses Jamie himself had given Ian.

He felt his anger becoming an open wound. This was no common raid, but unpardonable slaughter. Who could have done such terrible damage? There were survivors. He would have a description, some clue at least.

If Jamie had guessed countless names, the name given him would have been his last guess.

“Fergusson. Clan Fergusson, and nae mistake,” Hugh said bitterly. “There were nigh a dozen of those cursed Lowlanders.”

“You saw old Dugald himself?” Jamie asked tightly, his eyes flaming.

Hugh shook his head, but he did not waver. “The clan cry was clear. The plaid colors were clear. I’ve fought enough Fergussons to know their colors as well as my own.”

“But you havena for two years, Hugh.”

“Aye, two years wasted,” Hugh spat. “Two years I could’ve been killing Fergussons sae I’d no’ be mourning a father and a brother now.”

Jamie said carefully, “It makes no sense, man. There’s many plaids resembling the Fergussons’, our own included. I must have more than a war cry anyone could imitate and colors seen in the dark.”

“It’s doubt yer have, Sir Jamie, and none here are blaming yer.” A crofter, one who had been warned by Simon, spoke up. “ ‘Twas a cry I thought never to hear again after these two years of peace, but hear it I did as the cowards fled down the burn.”

“I’ve been up the burn and seen the damage,” another man stated. “ ‘Tis what yer aiming to do about it we’re waiting to hear, Sir Jamie.”

Jamie was shocked by this challenge. Most of the men present were older. If his being only twenty‑five wasn’t bad enough, his boyishly handsome face made him seem even younger. Those close to him knew of his fierce temper and frequently harsh judgments, but these men had seen little of him in the two years since his father had died and he’d become laird of Clan MacKinnion. There had been no opportunity for them to fight alongside Jamie.

“You want me to lead you in revenge? I’ll do that gladly, for whoever strikes at you strikes at me.” Jamie returned their stares, boldly eyeing each man. None could mistake the cold resolve in his hazel eyes. “But I’ll no’ begin a long‑dead feud again without good reason. You’ll g

et your revenge, that I swear. But ‘twill be against those guilty and no other.”

“What more proof is needed?”

“A reason, man!” Jamie replied harshly. “I need a reason. You all fought Fergussons in my father’s time. You know they’re no’ a powerful clan. You know we outnumber them two to one, even when they’re joined with the MacAfees. Dugald Fergusson wanted an end to the feud. My own aunt insists the feud never should have begun, so I agreed to peace when there was no retaliation after our last raid two years ago. We’ve no’ raided them since, and they’ve no’ raided us. So can one of you give me a reason for what happened here tonight?”

“A reason? No, but here’s proof.” Ian’s oldest son stepped forward and threw a scrap of plaid at Jamie’s feet. The plaid was several shades of green and gold, with gray stripes.

At that moment a band of thirty men appeared, crofters and their sons who lived close to Castle Kinnion and had been gathered by Jamie’s brother.

“So be it,” Jamie said ominously, slowly grinding the unmistakable Fergusson plaid under his booted foot. “We ride south to Angusshire. No doubt they will be expecting us, but no’ so close on their heels as we will be. We ride now, to arrive at dawn.”

Chapter 2

JAMES MacKinnion moved slowly. An enveloping mist still clung to the dewy ground, and he was sopping wet from crossing the second of the two Esk rivers. He was tired from lack of sleep and the rough ride south. They had had to ride more than a mile out of their way to find a shallow river crossing. All things considered, he was in a foul mood. And he couldn’t squelch his disquiet. There was something wrong in all this, but he didn’t know what it could be.

He was alone, having left his men shrouded in the dawn mist by the river’s edge. Jamie and his brother and Black Gawain had separated in order to survey the area for signs of possible ambush. It was something he always did when a raid was expected, and this one surely was. And it was something he did himself, not as a display of courage, although, being alone, he risked being captured, but because the welfare of his clansmen was his responsibility alone. He would ask no man to do what he would not do himself.

The mist swirled and parted before him in a gentle breeze, revealing for a moment a wooded glen not far ahead. Then the mist settled again, and the vision was gone. Jamie rode for it; the trees were a pleasant change from the barren moors and heather‑clad hills.

He had never been this far east on Fergusson land before. He had never raided Lowlanders in the spring before, either. Autumn was the time for raiding, when rivers were broad but shallow, and cattle were fat from summer grazing and prime for market. He had always crossed the river in direct line with Tower Esk, the home of Dugald Fergusson. The swollen water had made that impossible this time. But their delays were short ones, and he was confident they were less than an hour behind the attackers, even though he and his men hadn’t found their trail. He would not give them time to celebrate their victory.

Jamie’s anger warred with his common sense. He wondered about the wisdom of his decision to ride south without further reflection. He had reacted to what facts he had. In truth, he could not have done differently. Dead men demanded he ride to avenge them. A scrap of plaid demanded he ride south. Yet . . . why? He would have given anything for more evidence. The act bordered on insanity. Was he sure of what he was doing?

Not knowing for sure ate away at him and turned him sour on the task ahead. Dugald Fergusson could not fail to know that Jamie had it within his power to wipe out his whole clan. The MacKinnions could do it alone, and they also had the alliance of two powerful northern clans, through the marriages of Jamie’s two sisters.

More than five hundred men could be raised if needed. Old Dugald must have known that. He had known of the first alliance three years before, and of the second just after Jamie’s father died and Jamie made his first‑and last‑raid on the Fergussons as the new MacKinnion laird. Dugald had not retaliated after that raid, even though it had cost him twenty head of cattle, seven horses, and nearly one hundred sheep. Dugald knew then he was no match for the MacKinnions, and Jamie knew it, as well.

