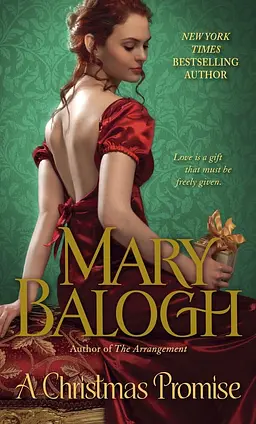

by Mary Balogh

Eleanor, walking back to the house with her aunts and Bessie and Susan, felt cold and alone despite their cheerful chatter. And a little bewildered. Something—a nameless something—had been there within her grasp at the fire. She had leaned back against him and felt his broad shoulder beneath her head and his strong arms about her waist and known quite consciously that she was comfortable, even happy there. Even when she had thought of Wilfred and asked herself if she would be happier in his arms, she had been unable to feel any discontent.

He was her husband and somehow they were going to have to learn to live together. And during the course of the day it had come to seem a less impossible idea than it had at first. It had even begun to be a somewhat attractive idea. There had been that strange, smiling accord between them at the school. There had been his concern over Rachel and his promise to have a word with Sir Albert. There had been that kiss in the snow—her thoughts paused on that memory.

And there had been the fire and his arms and his shoulder and his voice. And the star he had picked out as his. And hers. Theirs. Their Bethlehem star, which was to lead them to hope and peace and love, according to Uncle Ben. She had believed it. Oh, she had been caught up completely in the unreality of the moment. She had believed it, and she had wanted it. With all her soul. With all her heart.

Then his voice again, quite matter-of-fact, telling her that it was a pleasant fantasy. She had been alone a moment later as he had helped put out the fire. She was alone now. Alone with her own foolishness. Only a little more than a month before he had married her, having set eyes on her only once, because he was in desperate need of money to pay off his debts and to enable him to live in the sort of luxury an earl must expect of life. She was of no importance to him. She was merely an encumbrance to him, and an embarrassment too. He had been ashamed of her behavior at the school that afternoon. Her cheeks burned with the humiliation of not having done there what she had been expected to do.

Not that she cared, she told herself. She had never wanted to be a lady. And never ever a countess. He had made her his countess because he had wanted Papa’s money. Well, he had the money. And he had her too. He was just going to have to take her as she was. She would be damned before she would change just to please him.

THERE WAS HOPE. HE kept telling himself that. He had to keep telling himself that. There must be hope. It was just that he must be patient. And not greedy. For he knew that he could never have all that he wanted. He could never touch the Bethlehem star even if it did appear directly over his head and even if he did reach out for it.

She could never love him. Not in the way he now dreamed of being loved. Their marriage had been made under too difficult circumstances. She had not wanted to marry him and had not wanted to enter his world. She loved someone else. No, it was unrealistic to believe that she could come to love him.

But there was hope. There was always hope. Certainly there was something he must tell her. There was a barrier between them and it was largely of his own making since he had considered it unimportant when he first married her to force the truth on her. He had disdained to do so. Now he wanted her to know the truth. It was important to him.

The Earl of Falloden left his bedchamber, tapped on the door leading to his wife’s dressing room, and let himself in. She was there, seated before a looking glass, brushing her hair. It shone like copper.

“I believe our guests are enjoying themselves,” he said, putting his hands on her shoulders as she set the brush down.

“Yes.” She looked at him in the glass. “Even your friends. I think they are lonely gentlemen. Is that why you invited them?”

“I invited them and several others when I was foxed,” he said, and wished he could recall the words even as he was speaking them. He did not add that he had been foxed because he had been unable to see a way out of marrying her. “I suppose these four accepted because they had nowhere else to go. Sotherby lost a wife in childbed two years ago. Did you know?”

“No,” she said softly. She got to her feet and turned from the looking glass. “Poor gentleman. He is a kindly person. I like him.”

She stood before him, making no attempt to move away. His hands reached up almost of their own volition to undo the buttons of her nightgown. She watched his hands. He felt a welling of desire for her. Of need for her. And not just a physical need. A need for her.