There was no challenge in carrying on the longstanding feud, so Jamie had let his Aunt Lydia think she had convinced him to end it. It pleased her to think so, and he liked pleasing her. She had always been after him to marry one of Dugald’s four daughters in order to end the feud for good, but he would not go that far. His one marriage had ended so tragically. That was enough for Jamie.

He frowned, thinking how his aunt would react when she learned where he had gone, and of the total destruction his dark side called for. It could very well make her retreat from reality and not return.

Lydia MacKinnion had not been quite right since the MacKinnion‑Fergusson feud had begun forty-seven years before. She had witnessed the cause of it—though she had never told what she saw or said why Niall Fergusson, Dugald’s father, had killed both of Jamie’s grandparents, starting a vicious war that lasted ten years and wiped out half the men of both clans before it settled down to periodic raids that were solely for the lifting of livestock, a practice as common in the Highlands as breathing.

Perhaps Niall Fergusson had been insane. Perhaps insanity ran in their family and Dugald was insane. That was possible. And an insane man must be forgiven, maybe even tolerated. After all, wasn’t his aunt just a little bit insane herself?

A calm settled over Jamie as he came to this conclusion. He could not punish a whole clan for the acts of a madman. His terrible upset about the whole affair was eased then. He would retaliate in kind, but not destroy them all.

The mist was rising steadily as Jamie entered the wooded glen. He saw that he could pass through it in a matter of minutes, the span of trees being no more than a hundred yards. He had ridden only about half a mile away from his men, but with no croft in sight he was beginning to wonder if he was even on Fergusson land, if they hadn’t miscalculated and ridden too far downriver when they sought their crossing.

Then he heard a sound, and in a flash he slid off his horse and ran for cover. But when he listened again, he recognized the sound as a giggle, a feminine giggle.

Leaving his horse behind, he moved stealthily through the bracken and trees toward the sound. At that early hour, the sky was still gray‑pink and mist still clung to the earth.

When Jamie saw her, he wasn’t quite sure he believed the vision. A young girl was standing waist-deep in a small pool, the mist swirling about her head. She looked like a water sprite, a kelpie, unreal, yet real enough.

The girl laughed again as she splashed water across her naked breasts. The sound enchanted Jamie. He was mesmerized by the girl, rooted where he was, watching her play. She was frolicking and having a joyous time of it.

The water should have been freezing. The morning was cold. Yet the girl seemed not to notice the cold. Jamie didn’t, either, after he had watched her awhile longer.

She was like nothing he had ever seen before, a beauty, and no mistake about it. In a moment she faced him, and he saw nearly all of her loveliness. Pearly white skin contrasted starkly with brilliant, deep red hair. Almost magenta, it was so dark and gleaming and long. Two strands waved around her breasts and floated in the water. And those breasts were tantalizing, round, high and proud in youthful glory, the peaks sharply pointed because of the caress of icy water. The tiny waist complemented the narrow shoulders and the taut belly, which dipped teasingly in and out of the water, revealing a gentle swell of hip as the girl moved around. Her features were unmistakably delicate. The only thing not clear to Jamie was the color of her eyes. He was not quite close enough to see, and the reflection of the water made them appear a blue so clear and bright as to be glowing quite impossibly. Was his imagination running wild? He wanted to move closer and see.

What he really wanted was to join her in the water. It was an insane idea, born of the strange effect she was having on him. But if he did move closer, she would either disappear—proving she was not rea

l after all—or scream and run away. But what if she did neither? What if she just stayed there, let him come to her, let him touch her as he ached to do?

Common sense had fled. Jamie was ready to chuck his clothes and slip into the pool when the girl murmured something he couldn’t hear. Suddenly there was a splash, and the girl reached for an object that came from . . . where? Jamie’s eyes widened. Was she truly a sprite then, to invoke something and have it appear?

The object turned out to be a chunk of soap, and the girl began to lather herself with it. The scene was simple enough now, a girl bathing herself in a pool. The unearthly quality was gone, and Jamie’s senses returned. But . . . soap falling into the water all by itself? He scanned the high bank opposite until he saw the man, or, rather, the boy, sitting on a rock with his back to the girl. Her guardian? Hardly. But the boy was watching out for her nonetheless.

Jamie felt the full weight of disappointment descend on him now that he knew he was not alone with the beautiful girl. The presence of the boy brought him back to reality. He had to leave. As if to point out his folly in tarrying, the first rays of sun broke through the glen, showing him the time he had wasted. His brother and the others would have all returned to the men by the river. They would all be waiting for him.

Jamie was suddenly sickened. Watching the girl, being transported to what seemed a sphere outside reality, he was appalled by the contrast between the lovely scene before him and the bloody one he would see in just a short while. Yet he could no more stop the one that was soon to happen than he could forget the one he was watching. Both seemed inevitable.

Jamie’s last look at the girl was a wistful one. Beams of sunlight dotted the pool, and one touched the girl and lit her hair like a burst of flame. With a sigh, he turned away. That last vision of the mystical girl would be etched in his memory for a long time to come.

As he rode back to join his men, Jamie could think only of the girl. Who was she? She could be a Fergusson, some crofter’s daughter, yet Jamie found that hard to believe. What man with such a beautiful daughter would let her bathe as naked as you please in an open pool? And he hated to think she might be a Fergusson. Even a beggar passing through Fergusson land would be preferable.