Steady, he told himself. Have patience. Don’t ever expect too much of her.

“Eleanor,” he said, opening the last button but pausing before pushing the garment off her shoulders, “I married you because of the money. I must admit that.” Good Lord, he thought, could he have begun with more disastrous words? “But you have misjudged me even so,” he said, rushing on, his voice stilted. He should have rehearsed this speech, got it just right before opening his mouth.

“Have I?” She raised her eyes to his. “Don’t remind me of it. Please? Not at this moment. You want me in bed?”

“I am not a gamer,” he said, “or unduly extravagant. Those debts were not mine.”

“Oh, please,” she said, as she lifted her hands and pushed her nightgown off her shoulders herself and shook it down her arms and over her breasts until it fell to her feet. She closed her eyes and walked against him. “I don’t want to hear it. It does not matter. You are my husband and I have accepted that. Have I not? Did I not submit myself to you last night? Did I not please you?”

Acceptance. Submission. Her naked body pressed to his, her eyes closed submissively. Because she was his wife. Because she had agreed to marry him to please her father and would honor that commitment for the rest of her life. Duty and honor. She had no interest in hearing any explanations.

He turned a little cold. And yet he could feel her soft, warm curves against him, his nightshirt the only barrier between them. He could see her breasts pressed against his chest and her dark red hair in shimmering waves over her shoulders and along her back. He desired her. He desired his wife and she would submit herself to him.

It was his heart that was cold. His body was on fire.

“I thought perhaps,” he said, “you might be interested in knowing me. That perhaps we might learn to be friends.”

“You want me in bed,” she said, and her voice was as chilly as his heart. “Shall I go there?”

“Yes,” he said, and he watched her walk through to the other room and lie down on the bed as he pulled off his nightshirt and dropped it to the floor with her nightgown.

He desired her, he thought as he looked down at her on the bed a few moments later, lying submissively on her back. He could feel the blood pulsing through him, and he needed to be in her. He needed to work toward release. He pushed her legs wide, knelt between them, positioned himself, and pushed inward. She was hot and wet. She wanted him too, then, for all the stillness of her body and the calmness of her face. They desired each other. He lowered his body onto hers and began to move swiftly and deeply.

And yet it was not the way he had wished it. His body worked feverishly toward its satisfaction while his mind remained strangely aloof. This was purely physical, he thought, wonderful as it was. This was merely his body taking pleasure from hers. The mere planting of his seed for her pleasure.

There should be something else. He wanted something else. He wanted to join their mouths as well as that other part of their bodies. He wanted to be able to look into her eyes and see her soul. He wanted her to gaze into his. He wanted words, words spoken and words heard. He wanted the Bethlehem star, he realized. And he knew that his own resolve to be content with less might not be enough.

He wanted her. Oh, God, he wanted her. Like this. Yes, like this and like this and like this. But more than this. He wanted more.

“Ah.” He tensed in her and turned his face to sigh against the side of her head. And then he felt all the blessed relief of tension as he spilled into her. She lay still and quiet and soft and warm beneath him.

They were two very separate entities, he thought

when thought returned to him. Two very different worlds. Joined in body as intimately as man could be joined to woman. His seed was in her, perhaps even the beginnings of their child. But worlds and universes apart. He uncoupled them with an ache of regret and moved to her side. Fantasy, he had called his feelings at the fire when he had wanted to defend himself against her silence. He had spoken the simple truth. It had all been fantasy.

He should go back to his own room, he thought. She had done her duty. Now he should give her rest. Tomorrow would be busy enough. And if he stayed, he would desire her again during the night. He should go.

He fell asleep.

And woke up some time later, a long time later—both the fire and the candles had burned themselves out. She was burrowing against him and muttering and searching for his mouth with her own. He knew she was still asleep even as he came awake and gave her what she sought. He kissed her hungrily with lips and teeth and tongue and wondered as she gradually woke up who it was she had been dreaming of. She was hot for whoever it was. Her breasts, he found when he pressed a palm against one, were tautly peaked.

But he would not think of the identity of her dream lover. He lifted her, warm and still sleepy, on top of him and drew her legs apart with his hands, bringing her knees up to hug his waist. And he lifted her by the hips and entered her as he brought her back down. He found her mouth again and loved her hotly and fiercely, as he had dreamed of loving her. And exulted in the growing heat of her and in the way she rode to his rhythm and tightened her muscles about him at the end until she cried out with him and shuddered down onto him as he drew the blankets up about her.

As she had done on their wedding night, he recalled. Except that there was a difference. Oh, there surely was a difference. She had been with him this time. All the way. Every step of the way.

“Eleanor,” he whispered against her ear.

But she was asleep again.

Eleanor. My wife. My lover.

My love.

He resisted sleep for a while. He was too warm and comfortable and relaxed not to want to enjoy the sensations. And she was soft and warm on him. They were still joined.

My love. It was a wonderful dream. A Christmas dream. Perhaps reality would seem very cold in the morning. He wanted to stay awake and hold on to the dream.

He slept again.

13

SIR ALBERT HAGLEY WAS IN THE BILLIARD ROOM with Lord Charles, Aubrey Ellis, Wilfred, and Uncle Harry. The earl wandered in and watched for a while.

“Ouch!” he said quietly when Lord Charles, after making a couple of shots bordering on brilliance, missed an easy pocket. “A stroll in the long gallery, Bertie?”

Sir Albert opened his mouth to protest, looked into his host’s face, and set his cue against the wall. “Why not?” he said. “It is too miserable to be outside. Snow and blowing snow—not at all kind Christmas Eve weather.”

“It will clear by noon,” Uncle Harry said cheerfully as the two men left the room.

“None of the ladies is strolling in the gallery,” the earl said. “The lure of the fire in the morning room must be too tempting. We will have the gallery to ourselves.”

“And is that important?” Sir Albert asked, looking curiously at his friend. “That we be alone, I mean?”

The earl did not answer. But he closed the door firmly behind him as they entered the gallery.

“Ugh!” Sir Albert said, strolling toward the nearest of the long windows that ran the length of one side of the room. “I hope Gullis is right about this clearing by noon. One hates to be housebound on Christmas Eve.”

“What are your intentions toward Rachel Transome?” the earl asked quietly.

Sir Albert looked around in surprise. “My intentions?” he asked. “Good Lord, Randolph, you are not playing heavy-handed head of the family, are you? You aren’t the head of the family. I imagine the butcher is—Uncle Sam.”

“You have been paying her a great deal of attention,” the earl said. “You were seen among the trees last night kissing her.”

“I would have been a damned slowtop if I had missed the opportunity,” Sir Albert said. “Have you had a good look at the girl? Or spent any time talking with her?”

“She is an innocent,” the earl said. “She is not up to your experience, Bertie. And she is an innkeeper’s daughter.”

Sir Albert shrugged. “Well, your wife is a coal merchant’s daughter,” he said. “She appears to be fitting rather well into the role of countess. Are you warning me off, Randolph? I don’t quite understand what this is all about.”

“I know your feelings about cits,” the earl said.

Sir Albert stared at him. “It was not so many weeks ago that you were damned deep in your cups because you were being trapped into marrying one,” he said. “Do you have such bitter regrets that you want to save me from making the same mistake? Do you find this family quite impossibly vulgar?”

“Rather the contrary,” the earl said. “I envy their exuberance and warmth and the affection they all seem to feel for one another. There have been moments when I have longed to be one of their number—and then I have remembered that I already am, as Eleanor’s husband.”

“Devil take it.” Sir Albert looked at his friend with interest. “You are growing fond of her, Randolph.”

But the earl’s posture was stiff, his face unsmiling. “She told me that you tried to seduce her at Hutchins’s two summers ago,” he said.

“Did she? So you know that it was her, then,” Sir Albert said. “I am not sure that seduction is quite the word, though, Randolph. I tried to take liberties, I suppose—see how far I could go. It was not very far at all.”

“Because she was a cit.” The earl’s voice was hard. “You would not have treated Hutchins’s daughter so, Bertie.”

Sir Albert was frowning again. “Am I to answer for something that happened two years ago?” he asked. “Or rather, for something that did not happen?”

“I don’t want it repeated with Rachel,” the earl said. “That’s all, Bertie. She is my wife’s cousin and my guest here. As far as anyone else is concerned, she is a lady and to be treated as such.”

“I would have kissed her last night if she had been ten times a lady,” Sir Albert said. “I am infatuated with her, if you must know, Randolph. Perhaps more. She has a deal more sense than most of the butterflies one meets in London ballrooms. And oceans more beauty. And I still maintain I am not answerable to you. I will answer to her father if I must.”

“Will you?” The earl looked instantly relieved. “You mean honorably, then, Bertie? Why did you say that Eleanor was vulgar?”

“I did not—”

“Yes, you did,” the earl said. “When you thought she might be the one who had been at Hutchins’s. When I first talked of marrying her.”

“She was vulgar,” Sir Albert said. “Cockney accent that might have been cut with a knife. And loud, Randolph. And a laugh straight from the gutter.”

“Ah,” the earl said. “And was that before or after the attempted seduction, Bertie?”

“I did not notice it before,” Sir Albert said, “or I doubt I would have wanted to get close to her.”

The earl nodded. “Ah, yes,” he said, “Eleanor would do that. I can almost picture it. Fists clenched, figuratively speaking, sleeves rolled to the elbows, and eyes flashing.”

“I have been having a hard time believing that she is the same woman, as a matter of fact,” Sir Albert said. “But listen, Randolph. I like this family. Who would not? They are making a rather cheerful time out of Christmas, aren’t they? I have almost forgotten that I came here to shoot.”

“And you’ll not harm Rachel?” the earl asked.

Sir Albert looked at him somewhat uneasily. “I have tried staying away from her,” he said. “At first, I suppose, because she is the daughter of an innkeeper and Mama would have a fit if I brought her up for inspection. Later because I did not want to find myself trapped in an impossible situation

, with her whole family looking on and all that. I never did entertain the thought of seduction, Randolph. Good Lord, what do you think of me?”

“That you know how to behave,” the earl said. “But Eleanor was agitated. You really feel a fondness for the girl, Bertie?”

“Mama would have a fit,” Sir Albert said.

“But you would be the one to have to live with the girl,” the earl said.

“And so I would.” Sir Albert scratched his head. “Devil take it, it’s quite a thought, isn’t it? I had better stay away from her for the rest of today.”

“If you can,” the earl said. “I suppose you will discover the depth of your feeling in the course of the day.”

“Lord,” Sir Albert said. “An innkeeper’s daughter. And a coal merchant’s daughter. Does it matter, Randolph? I mean, does it really matter?”

“To me it does not,” the earl said. “And I had better go and see if Eleanor wants any help in the ballroom. She has decided that it should be decorated for the children’s concert and party this afternoon.”

“I’ll go back to the billiard room,” Sir Albert said. But his friend did not step aside from the door when he approached. He stood and looked at him broodingly instead. Sir Albert raised his eyebrows.

“I’m sorry, Bertie,” the earl said, “but I have to do this. It is for my wife.”

And the next moment Sir Albert’s expression turned first to surprise and then to pain as a fist connected sharply with his jaw. He staggered backward, stepped awkwardly, and went sprawling on the floor.

“If you want to make something of it,” the earl said, “you can slap a glove in my face, Bertie. I’m sure we can both find seconds here and settle the matter well away from the house and the ladies.”

Sir Albert flexed his jaw and felt it gingerly with the tips of two fingers. He frowned up from his sitting position on the floor.

“Growing fond of her!” he said in disgust. “You’re bloody in love with her, Randolph. That’s the first time—and the last, I hope—that I have been punished for a two-year-old crime.”